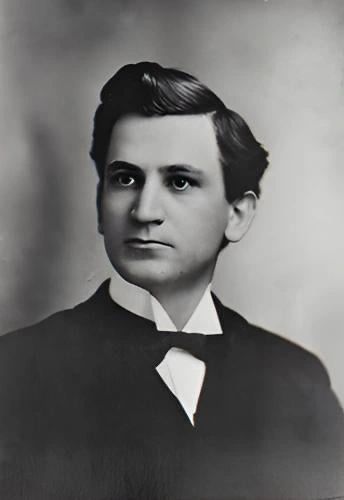

Pat Morris Neff was a Baptist moralist and Wilsonian Democrat who served four years as governor of Texas (1921-1925) in the twilight of the Progressive Era. A talented orator and campaigner, Neff sought to reconcile Progressive labor ideals with a deeply religious view of public duty. He was a strong advocate for the public education system and environmental conservation. Later, he served as president of Baylor University in his hometown, Waco.

Roots and Formation

Born on November 26, 1871, in Coryell County, Neff was raised by Noah and Isabella Neff on a small farm near McGregor. His mother’s faith and discipline became central to his worldview; her later donation of land for Mother Neff State Park symbolized the family’s creed that moral stewardship belonged in both home and government.

Neff graduated from Baylor University in 1894 and earned a law degree from the University of Texas in 1897. He began practicing law in Waco and quickly developed a reputation for clarity, fairness, and fierce advocacy. He married Myrtle Mainer, a fellow Baylor alumna, in 1899.

Early Career and Legislative Reform

Neff’s political career began in 1898, when he was elected to the Texas House of Representatives. Serving until 1905, and as Speaker in his final term, he aligned with the rising Progressive movement: pro-education, anti-monopoly, and sympathetic to organized labor. His Baptist ethics translated into civic responsibility rather than partisan ideology—a blend of moralism and reform that appealed to urban workers as well as rural reformers.

After leaving the legislature, Neff served as McLennan County attorney from 1906 to 1912. He became known for aggressive prosecutions and an austere sense of justice, trying hundreds of cases with few acquittals. Yet even then, his speeches emphasized rehabilitation, education, and temperance—recurring themes in his later policies as governor.

The 1920 Campaign: Reform versus Reaction

Neff had been inactive politically for several years when he decided to run for governor in 1920. He later wrote in a memoir, “No one solicited me to run for Governor. I did not ask permission of anyone to get into the race. Just as a freeborn American, and as a native son of Texas, without a conference with or advice from anyone, I announced my candidacy.”

“Eighteen years had passed since I had been Speaker of the House of Representatives. During this intervening period, I had devoted my time and energies to the practice of law, to the exclusion of any active participation in personal or factional politics. No political alignments, therefore, were mine… No business interests had any concern in, or took any notice of, my candidacy.”1

Neff’s 1920 campaign for governor played out as a clash between two political worlds. His opponent, former U.S. Senator Joseph Weldon Bailey, represented the old Bourbon Democratic order: anti-prohibition, anti-suffrage, and hostile to reform. Neff campaigned from his car across thirty-seven counties, often speaking in churches and union halls alike, framing moral virtue as compatible with social progress.

He declared himself a friend of organized labor and supported the creation of cooperative marketing associations to help Texas farmers. In an era when labor unrest was frequently demonized, Neff’s rhetoric was notable for its restraint and sympathy. His victory over Bailey ended the latter’s political influence and signaled a generational shift in Texas politics—from machine loyalty to a reformist conscience.

A Reform Agenda in Office

Taking office in January 1921, Neff entered with a crowded agenda: improving public schools, reorganizing state agencies, advancing public health, and developing state parks. Education remained central; he increased funding for rural and vocational training and oversaw the founding of Texas Technological College and the reorganization of the state teachers college system in 1923.

His labor record was mixed but earnest. He advocated mediation over confrontation, supported fair wage standards, and promoted industrial peace through education and regulation. His veto of a minimum-wage bill in 1921 drew criticism, but his reasoning was technical—he opposed its narrow exemptions rather than the principle itself. In his own words, a “just and workable” minimum wage remained possible under better legislation.

Reform and Restraint

Neff was a “Progressive” in the Wilsonian Democratic sense, not in the sense that the word is used in the 21st century. He advocated for certain reforms but also embraced a law-and-order approach to governing that some modern Progressives might reject. A lifelong prohibitionist, Neff linked social disorder to moral decay. In January 1922, he deployed Texas Rangers and National Guard to the oil boomtown of Mexia to crack down on bootlegging, gambling, prostitution, and robbery.

Later that year, Neff declared martial law in Denison during a violent rail strike. This incident illustrated the limits of Neff’s support for organized labor. Though he supported workers’ rights to organize and strike, he did not tolerate violence. Neff reduced gubernatorial pardons, expanded law enforcement, and strengthened administrative discipline. His administration marked a decline in patronage politics and an early move toward bureaucratic governance.

Much of Neff’s governing agenda was stymied by the legislature. But he succeeded in securing the creation of a state park system and personally donated land, along with his mother, to establish Mother Neff State Park, among the first parks in the state system. His vision for public recreation carried both civic and spiritual overtones—an attempt to sanctify the Texas landscape through stewardship.

