Overview

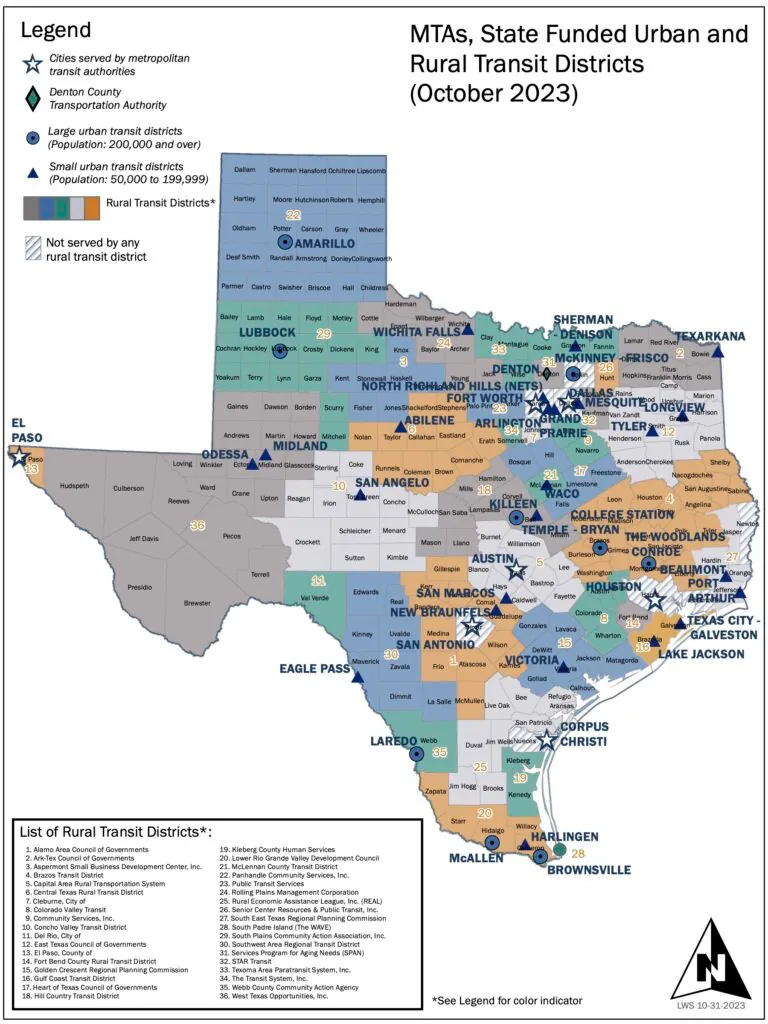

The State of Texas has no statewide public transit system or statewide strategy but relies on three types of local government entities to provide services: rural transit districts, urban transit districts, and metropolitan transit authorities, or MTAs. Additionally, 58 Texas public entities offer limited service specifically for seniors and those with disabilities.

Fixed-route buses typically operate in larger towns or on key regional routes, offering scheduled service along designated paths. However, in more remote areas, demand-response services are often the primary option, providing flexible, on-call rides for individuals who cannot access scheduled bus routes. Vanpooling and carpooling programs are also common, especially for commuters who travel to neighboring towns or cities for work.

Train services are less common but are available in specific larger transit systems.

Rural Transit Districts

Texas’ 36 rural transit districts serve areas with fewer than 50,000 residents. These districts typically offer a combination of fixed-route bus services and demand-response transit (often referred to as dial-a-ride).

The largest rural transit districts by ridership are located in El Paso County, Fort Bend County, and South Padre Island. These areas have seen significant increases in population and demand for transit services in recent years, contributing to their large ridership numbers. These districts help bridge the gap between rural and urban transportation needs, ensuring that residents can access healthcare, education, and employment opportunities with greater ease.

Urban Transit Districts

An urban transit district in Texas typically operates within a “small urbanized area” with a population between 50,000 and 199,999. Texas is home to 21 such districts, which provide essential services to mid-sized urban areas. In addition, another 10 districts qualify for state funding under specific statutory exceptions, even though they serve areas with populations greater than 200,000.

One standout example is Bryan-College Station, which is operated by the Brazos Transit District. In fiscal year 2019, Bryan-College Station reported 6.7 million passenger trips and $10.8 million in operating expenses, making it the largest urban district by ridership.

Metropolitan Transit Authorities

The metropolitan transit authorities (MTAs) in Texas are responsible for providing transit services in areas with populations exceeding 200,000. These authorities are unique in their ability to levy local sales taxes to fund their operations, making them financially robust and capable of delivering a wide range of services.

Subtypes in this category include metropolitan rapid transit authorities (in Houston, San Antonio, Austin and Corpus Christi), regional transportation authorities (Dallas and Fort Worth), municipal transit departments (El Paso) and the Denton County Transportation Authority, a joint venture between Denton County and the cities of Denton and Lewisville.

Given the number of people they serve, MTA budgets are much larger than those of the smaller transit agencies. Harris County’s MTA, Houston Metro, delivered more than 90 million passenger trips with $575 million in operating costs in fiscal 2019, followed by Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) at nearly 63 million trips and $987 million in expenses.

This web of agencies and the relationships among them can be complex. Some rural transit districts are becoming urbanized, and some provide services in overlapping urban districts or in partnership with neighboring entities. In the Dallas-Fort Worth area, state law allows four urban districts to operate (and thus to receive state funding) within the DART service area.

Mass Transit Funding

Texas’ transit programs rely on a blend of federal, state, and local funding, with farebox revenue contributing only a modest share of total operating costs. In most systems, fares cover less than 20% of expenses, reflecting the public service nature of transit and the need for external subsidies to maintain accessibility and coverage.

All Texas transit agencies are eligible to receive federal funding, primarily through the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and, in some cases, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). These funds are distributed through programs such as Section 5307 for urbanized areas, Section 5311 for rural transit, and capital investment grants for major infrastructure projects. Federal support plays a crucial role in sustaining both day-to-day operations and long-term capital planning.

At the state level, funding is managed by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) through the Public Transportation Division. State appropriations help support both rural and urban transit providers, though the overall amount is modest compared to other large states. TxDOT also acts as a conduit for certain federal programs, particularly in rural areas that lack the administrative capacity to manage grants directly.

Local funding varies widely depending on the governance model of the transit agency. Most urban transit authorities in Texas—such as DART, Houston METRO, and VIA Metropolitan Transit—are supported by a dedicated local sales tax, typically capped at 1% and approved by voters. Some systems supplement these funds with general municipal revenues or service contracts. A notable exception is Austin’s Project Connect, which receives additional support through a dedicated property tax rate, approved by voters in 2020 to finance major light rail and transit infrastructure.

Transit Networks and Cooperation

Texas’ public transit landscape is decentralized but functionally collaborative, with local and regional transit authorities managing service delivery across a wide range of geographies. In urban areas like Dallas–Fort Worth, multiple transit agencies—including DART, Trinity Metro, and smaller municipal systems—operate within overlapping zones under state law, often coordinating services and sharing facilities. Similar cooperative arrangements exist between rural and suburban districts, especially in transitional areas where population growth has blurred traditional jurisdictional lines. These interagency partnerships allow transit systems to meet rider needs across district boundaries without requiring a centralized governing body.

Still, the state lacks a unifying transit strategy or long-range planning framework. There is no single state agency charged with guiding public transportation development across regions, and dedicated state funding is relatively limited. As a result, system expansion, capital investment, and infrastructure planning depend largely on local voter initiatives, federal grants, and interlocal agreements. While this structure allows flexibility and local control, it may also limit opportunities for coordinated investment and long-range transit development.