Broken Treaties and Vanishing Bison

Between the summer of 1874 and the spring of 1875, the U.S. Army conducted a relentless campaign across the Texas Panhandle that marked the end of sustained Indigenous resistance on the Southern Plains. Known as the Red River War, this campaign involved a network of military expeditions aimed at forcibly removing Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes from the region and confining them to reservations in Indian Territory.

While few large-scale battles occurred, the war succeeded through attrition—destroying food stores, killing horses, burning lodges, and wearing down the mobility and will of the tribal bands.

The roots of the conflict lay in a convergence of broken promises and environmental destruction. Under the terms of the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty, the Southern Plains tribes had agreed to settle on reservations in present-day Oklahoma. In return, the federal government promised food, supplies, and protection from encroachment.

But as the bison herds—the economic foundation of Plains life—were driven to the brink of extinction by commercial hunters, treaty obligations collapsed. Hunters, often escorted by military patrols or left unchecked, invaded traditional hunting grounds, violating the terms of the agreement with little consequence. Tribes grew desperate. Some bands left the reservations and returned to Texas to hunt or raid, hoping to preserve what remained of their independence.

The Spark at Adobe Walls

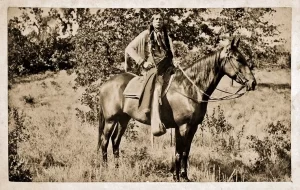

Tensions reached a flashpoint in June 1874 with the Second Battle of Adobe Walls, a failed attack by a coalition of Native warriors on a remote trading post in the Texas Panhandle. Led in part by Comanche leader Quanah Parker and the visionary Kiowa prophet Isa-tai, the assault was meant to send a message to the buffalo hunters and to rally support for resistance.

But the defenders—equipped with long-range rifles and entrenched positions—held firm. Though the attack failed, the incident provided the pretext for the U.S. Army to initiate a large-scale campaign to end all Indigenous presence in the Panhandle.