Ascent of the Ku Klux Klan

Before and during Neff’s time in office, the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed a resurgence in Texas. Some contemporary critics and historians have associated Neff with the Klan, or at least blamed him for failing to firmly oppose it, describing his silence as a lasting stain on his record.

However, other historians have characterized this view as mistaken.2 Although Neff generally adopted a “policy of silence” regarding the Klan, he privately disapproved of it, and occasionally acted or spoke publicly against it. For example, during the 1921 legislative session, Neff supported a resolution by Representative Wright Patman that implicitly condemned the Ku Klux Klan.

The resolution was merely a moral statement, without policy implications; it condemned masked bands of vigilantes and, implicitly, racial lynchings. Due to Klan influence in the legislature, the resolution was a lost cause, yet Neff spoke in favor of it anyway, saying it targeted “secret organizations organized for the purpose of masking and disguising themselves and violating the laws of this state by inflicting punishment upon persons against whom no legal complaint has been filed.”3 More often, however, Neff avoided questions of race and the Klan.

Neff was neither an outspoken segregationist, nor did he challenge the reigning Jim Crow system. Neff’s silence on the Klan issue contrasted with the stance of his successor, Miriam Ferguson, who ran on an anti-Klan platform. His neutrality on the issue may have helped him win reelection in 1922, at a time when the Klan was gaining in popularity. Neff’s second term was mostly uneventful, marked by consolidation of prior reforms and a quiet style of governance.

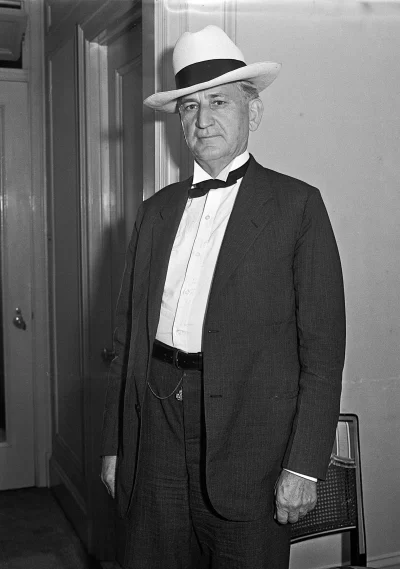

Declining a third term in keeping with tradition, he left office in 1925 with a mixed reputation—admired for integrity, criticized for rigidity. Neff was a talented orator given to grand gestures and high ideals. In his farewell address in 1925, he told his successor, Miriam Ferguson,

“When you go down to the office, the people’s office, which a few moments ago I vacated, you will find it cleared of all except three things. I left hanging above your chair for that help, help and inspiration that comes from lofty ideals and sacrificial service, the portrait of Woodrow Wilson. By your side you will observe a white flower, emblematic, I hope, of the pure motives that shall prompt your every act. On your desk you will find the open Bible with this verse marked: ‘They word is a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path.’ This Book of Books is my gift to you and to all your successors in office for their chart and comps while directing the ship of state.”4

Notwithstanding Neff’s hopes and blessings, his successor’s administration ended up being marred by credible allegations of corruption.

Later Public Service

After leaving office, Neff remained active in civic and educational causes. He chaired the Texas Education Survey Commission (1925–26), served as president of the Baptist General Convention of Texas (1926–28), and led the Texas Watersheds Association in the late 1930s.

In 1927 President Calvin Coolidge appointed him to the United States Board of Mediation, which handled labor disputes in interstate commerce. Two years later, Governor Dan Moody named him to the Texas Railroad Commission, one of the state’s most powerful regulatory bodies. Neff served there until January 1, 1933, gaining a reputation for fairness and efficiency.

He was occasionally considered for higher office, including for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1924, but he declined both opportunities.

President of Baylor University

In 1932, Neff accepted the presidency of Baylor University, inheriting a financially strained institution during the Great Depression. His administrative discipline, shaped by years of public service, stabilized the university and laid groundwork for its later expansion.

Enrollment quadrupled during his tenure, and the campus doubled in size. Yet Neff’s emphasis on moral order continued to define his leadership. He enforced strict behavioral codes, curbed perceived excesses, and often spoke of education as a sacred trust rather than an intellectual experiment.

During his final years at Baylor, Neff also served as president of the Southern Baptist Convention (1942-1945), which eventually became the largest Christian denomination in the United States.

In 1947, at age seventy-six, he stepped down as president of Baylor and was named president emeritus.

Neff died in Waco on January 20, 1952, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. His wife, Myrtle, survived him by a year. Baylor’s Pat Neff Hall, the university’s main administration building, is named in his honor. Mother Neff State Park, located southwest of Waco, is named in honor of the governor’s mother, Isabel Neff, who donated land for the creation of a state park.

- Pat M. Neff, The Battles of Peace (Fort Worth: Pioneer Publishing Company, 1925), 7. ↩︎

- Mark Stanley, Booze, Boomtowns, and Burning Crosses: The Turbulent Governorship of Pat M. Neff of Texas, 1921–1925 (Master’s thesis, University of North Texas, 2005), https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc4834/m2/1/high_res_d/thesis.pdf ↩︎

- “Nine Representatives Sign Resolution Denouncing Work of Masked Bands,” Austin Statesman, July 24, 1921; “Klan Debate Stirs House,” Austin Statesman , July 25, 1921; “Governor Neff Paves Way for Anti-Masker Legislation, Austin Statesman , Aug. 1, 1921. ↩︎

- Neff, Battles of Peace, 269–70. ↩︎