The poll tax was a central feature of Texas’s election laws for much of the 20th century, functioning as a barrier to voter participation from its implementation in 1903 until its eventual abolition in the 1960s. While often associated with broader Southern efforts to restrict access to the ballot box, the Texas poll tax had distinctive features that made it one of the longest-lasting and most consequential voting requirements in the state’s history.

Origins and Enactment in Texas

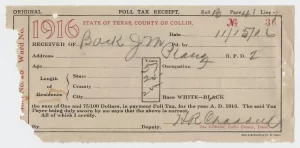

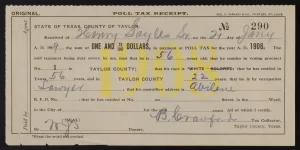

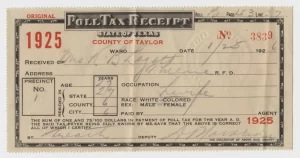

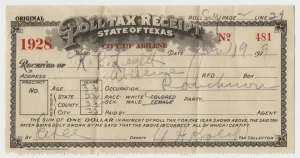

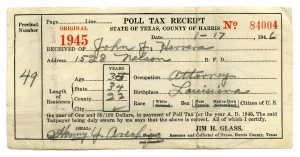

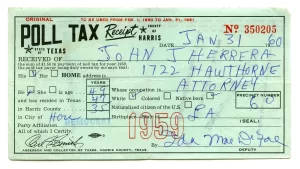

Texas formally adopted the poll tax as a requirement for voting through a constitutional amendment passed in 1901 and ratified by popular vote in 1902. The amendment required eligible voters to pay a cumulative annual tax, typically ranging from $1.50 to $2.00, by January 31 of each year in order to be eligible to vote later that year. This measure took effect for the 1903 election cycle.

The stated purpose of the poll tax was to improve the quality and “responsibility” of the electorate. Supporters claimed that requiring a payment would reduce voter fraud and promote civic responsibility. In practice, the law excluded significant portions of the population—especially African Americans, Mexican Americans, and poor whites—from the electoral process, regardless of their eligibility on other grounds.

Broader Context and Precedents

Although Texas was not the first Southern state to implement a poll tax, it joined a wave of such laws enacted across the region following the end of Reconstruction. Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia had adopted poll taxes during the late 19th century, typically as part of broader constitutional revisions that also included literacy tests and property requirements.

In Texas, the shift toward formalized disenfranchisement came more gradually. Earlier efforts to limit voter participation had focused on primary elections and registration procedures. The poll tax marked a more systematic and statewide approach to shaping the electorate. It came shortly before Texas also institutionalized racially exclusive primaries, reinforcing a layered structure of voter suppression during the Jim Crow era.

