From the days of the Republic of Texas to the campaigns of the Civil War, Texans repeatedly cast their gaze westward toward New Mexico. Fired by ambition, commerce, and resentment, they launched at least three expeditions to seize or raid the region—each ending in failure.

Though often forgotten, these episodes offer a vivid window into the violent fluidity of the 19th-century Southwestern frontier, and they played a direct role in shaping the modern boundary between Texas and New Mexico.

The Santa Fe Expedition (1841)

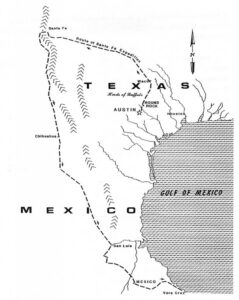

President Mirabeau B. Lamar, eager to assert the Republic’s claim over the Rio Grande as its western boundary, organized a civilian-military venture in 1841 to seize control of the lucrative Santa Fe Trail and bring New Mexico under Texan jurisdiction. Though presented as a diplomatic-commercial mission, the so-called Santa Fe Expedition was, in practice, a thinly veiled act of aggression, and it was perceived as such by Mexican authorities from the outset.

Nearly 320 men set out from central Texas, including traders, surveyors, and a small armed escort. They suffered from poor planning, no clear military objective, and limited knowledge of the terrain. The expedition ran out of supplies, quarreled internally, and was ultimately surrounded and captured by Mexican forces near Santa Fe without offering resistance.

From the Mexican perspective, the incursion was a blatant violation of national sovereignty. Authorities in New Mexico, led by Governor Manuel Armijo, responded decisively. Viewing the group not as envoys or traders but as invaders, Armijo mobilized militia and regular troops to intercept the Texans. After a brief standoff, the exhausted and demoralized expedition surrendered without a fight.

The prisoners were marched over a thousand miles to Mexico City in chains, where the government used their capture as both a symbolic and practical repudiation of Texan ambitions. In official statements and public spectacle, the expedition was portrayed as further evidence of the illegitimacy and lawlessness of the Republic of Texas. Rather than triggering diplomatic dialogue, the expedition hardened Mexican resistance to Texan and, more broadly, American expansionism. Lamar’s administration suffered a political setback at home, while in Mexico, the event bolstered nationalist sentiment and reaffirmed the government’s resolve to defend its northern territories.

The Snively and Warfield Expeditions (1843)

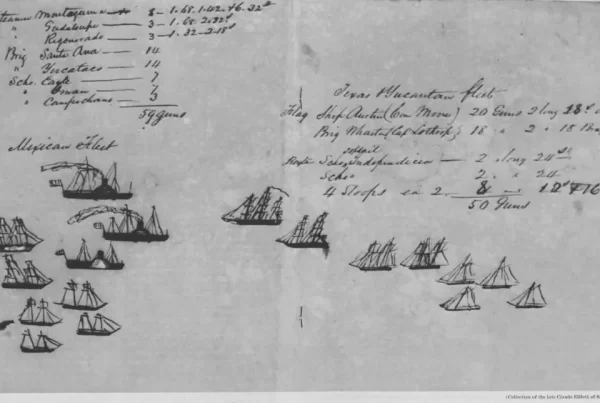

In 1843, the Republic of Texas authorized another attempt to retaliate against Mexico and assert power along the Santa Fe Trail. This time, the effort had a sharper edge: it would be a raid.

Captain Charles Warfield led a small party of about 24 men deep into New Mexico Territory. On May 13, 1843, his men ambushed a Mexican trade caravan near Mora, killing three civilians and seizing approximately 70 horses. A counterattack by local residents drove the Texans off, recovering the stolen property and forcing Warfield to flee.

Soon after, Jacob Snively organized a larger force known as the “Battalion of Invincibles,” with the backing of the Texan government. His orders were to intercept and disrupt Mexican commerce along the Santa Fe Trail as retaliation for Mexican raids into Texas. The expedition set out from the Red River with roughly 175 to 300 men.

On June 20, 1843, Snively’s men ambushed a Mexican military escort of traders, killing 17 soldiers and capturing over 80 prisoners. But darker actions followed. A rogue band affiliated with the expedition murdered a well-known merchant, Antonio José Chávez, dumping his body in a ravine and looting his goods. The killing shocked U.S. authorities, who viewed the murder as banditry.

On June 30, U.S. Dragoons under Capt. Philip St. George Cooke intercepted the Texans in what is now Kansas, disarmed them for violating American neutrality, and released them without charges. The incident further embarrassed the Republic of Texas, revealing that its ambitions had devolved into lawless violence.

Comanche Power: A Check on Westward Expansion

Texans’ designs on New Mexico were limited not only by their military ineptitude, but also by the indebtedness of the new republic and by another key factor: the indigenous nations that militarily dominated the high plains, particularly the Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche.

Spanish, Mexican, and later U.S. officials struggled for decades to contain these highly mobile and militarily adept horsemen. Their dominance of West Texas and the present-day Panhandle made the crossing between the populated parts of Texas and New Mexico perilous and difficult.

Long before Texans mounted formal invasions, New Mexico’s settlements had become seasoned in the rhythms of violence stemming from the Apache and Comanche, whose mounted raiding parties had, for decades, pushed deep into New Mexican territory from the Texas plains. These raids, frequent and devastating, were aimed at acquiring horses, captives, and trade goods, and exacting tribute.