U.S. Army Offensive

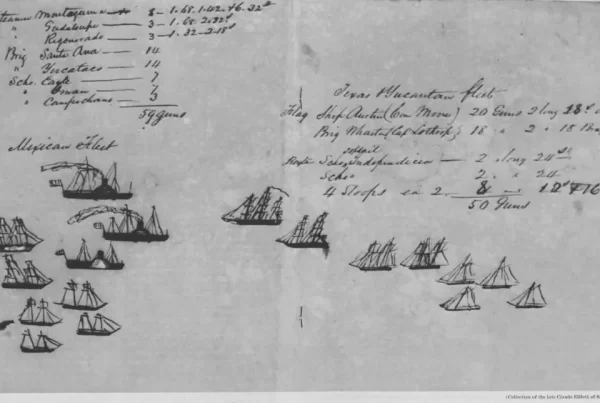

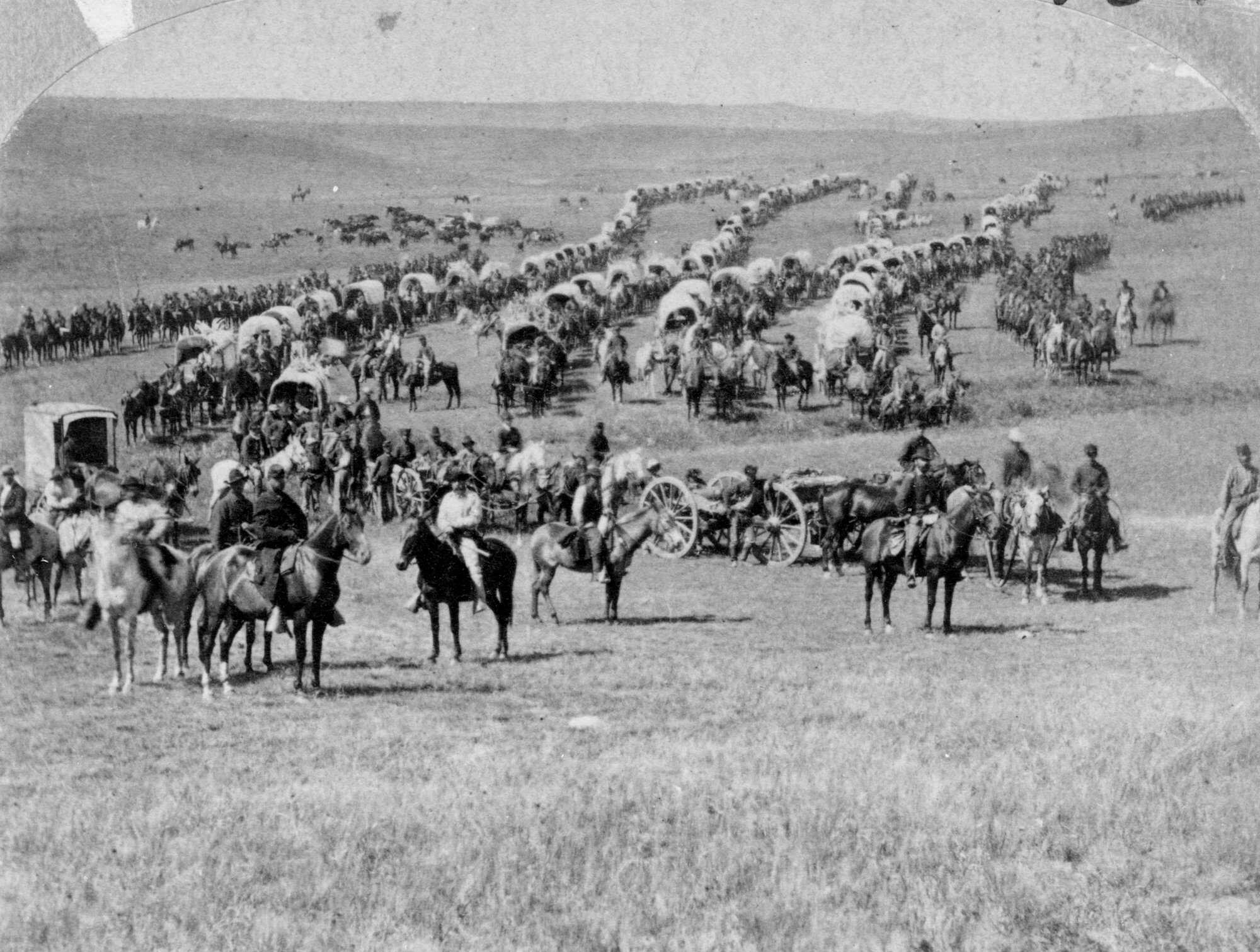

The military response was unprecedented in its coordination. Under orders from General Philip Sheridan, five separate columns of troops advanced into the Texas Panhandle from different directions. Each column was tasked with converging on traditional tribal ranges, cutting off escape routes, and denying the tribes access to supplies or refuge. The columns departed from the following forts:

- Fort Dodge (near modern-day Dodge City, Kansas): Colonel Nelson A. Miles led the 6th U.S. Cavalry and infantry detachments south along the Canadian River.

- Fort Griffin (near Albany, Shackelford County, Texas): Lt. Col. George P. Buell led forces west and north across the Clear Fork and Brazos rivers.

- Fort Concho (present-day San Angelo, Tom Green County, Texas): Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie commanded the 4th U.S. Cavalry, a seasoned frontier unit, along the upper Brazos and Double Mountain Fork.

- Fort Sill (near Lawton, Indian Territory, now Oklahoma): Lt. Col. John W. Davidson approached from the northeast.

- Fort Union (near Watrous, northeastern New Mexico): Major William R. Price’s column moved from the west through the Canadian Breaks.

Terrain, heat, and logistics posed constant challenges. Rivers were dry by midsummer; water holes had to be mapped and guarded. Supply lines were thin. Most columns operated with limited forage, relying on forced marches and field butchering to feed horses and men. Army surgeons treated snakebites, heatstroke, and dysentery. Indian scouts—Tonkawa and Delaware in particular—proved invaluable in tracking movement and locating camps.

