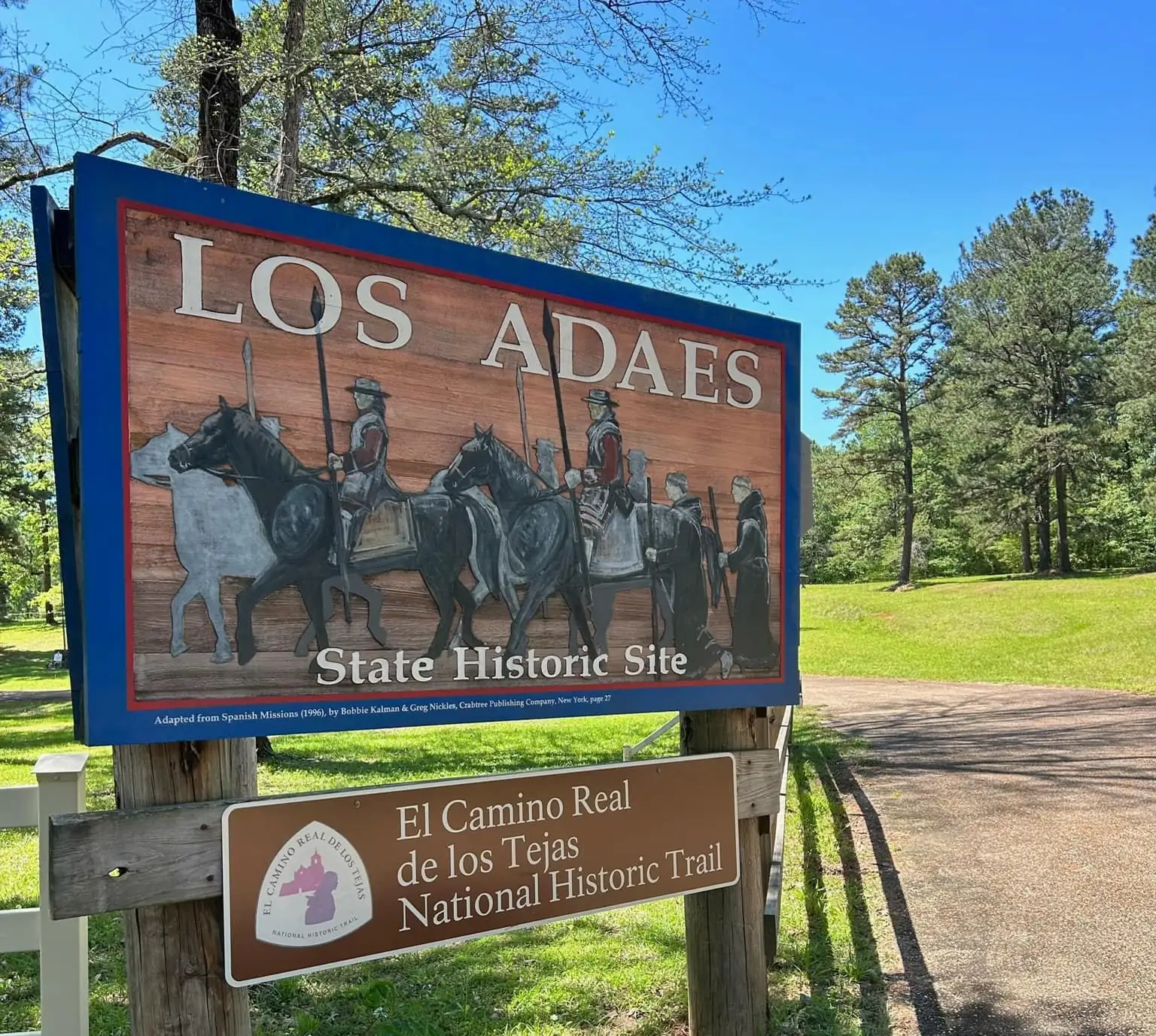

From 1729 to 1772, the small and remote outpost of Los Adaes served as the first official capital of Spanish Texas. Located near present-day Robeline, Louisiana—just a few miles west of the French fort at Natchitoches—Los Adaes was the easternmost outpost of Spain’s North American frontier. For over fifty years, this presidio and mission complex functioned as the administrative and military center of Texas, anchoring Spain’s territorial claims and guarding against French expansion from Louisiana.

Though largely forgotten today, Los Adaes played a central role in the colonial history of Texas. It embodied Spain’s defensive approach to the region and served as an enduring—if isolated—symbol of imperial presence in the East Texas borderlands.

