Origins of a Holiday

Juneteenth is an official holiday celebrated annually on June 19th, which commemorates the liberation of slaves in the United States in 1865 at the end of the U.S. Civil War.

The holiday began as an unofficial celebration among freed slaves in Texas, spread to other states, and won recognization as an official state holiday in Texas in 1980, before becoming a federal holiday in 2021.

The U.S. President signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act on June 17, 2021. The U.S. Senate had approved the act by unanimous consent, and the U.S. House approved it by a vote of 415 to 14, signaling strong bipartisan support for commemoration of the holiday.

The holiday is also known as Jubilee Day, Freedom Day, Liberation Day, or Emancipation Day.

Relationship to the Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln’s had declared, “All persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

The advance of Union armies into the Confederacy, including Texas, resulted in freedom for the slaves in the occupied areas. This preceded the 13th Amendment to the U.S Constitution passed by Congress in 1865, after the end of the Civil War, ending legal slavery officially.

Juneteenth takes its name from the date of an 1865 proclamation by a U.S. army commandeering Texas, which he issued on June 19th, declaring slaves in Texas to be free.

On June 19, 1865, U.S. Major-General Gordon Granger declared that “in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” General Granger’s order implemented in Texas the national Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln’s two and a half years earlier.

Traditional Juneteenth Celebrations

African Americans have been celebrating Juneteenth since 1866, though the day only became an official state holiday in Texas in 1980. Legally, the day is called “Emancipation Day in Texas.”

Celebrations of Juneteenth began to spread to other states—and merge with existing emancipation rituals elsewhere—as Black Texans migrated in the decades following the U.S. Civil War. Juneteenth celebrations historically have featured parades and picnics, music, and barbecue—much like the July 4th holiday—the signing of hymns, the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, prayers, or other acts of thanksgiving.

Sunday Best Dress

According to the late William J. Wiggins Jr., a professor of African American and African Diaspora studies and a fellow with the Folklore Institute at Indiana University, “Juneteenth’s Sunday best dress code for its myriad rituals of rodeos, baseball games, barbecue and fried fish dinners, dances, and church programs was one of the most popular rituals used by the early celebrants to symbolize their new social status as free men and women.

Wiggins, a folklorist, added, “One informant summed up these sentiments well when he told me: ‘The 19th of June was just a second Christmas… everything… is especially set aside for that day. Even bought your new shoes, your new clothes, and dressed up.'”1

During the Jim Crow era, “White clothing merchants advertised early and often in such black Texas weekly newspapers as The Houston Informer in the hopes of cashing in on this Juneteenth clothes-buying spree.”

“Eating high on the hog”

In the 20th century, “Juneteenth picnic tables and baskets were a cornucopia of traditionally prepared dishes of meat, breads, vegetables, drinks, and desserts,” according to Wiggins. “Unlike their slave ancestors, emancipated Juneteenth celebrants could eat as much as they wanted; hunger did not dine at Juneteenth picnics. One celebrant recalled that her hometown Juneteenth committee served several hundred free picnic dinners featuring such traditional African-American dishes as barbecue chicken and ribs, potato salad, baked beans, mustard and collard greens, cornbread and red ‘soda’ water.”

Events and Excursions

Some of these holiday feasts were enjoyed after a train excursion ride to either visit friends and family or to make a freedom pilgrimage to Galveston, Texas, where General Granger had read his historical freedom decree. Railways advertised such special excursions in local newspapers. For example, one offer from the Santa Fe Railway in 1928 read:

“75 Minutes To Galveston. $1 Round Trip Sunday. Seaside Special Leaves Union Station 1:25 P.M. Arrives [in] Galveston 2:40 P.M. Morning Flyer leaves 8:05 A.M. Returning leave Galveston 8:25 P.M.”2

Similarly, the Missouri Pacific Lines in 1926 offered a $3 round trip excursion that would allow its customers to celebrate “Emancipation Day at Brazoria.”

The Separate Coaches Law of 1891, the first statewide segregation law instituted in Texas, made allowances for such excursions, allowing Blacks to ride in portions of the trains normally reserved for Whites—though only if the trains were hired out exclusively for the Benefit of Black travelers: “The provisions of this chapter shall not apply to any excursion train run strictly as such for the benefit of either race.”

Another popular destination in the mid-20th century was the Dallas Fair, which attracted enormous crowds in some years. “The 1951 ‘Juneteenth Jamboree’ attracted a crowd of 70,000 celebrants who spent $150,000 at the Fair riding the amusement rides, snacking at the food booths, and attending shows featuring nationally known African-American entertainers.”3

More local community gatherings typically involved church services, athletic events, and community meals.

History and Text of the Juneteenth Proclamation

Maj-Gen. Granger’s declaration came the same day federal troops arrived in Galveston, following weeks of looting and disorder after the collapse of Confederate authority in Texas. Confederate troops in the state had disbanded in May after news that Confederate armies in the East had surrendered.