Indian raids left an enduring mark on the region’s defensive posture. By the early 19th century, communities from Taos to Santa Cruz had fortified their plazas, trained militias, and developed a collective vigilance born of necessity. This state of preparedness meant that when Texans later approached under banners of trade, diplomacy, or military assertion, they encountered a borderland already hardened against external threats.

Confederate Ambitions: The Sibley Campaign (1862)

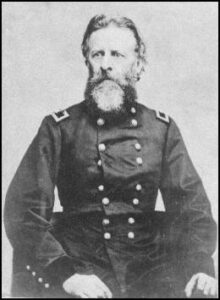

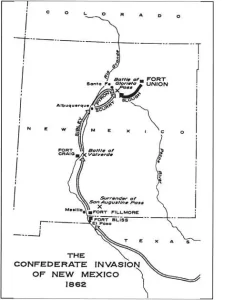

Two decades after the Republic of Texas failed to establish control over New Mexico—and in a region still reeling from years of Indigenous raids—Texans again marched westward, this time under the banner of the Confederacy. In early 1862, Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley led a Confederate army of roughly 2,500 men, most of them Texans, northward from El Paso into Union-held New Mexico Territory.

Sibley’s grand strategy extended far beyond New Mexico. The Confederate high command had authorized efforts to create a transcontinental corridor stretching from Texas to California, with hopes of seizing Union forts, tapping into the Colorado goldfields, and ultimately securing access to the Pacific. Confederate Arizona Territory had already been declared in early 1862, carved out of the southern halves of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico, with Mesilla serving as its provisional capital. If Sibley could hold the Rio Grande and push north into Colorado, he would be positioned to support those gains and expand Confederate control throughout the far Southwest.

Initially, the plan seemed plausible. Sibley’s troops defeated Union forces at the Battle of Valverde in February 1862 and quickly moved north to occupy Albuquerque and Santa Fe. But logistical weaknesses soon became fatal. The Confederate force had no real supply base, was operating far from friendly territory, and lacked support from local civilians. Desertions mounted, and discipline frayed.

The campaign’s collapse came at the Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 26–28, 1862. While Confederate forces engaged Union defenders in the rugged mountain corridor east of Santa Fe, a flanking column of Union troops—including newly arrived volunteers from Colorado—located and destroyed the Confederate supply train hidden in Apache Canyon. Though the fighting was tactically inconclusive, the loss of supplies rendered further advance impossible.

The Union troops who halted the invasion were drawn from two key sources: regular Army units under Colonel Edward Canby, based at Fort Craig, and emergency volunteer companies from the Colorado Territory, sometimes referred to as “Pike’s Peakers.” These Colorado men had marched hundreds of miles through winter snows to reinforce New Mexico, arriving just in time to alter the balance.

The Confederate withdrawal was slow, humiliating, and deadly. Soldiers abandoned artillery, wagons, and wounded men as they staggered back toward Texas, many dying of exposure and hunger. Sibley’s personal conduct—marked by indecisiveness and rumored drunkenness—came under criticism, and although he was never court-martialed, his military career effectively ended. More importantly, the failure of the New Mexico campaign dealt a fatal blow to Confederate ambitions in the far West. Efforts in Arizona and California soon withered, and the dream of a Confederate empire stretching to the Pacific died in the mountain passes east of Santa Fe.

Drawing the Line: How Failed Invasions Shaped the Border

The failure of Texas’ incursions into New Mexico underscored the limits of Texas’s reach and helped define the eventual boundary with New Mexico. During its time as a republic, Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its western boundary—an assertion that, on paper, extended Texan territory deep into what is now eastern New Mexico. In practice, however, Texas exerted no meaningful governance or settlement in those regions. The claim reflected more the grandiosity of Texan territorial ambitions than any enforceable control on the ground.

When Texas joined the United States in 1845, it brought those expansive claims into the Union. The U.S. inherited the resulting boundary dispute with New Mexico, which remained unresolved even after the conclusion of the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) defined the outer boundaries of U.S. territory but left internal borders unsettled.

Tensions escalated until the Compromise of 1850, in which Texas agreed to relinquish its claims to eastern New Mexico in exchange for $10 million in federal compensation. The boundary established by the compromise marked a clear limit to Texas’s expansionist aspirations. It was not the Rio Grande, but a negotiated line—one drawn in response to the realities of failed incursions and the impracticality of Texas’s earlier grandiose claims.

Legacy and Memory

The Texan attempts to seize New Mexico occupy a complex place in historical memory. The 1841 Santa Fe Expedition is occasionally portrayed as a bold—if ill-fated—venture, while the Snively and Warfield raids of 1843 are less well known, often omitted from broader narratives of Texan or American expansion. The 1862 Confederate campaign under Henry Sibley has received more sustained attention from historians, particularly in the context of Civil War operations in the trans-Mississippi West.

Taken together, these efforts illustrate a recurring strategic interest in the Southwest by both the Republic of Texas and, later, Confederate authorities. None of the incursions succeeded in altering the territorial status of New Mexico, but they influenced events more broadly. The episodes remain significant in understanding how Texas positioned itself in the broader contest for power in the American West.

Sources:

- Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)

- National Park Service (Glorieta Pass Battlefield)

- Ralph A. Smith, “The Snively Expedition,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848); Compromise of 1850

- U.S. Army records and reports on the 1843 expedition