European Rivalries and the Chicken War

Los Adaes was established in the aftermath of a minor but disruptive event known as the Chicken War. In 1719, during the War of the Quadruple Alliance—a European conflict pitting Spain against a coalition of France, Britain, the Dutch Republic, and Austria—a small French force captured a Spanish mission in East Texas and looted it for supplies, including, reportedly, chickens.

Though the incident was brief and bloodless, it exposed how weakly defended the region was. Spanish missionaries and settlers retreated all the way to San Antonio, leaving the frontier open.

The broader conflict reflected growing competition among European powers for territory, trade routes, and military advantage. Spain’s North American holdings were vast but thinly defended, while France had established a strong foothold in Louisiana and was pushing westward. British influence was also growing in the Gulf region. The Spanish Crown recognized that it needed to assert a firmer presence in Texas or risk losing it entirely to rival powers.

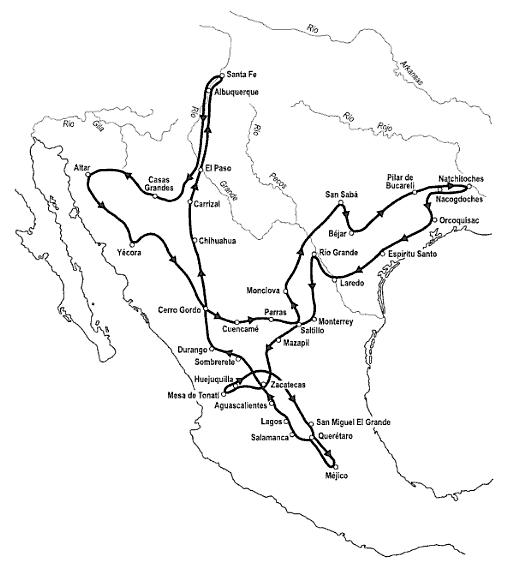

In response, the Spanish government sent the Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo to restore control and reinforce the frontier. In 1721, Aguayo founded Presidio Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes near the French settlement of Natchitoches. He also reestablished Mission San Miguel de Linares de los Adaes, originally founded in 1717 by Domingo Ramón and abandoned during the French incursion of 1719.

Capital of Spanish Texas

The new presidio was staffed with over 100 soldiers, making it the largest garrison in the Texas region at the time. Its primary purpose was to block French encroachment and to protect Spain’s fragile claim to the northeastern corner of New Spain. The presence of a fortified presidio so close to French Louisiana was an unmistakable political message: Spain intended to hold its ground.

In 1729, Los Adaes was officially designated the capital of the province of Texas by order of the Spanish viceroy. This administrative elevation reflected its strategic location, directly facing the French frontier. From that point forward, the royal governor of Texas resided at Los Adaes, overseeing civil and military affairs from what was then considered the most critical point of Spanish defense.

Relations with Native Peoples

The garrison size was reduced to about sixty men shortly thereafter, as the region remained peaceful and the nearby Caddoan-speaking tribes, including the Adaes, were largely friendly to the Spanish. These Indigenous groups had longstanding rivalries with the Lipan Apaches to the west and saw the Spanish as a useful buffer.

Despite cordial relations, the Franciscan missionaries at Los Adaes were unsuccessful in attracting Native converts to live permanently at the mission. The local tribes were self-sufficient and preferred to remain in dispersed hamlets. In 1768, the College of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zacatecas, which supervised the mission, officially ceased its efforts in the area and abandoned the mission project altogether.

Life at the Edge of Empire

Life at Los Adaes was marked by isolation and hardship. The settlement was over 300 miles from other Spanish centers and was linked to central Texas only by a primitive overland route—sometimes referred to as a Camino Real, though in practice it was little more than a trail prone to flooding and delays.

Out of necessity, the Adaesans relied heavily on the nearby French post at Natchitoches for food and supplies, especially staples like corn, beans, and wheat. Though trade with the French was technically illegal, Spanish officials repeatedly relaxed enforcement on food commerce. Other forms of illicit trade—especially involving French goods used in Indigenous diplomacy—continued despite royal restrictions.

Over time, the Los Adaes community developed its own frontier identity. In addition to soldiers and friars, the civilian population included craftsmen, woodcutters, blacksmiths, cattle tenders, and traders who engaged in the local deerskin trade. Intermarriage with French and Indigenous families was common, and the community exhibited a mix of cultures uncommon in more centralized parts of New Spain.

The 1730s brought a particularly difficult period, with crop failures, supply shortages, and harsh weather threatening the survival of the settlement. Although conditions improved in later decades, Los Adaes never flourished in the way Spanish authorities had hoped.

