In 1927, the Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 275, a short but consequential law authorizing municipalities to segregate residential areas by race. Though rarely cited by name today, S.B. 275 exemplified how Jim Crow principles were embedded not only in schools and the private realm, but also in urban planning.

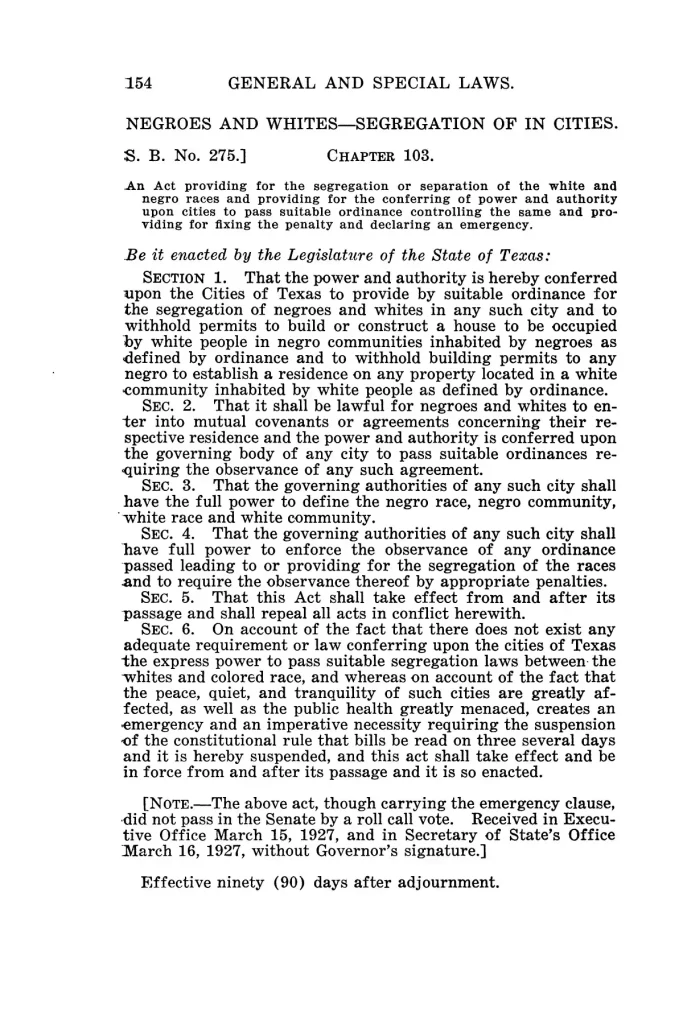

The law was captioned, “An Act providing for the segregation or separation of the white and negro races and providing for the conferring of power and authority upon cities to pass suitable ordinance controlling the same and providing for fixing the penalty.”

S.B. 275 allowed cities to zone for Whites-only and Blacks-only neighborhoods. It also gave cities the power to enforce racially restrictive covenants. These were private agreements where homeowners promised not to sell or rent to Black families. For example, a neighborhood could agree that only White residents were allowed. These covenants helped keep neighborhoods segregated until the Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that they couldn’t be enforced in court.

Earlier segregation laws in Texas had focused primarily on schools, railroads, and public facilities—areas shaped by the “separate but equal” doctrine formalized in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). For example, the legislature had mandated separate railroad coaches for Black and White passengers in 1891 and had enforced school segregation starting in 1893 (though de facto much earlier).

Yet it was not until the 1920s, amid the rise of professional city planning and zoning nationwide, that Texas codified residential segregation through land-use law. S.B. 275 reflected this shift. It allowed cities to impose racial separation not just in social spaces but in the geography of daily life.

This article presents the full text of the bill as a primary source, accompanied by historical context and analysis of how Texas cities, particularly Austin, used zoning and public services to maintain racial separation well into the twentieth century.

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.