Attack at Palo Duro Canyon

On September 28, 1874, Colonel Mackenzie launched the campaign’s most impactful operation. Following reports from scouts, his 4th Cavalry descended the cliffs of Palo Duro Canyon under cover of darkness and reached the canyon floor at dawn. The descent itself—narrow, steep, and rocky—was a calculated risk. The troops surprised several villages comprising mostly women, children, elders, and a rear guard of warriors. Though resistance was limited and scattered, it was not bloodless. U.S. soldiers encountered armed defenders and exchanged fire in short bursts before most Native forces dispersed.

Rather than pursue fugitives, Mackenzie focused on the destruction of resources. His men burned over 450 lodges, destroyed several tons of dried meat, and captured approximately 2,000 horses. After keeping 300 for military use, he ordered the rest shot. The noise of the mass killing echoed up the canyon walls—a psychological blow intended to ensure that even regrouped warriors could not sustain mobility.

Army reports emphasized the strategic value of the raid: it denied shelter, food, transportation, and winter survival. No other engagement during the war matched its combination of terrain mastery, coordination, and material impact.

Ongoing Engagements and the Collapse of Resistance

Elsewhere, fighting continued. The Battle of Buffalo Wallow on September 12, 1874, involved six U.S. personnel—including civilian scouts—who were ambushed by Kiowa and Comanche warriors. Pinned down for hours in a buffalo wallow, the small group held out until relief arrived. Though minor tactically, the engagement became part of Army lore and demonstrated that even small detachments could face lethal resistance.

The Siege of Lyman’s Wagon Train lasted nearly a week and involved over 100 troops defending a vital supply column. Warriors surrounded the train, killing mules and sniping from ridgelines. Effective field fortification and discipline allowed the soldiers to hold out until reinforcements broke the siege. These engagements, though not decisive alone, underscored the level of coordination among tribal groups and the need for vigilance at every stage of the campaign.

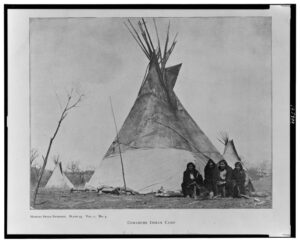

Yet the Army’s campaign of constant patrols, destruction of stores, and relentless pursuit wore down even the most mobile bands. By the end of winter, many had no food or shelter remaining. Disease spread in the cold months. Horses died in the snow. Ammunition ran low. Some bands tried to return to the reservations voluntarily; others held out until spring.

Surrender and Forced Relocation

The final holdouts, led by Quanah Parker, surrendered in June 1875. The 700 Quahadi Comanches who rode into Fort Sill represented the last organized group of free-roaming Southern Plains Indians. By then, the U.S. Army had returned most of its forces to garrison duty, having declared the campaign a success.

The humanitarian cost was undeniable, but largely unremarked upon in official records. Displaced families arrived at reservations destitute. Government rations were inadequate, housing was poor, and disease became endemic. Traditional lifeways were largely extinguished. Horse culture, decentralized mobility, and traditional religious practices tied to the bison hunt—all faded quickly under the constraints of reservation life and Bureau of Indian Affairs regulation.

Yet from the Army’s perspective, the campaign had succeeded with limited casualties and maximum efficiency. Fewer than 50 soldiers were killed in action during the entire war. Native losses were far higher when considering disease, exposure, and starvation.

Legacy and Remembrance

The Red River War effectively ended Native resistance in Texas. The U.S. military demonstrated a new doctrine of warfare against mobile tribal societies: multiple converging forces, destruction of non-combatant infrastructure, and strategic isolation of enemy bands. The campaign avoided major set-piece battles in favor of fatigue, psychological pressure, and material deprivation.

In its wake, the Texas Panhandle was opened to settlement, railroads, ranching, and commercial expansion. Forts like Fort Concho, Fort Griffin, and Fort Richardson transitioned to peacetime roles or were decommissioned. Palo Duro Canyon State Park stands today as the most visible reminder of this campaign, though the interpretive framing often underemphasizes the full consequences.

Only in recent decades have scholars turned serious attention to the civilian experience of the war—the displacement, trauma, and cultural destruction that followed. Still, the Red River War remains a key chapter in both Texas military history and the broader arc of westward expansion: a campaign won through superior logistics, manpower, and the systematic denial of Indigenous autonomy.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History

- Comanches: The History of a People

- The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750–1920

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.