The United States formally recognized the Republic of Texas on March 3, 1837, just over a year after Texas declared its independence from Mexico. This recognition came at the end of Andrew Jackson’s presidency and reflected both strategic interest and personal rapport.

Texas President Sam Houston had long maintained close ties with Jackson, having served under him during the War of 1812 and maintaining a mentor-mentee relationship. Jackson saw in Houston a capable frontier leader, and their friendship helped lay the diplomatic groundwork for Texas’s push for international legitimacy.

Jackson’s recognition of Texas was cautious but deliberate. He waited until after the U.S. presidential election of 1836 to avoid inflaming sectional tensions over slavery and expansion. The recognition came as one of Jackson’s final official acts—one day before he left office—signaling his personal support for Texas’s independence while stopping short of any commitment to annexation.

Houston, aware of Jackson’s political instincts, timed Texas’s overtures accordingly. With recognition secured, Texas could begin formal relations with the United States and other countries—critical steps for the fledgling republic’s survival.

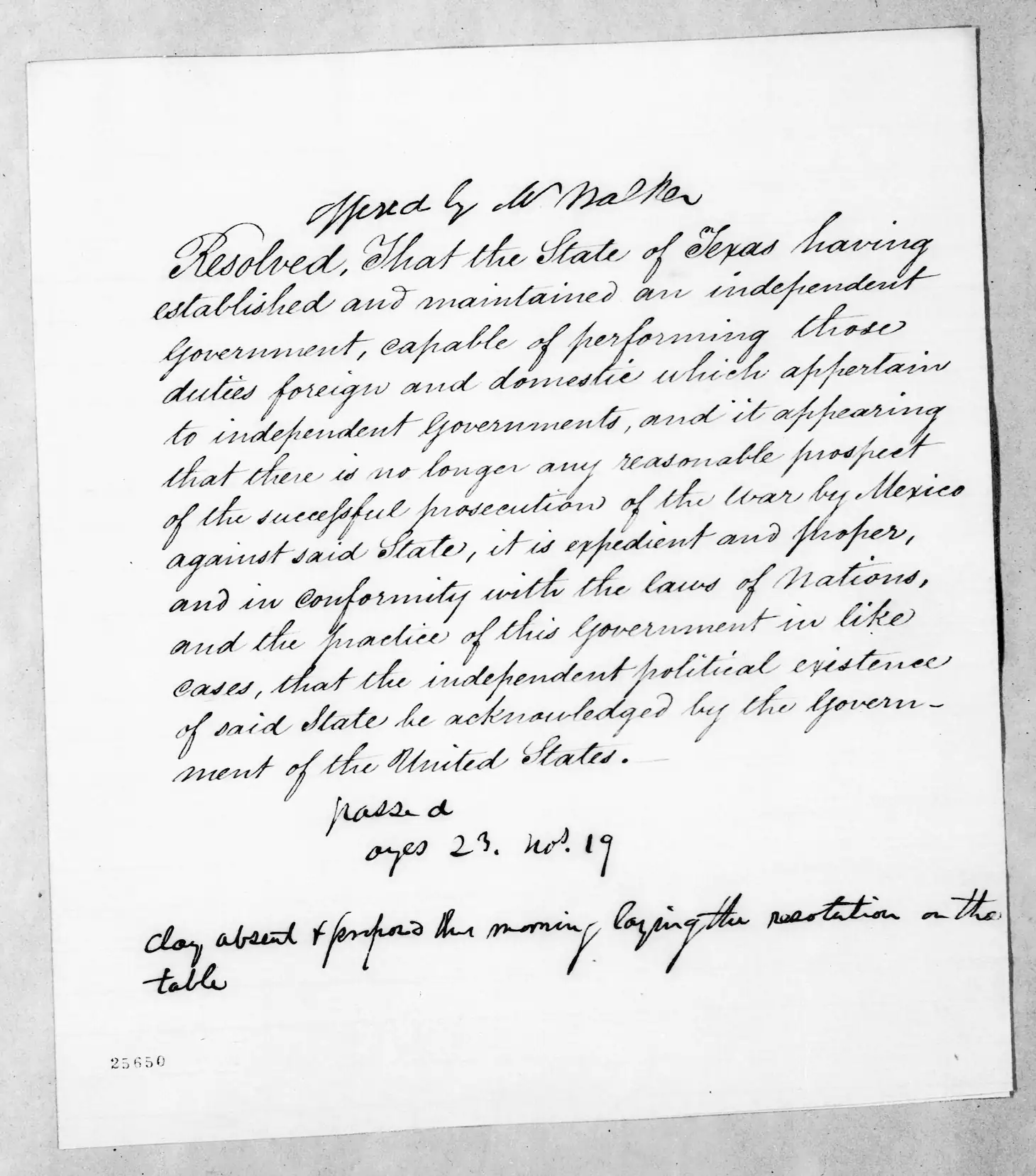

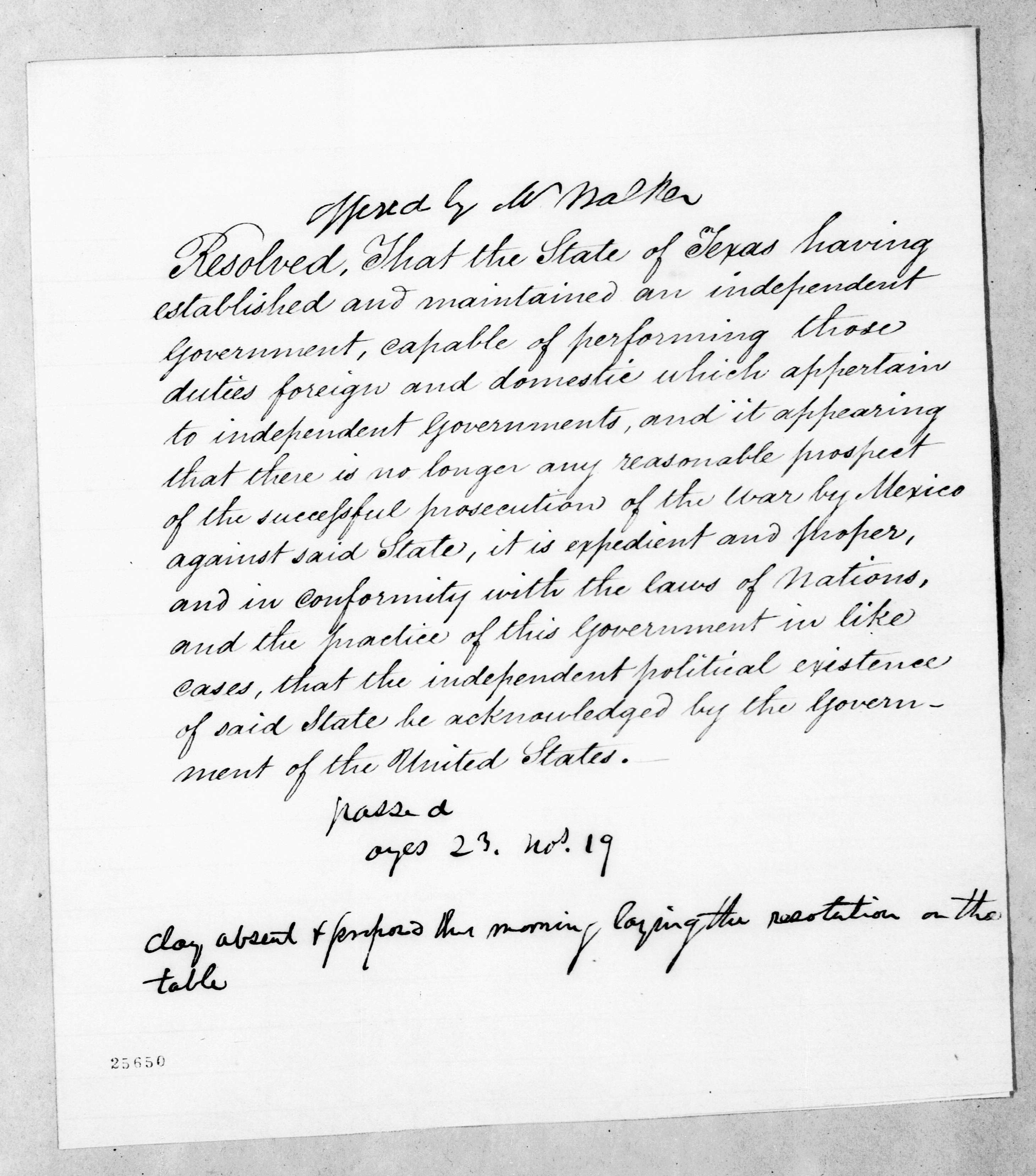

Recognition took the form of the appointment of a Chargé d’Affaires to the U.S. Legation in Houston, then functioning as the seat of Texas government, on March 3rd, 1837. On the same date, the U.S. Senate approved a resolution to recognize “the independent political existence” of Texas, by a vote of 23 to 19.