The End of Los Adaes

The balance of power in the region shifted dramatically in 1762, when the Seven Years’ War—known in the American colonies as the French and Indian War—concluded with the Treaty of Paris. France ceded Louisiana to Spain, eliminating the French threat that had originally justified the establishment of Los Adaes. With no more need for an eastern defensive outpost, Spain began consolidating its far-flung frontier holdings.

In 1766–1767, the Marqués de Rubí conducted a royal inspection of all presidios in northern New Spain and recommended closing many of them, including Los Adaes. Acting on his advice, the Crown issued the Royal Regulation of 1772, ordering the closure of Los Adaes and the transfer of the provincial capital to San Antonio de Béxar.

The settlers at Los Adaes—numbering nearly 500—were given short notice and ordered to move to San Antonio. They complied, but many were unhappy with the new location. After a brief and difficult stay at the Bucareli settlement along the lower Trinity River, most returned east without official permission. Their independent spirit, shaped by decades of isolation, led them to establish what would become the town of Nacogdoches.

Legacy

For over fifty years, Los Adaes was the administrative, military, and symbolic heart of Spanish Texas. It represented Spain’s attempt to stake a permanent claim to a contested frontier, using a blend of religious, military, and civil institutions. While the mission ultimately failed and the presidio was abandoned, the settlement left a lasting legacy in the form of cultural blending, geographic influence, and the eventual founding of new East Texas communities.

Today, the Los Adaes State Historic Site preserves part of the original location. Ongoing archaeological research and historical scholarship continue to reveal the complex life of this forgotten capital—offering modern Texans a deeper understanding of how Spain governed, defended, and ultimately surrendered its early claims to the region.

Related Books

Dive deeper into this topic by purchasing any of these recommended books. As an Amazon Associate, Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.

- Spanish Texas, 1519–1821: Revised Edition

- Los Adaes, the First Capital of Spanish Texas

- History of the Indies of New Spain

- Spanish New Orleans: An Imperial City on the American Periphery, 1766–1803

- Spanish Louisiana: Contest for Borderlands, 1763–1803

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “Article”, “mainEntityOfPage”: { “@type”: “WebPage”, “@id”: “https://texapedia.info/los-adaes-texas/” }, “headline”: “Los Adaes: The Forgotten Capital of Spanish Texas”, “alternateName”: “Presidio Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes and the Eastern Frontier of New Spain”, “description”: “Located near the French border, Los Adaes was a strategic presidio and mission that anchored Spain’s claim to East Texas during an era of European rivalry.”, “author”: { “@type”: “Organization”, “name”: “Texapedia”, “url”: “https://texapedia.info” }, “publisher”: { “@type”: “Organization”, “name”: “Texapedia”, “url”: “https://texapedia.info”, “logo”: { “@type”: “ImageObject”, “url”: “https://texapedia.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/texapedia-logo-dark.png” } }, “image”: “https://texapedia.info/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/los-adaes-spanish-texas.jpg”, “datePublished”: “2025-06-15”, “dateModified”: “2025-06-15”, “articleSection”: [ “Military History”, “Spanish Texas (1690–1821)” ], “isPartOf”: { “@type”: “Collection”, “name”: “Spanish Texas”, “url”: “https://texapedia.info/history/spanish-texas/” }, “keywords”: [ “Los Adaes”, “Spanish Texas”, “Presidio Nuestra Señora del Pilar”, “Chicken War”, “Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo”, “Caddo tribes”, “Marqués de Rubí”, “Natchitoches”, “New Spain”, “Nacogdoches” ], “about”: [ { “@type”: “Place”, “name”: “Los Adaes”, “description”: “The first official capital of Spanish Texas (1729–1772), located near present-day Robeline, Louisiana.” }, { “@type”: “Event”, “name”: “Chicken War”, “startDate”: “1719”, “description”: “A minor conflict during the War of the Quadruple Alliance in which French forces briefly seized a Spanish mission, prompting Spain to strengthen its Texas frontier.” }, { “@type”: “Person”, “name”: “Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo”, “description”: “Spanish colonial official who reasserted Spanish control in East Texas and established Los Adaes presidio in 1721.” }, { “@type”: “Person”, “name”: “Marqués de Rubí”, “description”: “Royal inspector whose 1767 report recommended the closure of Los Adaes and other frontier presidios.” } ], “spatialCoverage”: { “@type”: “Place”, “name”: “East Texas Borderlands”, “geo”: { “@type”: “GeoCoordinates”, “latitude”: “31.695”, “longitude”: “-93.307” } }, “temporalCoverage”: “1721-1772”, “sameAs”: [ “https://tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/los-adaes”, “https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Adaes”, “https://www.nps.gov/places/los-adaes-state-historic-site.htm” ] }