In the landmark case Texas v. White, decided in 1869, the United States Supreme Court ruled that states could not unilaterally secede from the Union, affirming the perpetual nature of American federalism and reshaping the legal understanding of state sovereignty in the aftermath of the Civil War. The case arose from a financial dispute involving bonds but soon developed into a constitutional reckoning over the legitimacy of Texas’s Confederate-era government and the broader meaning of Union.

Case Background

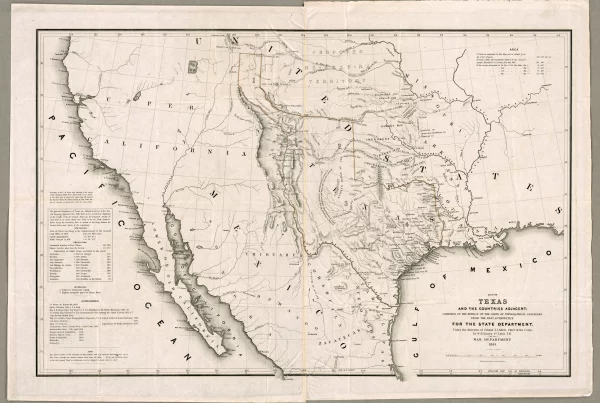

The case began with a seemingly technical legal matter. During the final months of the Civil War, the Confederate government of Texas transferred U.S. Treasury bonds—originally issued to the state a decade earlier—to private merchants George White and John Chiles in exchange for medicine and supplies. These men had effectively loaned money to the Confederacy, betting that they could redeem the bonds later for full value.

After the war, they tried to collect. But the U.S. Treasury refused to pay, arguing that the transaction was unauthorized and that anyone who had supported the rebellion must bear the financial consequences. Texas’s new Union-backed government sued to block payment altogether, claiming the bond transfers were invalid and the Confederate regime had no legal authority to dispose of them.

The lawsuit targeted private parties like White and Chiles, who had acquired the bonds during the war and, in some cases, redeemed them after the Confederacy had collapsed. The Reconstruction government of Texas asked the Supreme Court to declare the wartime transfers void and to compel the return of the bonds—so that Texas, now reestablished under federal authority, could redeem them through proper channels and use the funds for postwar recovery.

To resolve the dispute, the Supreme Court had to answer much more than a financial question. Was Texas still a state during the rebellion? Could its Confederate government enter into binding legal agreements? And most importantly—could any state legally leave the Union in the first place?

The Constitutional Questions at Stake

The technical question before the Court was whether the bonds had been validly transferred. But more fundamentally, the case raised sweeping questions:

- Did the acts of a Confederate state government carry legal weight?

- When did Texas cease to be a state of the Union—if at all?

- If Texas had ceased to be a state, how could it rejoin the Union?