The below handwritten note, found in the papers of U.S. President Andrew Jackson, details the resolution text and the vote outcome in the U.S. Senate. It may have been given to him by a messenger or aide tasked with observing the senate proceedings.

The resolution stated,

“Resolved, That the State of Texas having established and maintained an independent Government, capable of performing those duties foreign and domestic which appertain to independent Governments, and it appearing that there is no longer any reasonable prospect of the successful prosecution of the war by Mexico against said State, it is expedient and proper, and in conformity with the laws of nations, and the practice of this Government in like cases, that the independent political existence of said State be acknowledged by the Government of the United States.”

U.S. recognition of the Republic of Texas was a pivotal moment in 19th-century diplomacy because it signaled to the international community that Texas was not merely a rebellious province of Mexico but a sovereign nation worthy of formal relations.

At a time when European powers, particularly Britain and France, were watching developments in the Americas with interest, the U.S. endorsement gave Texas a degree of legitimacy that made further recognition more likely.

The move also heightened U.S. tensions with Mexico, which refused to acknowledge Texas’s independence and viewed American recognition as interference in its internal affairs. By recognizing Texas, the United States asserted its influence in the Western Hemisphere and reinforced the Monroe Doctrine’s spirit—discouraging European intervention in the region while expanding its own diplomatic and territorial ambitions.

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.