This page presents key excerpts from the 1893 Texas public school law and a 1895 law amending it. These documents show how Texas transitioned from informal racial separation in public education to a fully codified system of segregation. They reflect the broader transformation of the post-Reconstruction South, as White lawmakers worked to formalize racial boundaries in law through what would become known as the Jim Crow system.

The 1893 law, passed as Chapter 122 of the General Laws of the 23rd Legislature, defined the structure of public schooling statewide—establishing school districts, funding rules, trustee responsibilities, and, critically, racial boundaries. The law stated,

“White and colored children shall not be taught in the same schools, but impartial provision shall be made for both races.”

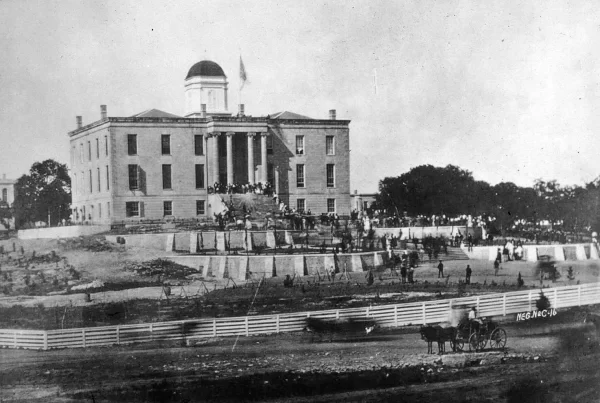

Prior to 1893, Texas had not explicitly segregated schools by law, though they were often—if not almost always—racially separate in practice. Black Texans had organized their own schools after being freed from slavery in 1865, with the support of the federal Freedmen’s Bureau. Meanwhile, White Texans continued to send their children to the existing schools, and resisted integration at every level.

Segregation was thus widespread by custom long before it was written into law. Even so, the 1893 law implied the existence of some mixed schools at the time. It referred to “any school consisting partly of white and partly of colored children.” It prohibited the disbursement of state funds to these schools, signaling a willingness to use state powers to curtail mixed schooling, even in the few communities where it had emerged organically.

The 1893 law provided for the election or appointment of separate trustees for the management of schools—three white, and three colored. Notably, the law codified the subordinate position of the colored trustees. It stated:

“[The] colored trustees shall manage the colored schools, under the direction of the [white] trustees of the district.”

Perhaps anticipating legal challenge, the Legislature modified this in 1895, placing the two boards on nominally equal footing, albeit under the supervision of a county superintendent, who was likely to be White (since very few state or local officials at the time were Black). Blacks thus were given a degree of autonomy in managing the affairs of their children’s schools, but depended on the all-White county governments of the time for funding.

Both the 1893 law and its 1895 amendment insisted that “impartial provision shall be made for both races,” echoing the logic that would soon be affirmed in the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson—that racial separation could be fair if applied equally.

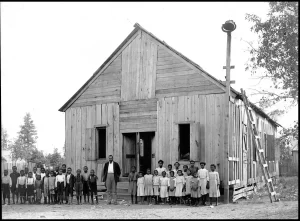

But in practice, Texas’s “colored schools” were consistently underfunded, overcrowded, and lacking in basic learning materials. Black teachers were paid less, school terms were shorter, and school buildings were often dilapidated. The promise of “impartial provision” served to legitimize racial segregation while shielding the state from accountability for the stark disparities it maintained. It wasn’t until 1954 that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned this, declaring that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

General Laws of Texas — Public Free Schools

23rd Legislature, Regular Session (1893)

Chapter 122 — [Substitute House Bill Nos. 30, 115, et al.] An act to provide for a more efficient system of public free schools for the State of Texas… providing for the creation of school districts in all the counties of this State; providing for the levy and collection of special taxes for the further maintenance of the public free schools….

Sec. 10. No part of the public school fund shall be appropriated to or used for the support of any sectarian school.

Sec. 11. All available public school funds of this State shall be appropriated in each county for the education alike of white and colored children, and impartial provisions shall be made for both races.

Sec. 12. All children, without regard to color, over eight years of age and under seventeen years of age, at the beginning of any scholastic year, shall be entitled to the benefit of the public school fund for that year.

Sec. 13. The scholastic year shall commence on the first day of September of each year and end on the thirty-first day of August thereafter.

Sec. 14. The children of the white and colored races shall be taught in separate schools, and in no case shall any school consisting partly of white and partly of colored children receive any aid from the public school fund.

Sec. 15. The terms “colored race” and “colored children,” as used in the preceding section, and elsewhere in this act, include all persons of mixed blood descended from negro ancestry.