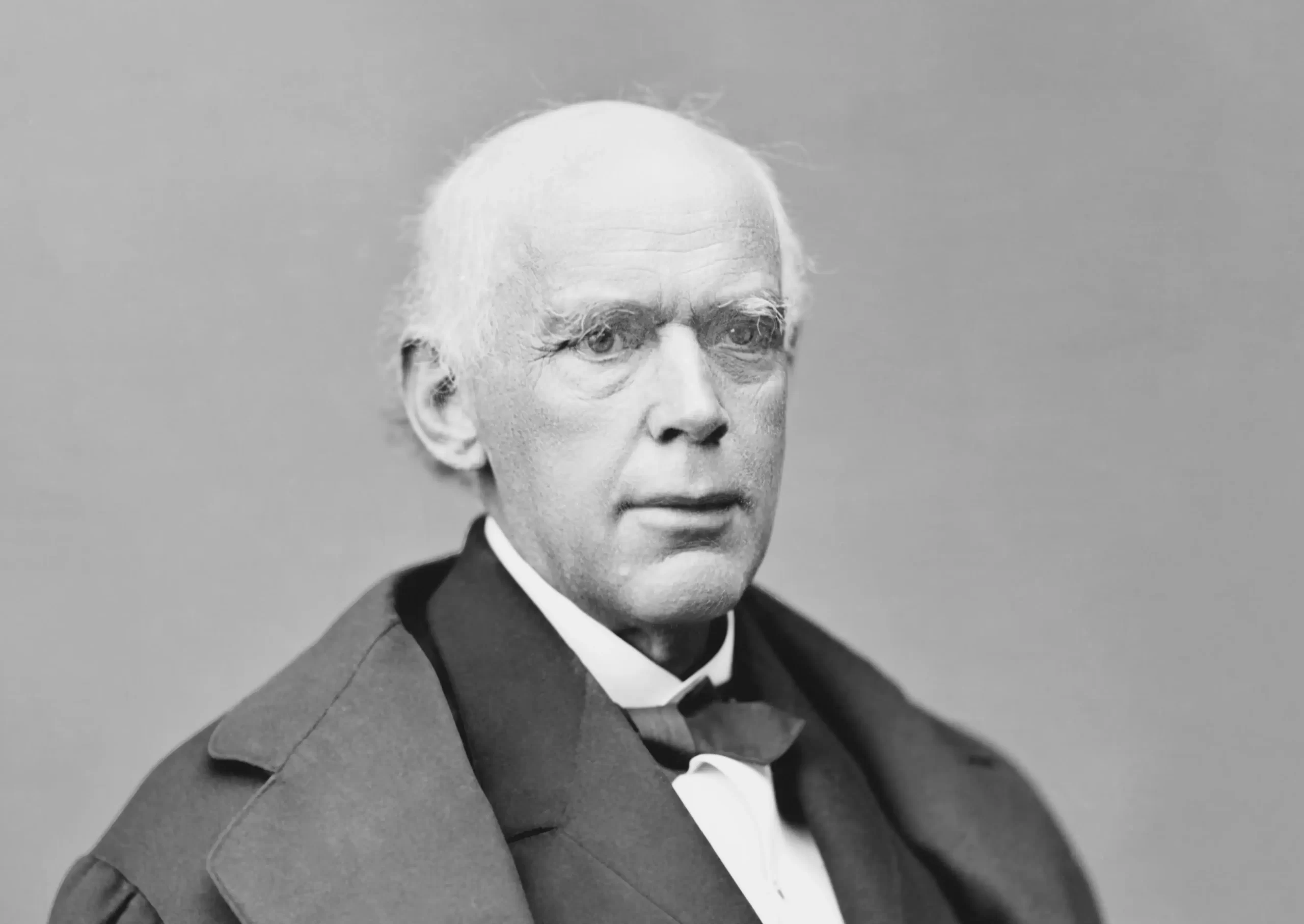

The U.S. Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase—a former Treasury Secretary under Lincoln—used the opportunity to define the constitutional nature of the Union itself. He wrote, “If it is true that the State of Texas was not, at the time of filing this bill, or is not now, one of the United States, we have no jurisdiction of this suit, and it is our duty to dismiss it. We are very sensible of the magnitude and importance of this question.”

The Court’s Decision

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Chase (pictured, top) concluded that Texas had remained a state throughout the Civil War, despite its attempt to secede. The Court declared that the Union was “perpetual” and “indissoluble,” and that individual states had no legal right to withdraw unilaterally. Because Texas had never ceased to be a state, it retained standing to sue in the Supreme Court—and its Reconstruction-era government was entitled to reclaim state property transferred without lawful authority.

The Court held that, although Texas had never ceased to be a state, its Confederate government lacked lawful authority. Chief Justice Chase distinguished between the state’s continued conceptual legal existence within the Union and the illegitimate regime that had taken power during the rebellion. Secession, he argued, was constitutionally void from the outset; but those who governed in defiance of the Union could not enter into binding legal agreements on the state’s behalf.

This distinction allowed the Court to uphold Texas’s standing while declaring the wartime bond transfers invalid. Because the Confederate authorities lacked legal capacity to dispose of public assets, the bonds remained state property. The Reconstruction government, as the lawful successor, was entitled to reclaim them or recover any proceeds obtained through unauthorized redemption.

In practice, the Court enjoined further payment on the disputed bonds and ordered their return—but questions about already-redeemed bonds were left for lower courts or future proceedings to resolve. The ruling preserved Texas’s financial interests while leaving open the practical challenges of enforcement.