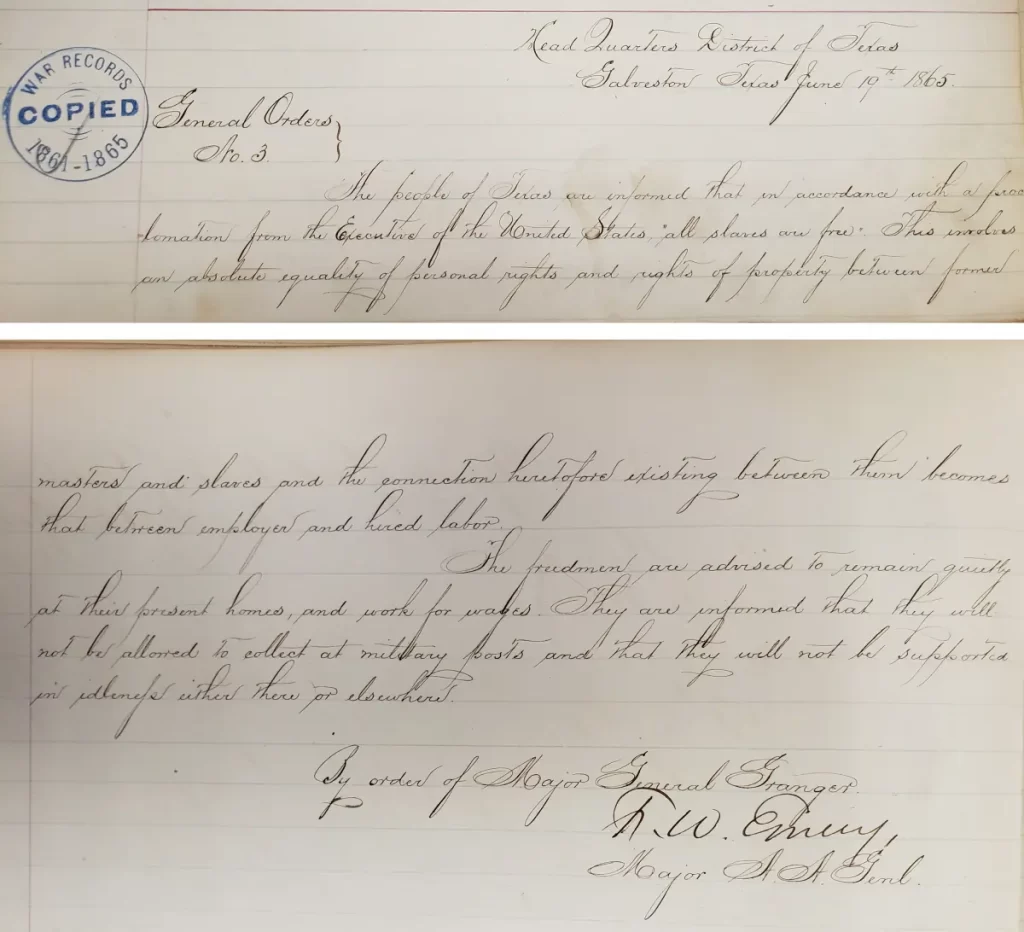

The original Juneteenth proclamation is preserved in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The heading says “General Order No. 3,” because it was the third general order issued by Granger after he arrived in Texas.

The order is handwritten by the general’s aide, F.W. Emery, and bears his signature. It reads:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

Controversially, Granger added, “The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Criticism of the Juneteenth Proclamation

Even though the Juneteenth proclamation freed slaves in Texas, it left them with the dilemma of how to start new lives with little or no possessions in a war-shattered land. Most slaves had grown up in bondage with no schooling or training for skilled trades.

Some observers have criticized the language used in the order. Michael Davis, a public affairs specialist for the National Archives, wrote, “While the order was critical to expanding freedom to enslaved people, the racist language used in the last sentences foreshadowed that the fight for equal rights would continue.”4

Sources Cited

- William H. Wiggins, “Juneteenth: A Red Spot Day on the Texas Calendar,” in Juneteenth Texas: Essays in African-American Folklore, ed. Francis Edward Abernethy (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 1996), 237–254. ↩︎

- The Houston Informer, June 16, 1928. ↩︎

- Wiggins, pg. 243. ↩︎

- Michael Davis, “National Archives Safeguards Original ‘Juneteenth’ General Order,” National Archives News, June 19, 2020, https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/juneteenth-original-document. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- The Juneteenth Story (Illustrated Children’s Book)

- The Juneteenth Cookbook: Recipes and Activities for Kids and Families to Celebrate

- Remembering the Days of Sorrow: The WPA and the Texas Slave Narratives

- On Juneteenth (Pulitzer Prize Winning Book)

- The History of Juneteenth: A History Book for New Readers

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.