Function and Enforcement

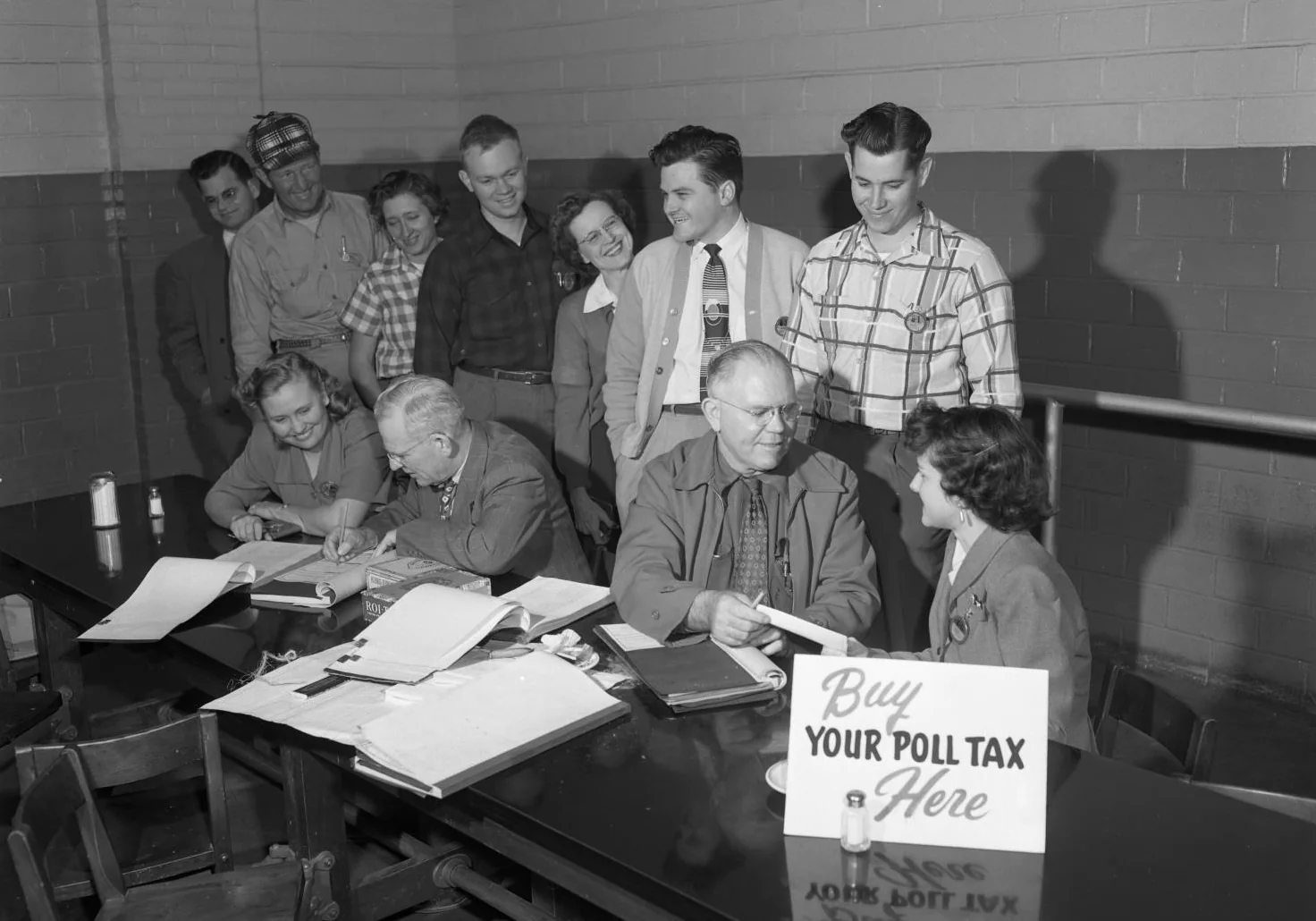

The mechanics of the poll tax created barriers at multiple points in the electoral process. Payment had to be made in person months before an election, often at a county courthouse or other designated office. Voters had to retain their tax receipt and present it at the polls as proof of eligibility. Missing the payment deadline—even for reasons of illness, relocation, or misunderstanding—meant exclusion from voting for the rest of the year.

While the tax amount may appear modest by modern standards, it represented a substantial burden for many Texans at the time, particularly agricultural laborers and families with limited cash income. The financial impact was compounded by the logistical challenge of reaching payment locations, especially in rural areas.

Enforcement varied across counties, but the law was generally administered in a manner that disproportionately burdened the state’s poorest and most marginalized citizens. County officials had broad discretion in how tax rolls were maintained and checked, and instances of administrative irregularities were common. The cumulative effect was to reduce voter turnout and entrench political power among those already in office.

Political Impact

Voter turnout fell sharply after the implementation of the poll tax, especially in counties with high concentrations of African American or Mexican American residents. The poll tax helped insulate the Democratic Party’s dominance in state politics during the one-party era, as it dampened political competition and minimized the likelihood of coalition-building across racial or economic lines.

Although its impact was most acutely felt by racial minorities, the poll tax also affected low-income White voters, particularly in rural areas. The result was a narrower and more demographically homogeneous electorate, with wide-ranging policy consequences.

However, because the poll tax amount was fixed in statute and not indexed to inflation, it became less financially burdensome over time. By mid-century, in the years before the practice ended, the poll tax was not a significant financial cost for an average Texan, especially compared to 1903 when the tax began. Even so, its impact on voter participation remained significant due to logistical and psychological barriers rather than sheer cost.

Challenges and Decline

Efforts to repeal or modify the poll tax met with limited success in the early decades of the 20th century. Civil rights organizations, labor unions, and some political reformers criticized the tax, but statewide repeal campaigns repeatedly failed. The entrenchment of the tax in the state constitution made it difficult to reverse through ordinary legislation.

Momentum for change increased during the post–World War II era, as national attention to voting rights intensified. Legal challenges in other states, along with growing criticism of the poll tax as an outdated and undemocratic barrier, gradually reshaped the political landscape.

A major turning point came with the ratification of the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1964, which prohibited poll taxes in federal elections. However, Texas and several other states continued to enforce the tax for state and local elections, prompting further legal battles.

Abolition

The definitive end to the Texas poll tax came through the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1966 decision in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, which held that poll taxes in state elections violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Although the case did not originate in Texas, its ruling applied nationwide. Texas formally repealed its poll tax requirement the following year through constitutional amendment, removing what had long been one of the most persistent instruments of voter exclusion in the state.