Dissent and Partial Concurrence

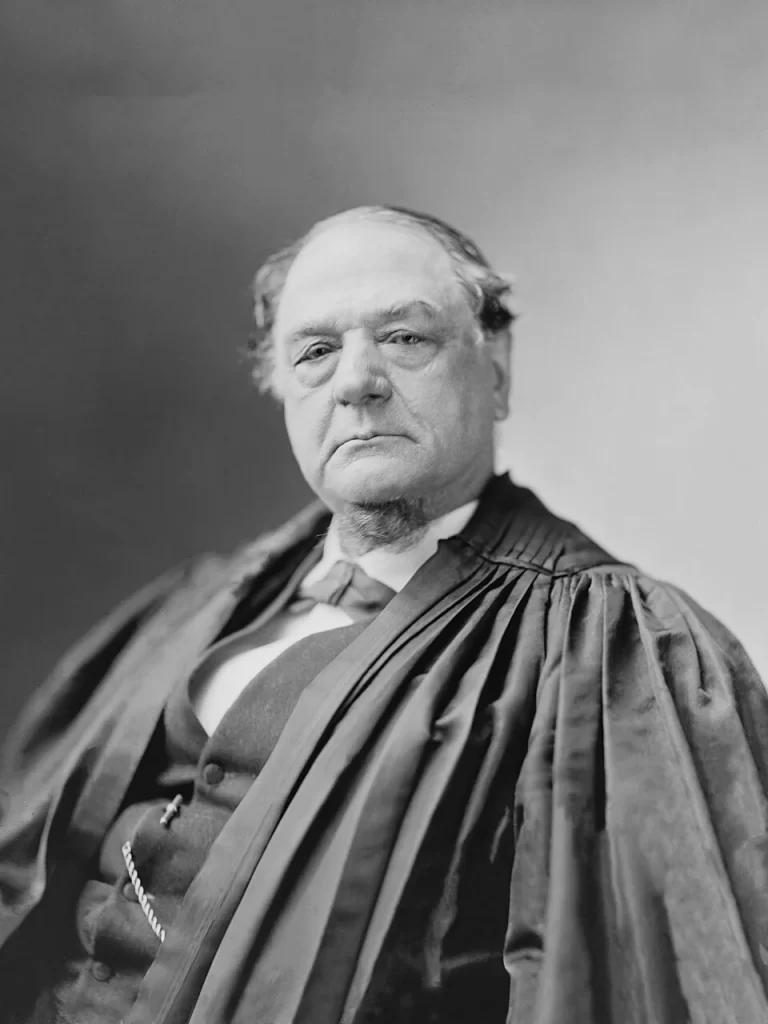

Justice Robert Grier filed the sole full dissent, arguing that Texas, having seceded and fought against the Union, could not now assert rights in the Supreme Court as if nothing had changed. In his view, Texas had ceased to function as a state in the constitutional sense and lacked standing to sue. He agreed that the bonds should not be repaid—but not because the wartime transfers were invalid, as the majority held. Rather, Grier’s reasoning was rooted in the idea that a state in rebellion could not expect legal protection or financial recovery from the Union it had renounced.

Justices Noah Swayne and Samuel Miller dissented only in part. While they agreed with the majority that the Confederate-era bond transactions were invalid and supported the relief ordered, they argued that the case should have been dismissed for lack of standing. In their view, Texas could not appear before the Supreme Court because it had seceded and ceased to function as a state within the Union.

To hear the case at all, they contended, improperly legitimized the current state government and assumed Texas’s continuing statehood. They asserted that readmission to the Union could only occur through congressional action.

The partial dissents revealed a conflict about who had the authority to restore former Confederate states. On one side was the Court, recognizing Texas’s continued legal existence; on the other was Congress, which insisted on setting the terms for readmission and representation.

Significance for Texas and the Nation

Texas v. White implicitly challenged aspects of Congressional Reconstruction, which had treated the Southern states as having forfeited normal constitutional status. In response, Congress doubled down on its authority—maintaining military rule in the South and requiring former Confederate states to adopt new constitutions and ratify the Fourteenth Amendment before regaining representation in Congress and ending federal occupation.

In the short term, the ruling strengthened the legal framework for Reconstruction by affirming the authority of federal officials and Union-backed state governments to void Confederate-era contracts and reorganize institutions that had supported the rebellion. In the longer view, however, the Court’s declaration of the Union’s permanence reinforced the idea that the former Confederate states had never truly left—and thereby it may have helped hasten the reintegration and the eventual end of Reconstruction.

To this day, Texas v. White stands as the primary judicial precedent against secession in the United States. The ruling is often cited in discussions of national unity, federal supremacy, and the legal status of states. Although movements for state sovereignty or “Texit” occasionally resurface in Texas politics, the Court’s 1869 opinion leaves little constitutional room for such claims.

Full Text of Texas v. White

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.