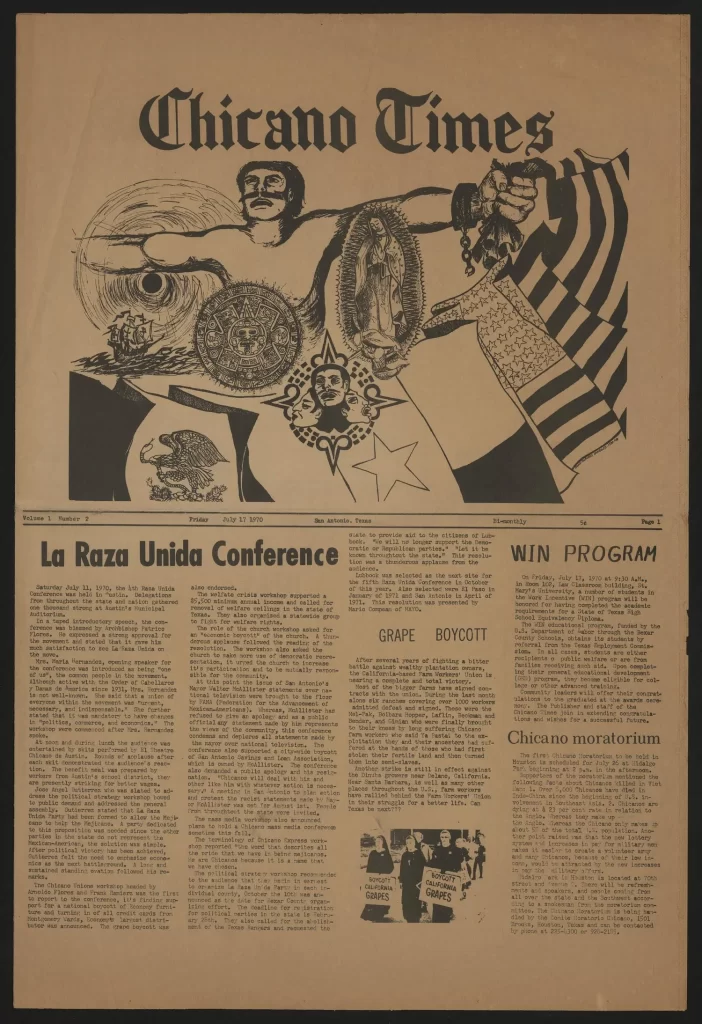

In the spring of 1970, a new political party emerged from the South Texas borderlands—La Raza Unida Party (RUP), or “The United People.” Founded by a coalition of young Mexican American activists, the party arose from a shared frustration with the lack of representation and persistent discrimination faced by Mexican Americans in Texas politics. What began as a regional protest effort soon became a statewide—and briefly, a national—movement for political empowerment, cultural pride, and self-determination.

The movement’s origins lay in the specific social and demographic realities of South Texas. In counties like Zavala, Dimmit, and La Salle, Mexican Americans formed the majority population but remained largely excluded from political power. Institutional barriers such as gerrymandering, at-large elections, language-based voter suppression, and the manipulation of party structures all contributed to the status quo.

For years, both the Democratic and Republican parties failed to represent the community’s interests, according to party leaders. As José Angel Gutiérrez, a founding figure of the movement, derided Mexican-American leaders within these parties as yes-men and “tape recorders,” parroting party talking points. In a fiery 1970 speech, he said, “For a long time we have not been satisfied with this type of leadership that has been picked for us. And this is what a political party does, particularly the ones we have. I shouldn’t use the plural because we only have one, and that’s the gringo party. It doesn’t matter what name it goes by. It can be Kelloggs, All-Bran or Shredded Wheat, but it’s still the same crap.”1

“Most of our traditional organizations will sit there and pass resolutions and mouth off at conventions, but they’ll never take on the gringo. They’ll never stand up to him and say, ‘Hey, man, things have got to change from now on. Que lo que pase [Let whatever happens happen]. We’ve had it long enough!”

The immediate catalyst for the party’s formation was the school board elections in Crystal City, Texas. In April 1970, candidates affiliated with La Raza Unida swept the local elections, including Gutiérrez, who became chairman of the school board. It was a landmark moment—the first time a slate of activist Chicano candidates had seized political control in a Texas municipality. The movement quickly expanded, and within months, RUP was fielding candidates for city council, county commissioner, and eventually governor.

The party’s philosophy rested on the principle of Chicanismo—a political and cultural identity rooted in pride, solidarity, and resistance. Its leaders argued that Mexican Americans could no longer rely on Anglo-led parties to represent their interests. “If you don’t go third party,” Gutiérrez said, “then you’ve got to go the independent route, because there is no other way you are going to get on the November ballot.”2 The language of revolution and resistance permeated RUP’s rhetoric, but so did a pragmatic focus on local issues: bilingual education, jobs, school reform, and equitable political representation.

La Raza Unida drew its initial support from young activists, educators, and working-class voters frustrated with the status quo. But its most enduring success came through coalition-building with community members who had long felt alienated from the political process. Many older citizens, previously cautious or disengaged, became involved and began voting or campaigning.

Although La Raza Unida’s first breakthrough came at the local level, the party quickly adopted a broader political platform aimed at systemic change. At the state level, it called for bilingual and bicultural education, expanded employment opportunities, improved access to healthcare, and the reform of discriminatory law enforcement practices.

On national issues, Raza Unida aligned itself with anti-war, pro-labor, and anti-poverty movements, often critiquing the Vietnam War and federal neglect of Mexican American communities. It demanded greater public investment in colonias and barrios, increased political representation, and an end to what it saw as the Anglo-dominated political establishment. These positions were rooted not only in ethnic solidarity but in a clear left-populist ideology that sought to restructure power from the ground up.

After its early victories, RUP faced formidable obstacles. Mainstream political actors, particularly within the Texas Democratic Party, sought to marginalize the movement. The party was often accused of radicalism, and its leaders were dismissed as “outside agitators” or worse. Internal tensions also emerged, including disagreements over strategy, ideology, and leadership. The centralized control exerted by figures like Gutiérrez alienated some potential allies, and by the mid-1970s, these divisions began to take a toll.

Perhaps more fundamentally, RUP’s efforts to operate as a third party in a two-party system proved unsustainable. Ballot access laws, limited resources, and the structural inertia of U.S. politics all worked against long-term viability. By the late 1970s, RUP had largely dissolved.

Nonetheless, the movement left an indelible mark on Texas politics. The party struck a defiant, proud tone that altered the cultural and political expectations of Mexican American voters and politicians, who had previously been less vocal and more mild. The activists’ willingness to launch outspoken attacks on ‘gringo’ politics and culture marked a clear departure from past patterns, paralleling the ongoing militancy within parts of the Black Civil Rights movement.

More broadly, La Raza Unida proved that Mexican Americans could organize, win elections, and reshape political narratives in the state. Emerging at the intersection of the Chicano Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and the disillusionment with American institutions in the late 1960s and early 1970s, La Raza Unida offered a bold, if ultimately short-lived, experiment in ethnic political mobilization.