… Sec. 58. White and colored children shall not be taught in the same schools, but impartial provision shall be made for both races. Three white trustees shall in all cases be elected, or appointed, for the management and control of the schools of the district; and three colored trustees shall be elected, or appointed, in any school district for the colored schools therein, upon the written application of ten colored residents of said district, having one or more children within the scholastic age, to the county superintendent one month before any annual election in said district for school trustees, which colored trustees shall manage the colored schools, under the direction of the trustees of the district. In case there are not enough colored children in any school district, as laid off, then two or more of said districts may be consolidated by the trustees for the benefit of the colored school, and each of the districts shall pay pro rata, according to colored scholastic census in each, from the district school fund for its support, and shall be governed by the trustees of the district in which the school is taught.

… Sec. 94. Every child in this State of scholastic age shall be permitted to attend the free public schools of the district or independent district in which it resides at the time it applies for admission, notwithstanding that it may have been enumerated elsewhere, or may have attended school elsewhere part of the year: Provided, that white children shall not attend the schools supported for colored children, nor shall colored children attend the schools supported for white children…

Approved May 20, A.D. 1893.

General Laws of Texas — Public Free Schools

24th Legislature, Regular Session (1895)

CHAPTER 24 — [Committee Substitute for House Bill Nos. 3 and 7]: An act to amend section 58 of chapter 122 of the general laws enacted by the Twenty-third Legislature, entitled “An act to provide for a more efficient system of public free schools for the State of Texas; defining the school funds,” etc., approved May 20, 1893; to provide for separate boards of trustees for the white and colored schools of each school district; to provide for the maintenance of separate schools for white and colored children of each district; to provide for the apportionment of the school funds of each district to the respective schools thereof.

Section 1. Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Texas: That section 58 of said act be amended so that hereafter it shall read as follows:

Section 58. White and colored children shall not be taught in the same schools, but impartial provision shall be made for both races. Three white trustees shall in all cases be elected for the control and management of the white schools of the district, and three colored trustees shall be elected for the control and management of the schools for colored children.

The election for white and colored trustees shall be held at the same times and places, and the ballots cast for white trustees shall be deposited in a separate box from that used for the ballots cast for colored trustees. The returns of the election shall be made to the county judge, who shall deliver the same to the commissioners court to be canvassed and the result declared as in cases of other county elections. The returns shall show distinctly the separate votes for white and colored trustees, and the county clerk shall certify to the county superintendent the white and colored trustees elected for each district, and the county superintendent shall issue the commissions of trustees.

Each year after the scholastic census of the county is completed, the county superintendent shall, if any district has less than twenty pupils of scholastic age, either white or colored, have authority to consolidate said district as to said white or colored schools with other adjoining districts, and to designate the board of trustees which shall control the white or colored school of such consolidated district. But this shall be done before the apportionment is made, and the apportionment shall be made with respect to such consolidation.

The white trustees of each district shall be the trustees of the district for all purposes having relation to the management or control of the white schools, and the fund apportioned for their support, and the colored trustees shall be the trustees for all purposes in reference to the management or control of the colored schools and the funds apportioned for their support.

The apportionment to the white and colored schools of each district shall be made in the following manner: The county superintendent, upon the receipt of the certificate issued by the Board of Education for the State fund belonging to his county, shall apportion the same to the several school districts (not including the independent school districts of the county), making a pro rata distribution as per the scholastic census, and shall at the same time apportion the income arising from the county school funds to all the school districts, including the independent school districts of the county, making a pro rata distribution as per scholastic census.

Within thirty days after said apportionment is made by the county superintendent of education, the white and colored boards of trustees of such district shall, if possible, agree upon a division of the funds of the district between the white and colored schools, and shall fix the term for which the schools of the district shall be maintained for the year.

Should they agree upon a division of the funds of the district or upon the length of the term for which the schools of the district shall be maintained, they shall at once certify their agreement to the county superintendent, who shall not approve any contract with teachers of the district until said agreement is received.

Should said boards of trustees fail to agree upon a division of the funds of the district or upon the length of the term for which the schools of the district shall be maintained, they shall at once certify their disagreement to the county superintendent, who shall proceed to fix the school term of such district and declare the division of the school fund of the district between the white and colored schools therein, endeavoring, as far as practicable, to provide for the schools of such district a school term of the same length.

Sec. 2. All laws and parts of laws in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.

Sec. 3. Whereas, the near approach of the new scholastic year creates an emergency and an imperative public necessity that the constitutional rule requiring bills to be read on three several days be suspended, and that this act take effect and be in force from and after its passage, and it is so enacted.

Approved March 21, 1895.

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.