After the Battle of San Jacinto, Texan separatists held the President of Mexico as a prisoner of war. General Antonio López de Santa Anna—both the head of state and the defeated commander of Mexico’s army—remained in Texan custody as the young republic sought diplomatic recognition and military security.

On July 4, 1836, Santa Anna addressed a letter to U.S. President Andrew Jackson, appealing for American assistance in securing peace and, implicitly, his release from imprisonment. The letter shows a conciliatory Santa Anna—once feared in Texas—now trying to present himself as a man of reason and peace.

President Jackson responded two months later with a carefully worded reply. While reiterating America’s policy of non-intervention, Jackson expressed sympathy for the humanitarian aim of peace and acknowledged the uncertainty surrounding Santa Anna’s political authority and treaties he had signed in captivity.

Though restrained in tone, Jackson’s letter also hints at deeper political dynamics. At the time of writing, his administration was already quietly encouraging Santa Anna’s eventual release—a move intended to calm tensions, avert renewed fighting, and clear the path for U.S. recognition of Texas.

Read together, these two letters offer a window into the diplomacy that accompanied the end of the Texas Revolution.

The exchange between Antonio López de Santa Anna and President Andrew Jackson occurred in the wake of a failed Mexican military campaign.

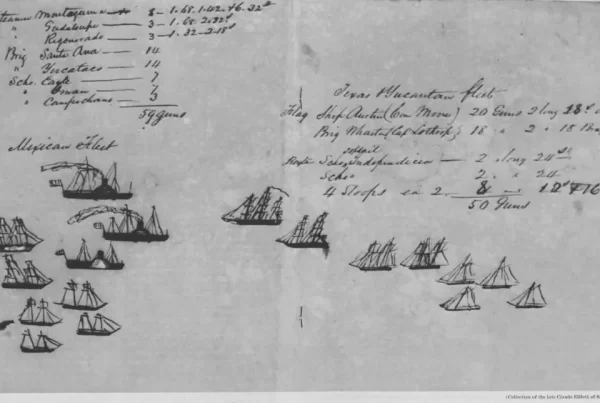

While the Texan army had routed Santa Anna’s forces at the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836 and taken the Mexican president prisoner, the war itself remained unresolved. Mexico refused to recognize Texan independence, and its forces still threatened to return. The future of Texas—whether as a republic, reabsorbed province, or annexed U.S. territory—remained very much in doubt.

Santa Anna’s capture immediately raised a dilemma for the new Republic of Texas. Some Texans, outraged by the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad, demanded his execution. Others, including Sam Houston, viewed him as a bargaining chip—useful for securing Mexican withdrawal, stabilizing the region, or even negotiating recognition. The Treaties of Velasco, signed in May while Santa Anna was in custody, reflected the latter approach. But Mexico soon disavowed the agreements, arguing that a prisoner of war lacked the authority to make binding commitments.

Despite the uncertainty, Texas’s interim government attempted to send Santa Anna back to Mexico in June 1836 aboard the schooner Invincible, believing his return could help fulfill the terms of the Velasco agreements. But public outrage—particularly among soldiers—forced the ship to return, and Santa Anna was placed again in close confinement. Still hoping to secure a negotiated peace and restore his reputation, he wrote directly to President Andrew Jackson on July 4, appealing for U.S. mediation.

Jackson, though sympathetic to Texas and closely tied to Sam Houston, was constrained by diplomatic realities. Formal U.S. involvement risked war with Mexico, and domestic opinion remained divided over the potential annexation of Texas. His reply, dated September 4, 1836, emphasized neutrality and humanitarian concern, while carefully avoiding recognition of either Santa Anna’s authority or Texan independence. Nonetheless, Jackson’s administration quietly supported de-escalation and began laying the groundwork for recognition.

Santa Anna remained a prisoner for several more months before being released in early 1837. He traveled through the United States under light supervision, meeting briefly with Jackson in Washington before departing for Havana. On March 3, 1837—one day before leaving office—Jackson formally recognized the Republic of Texas.

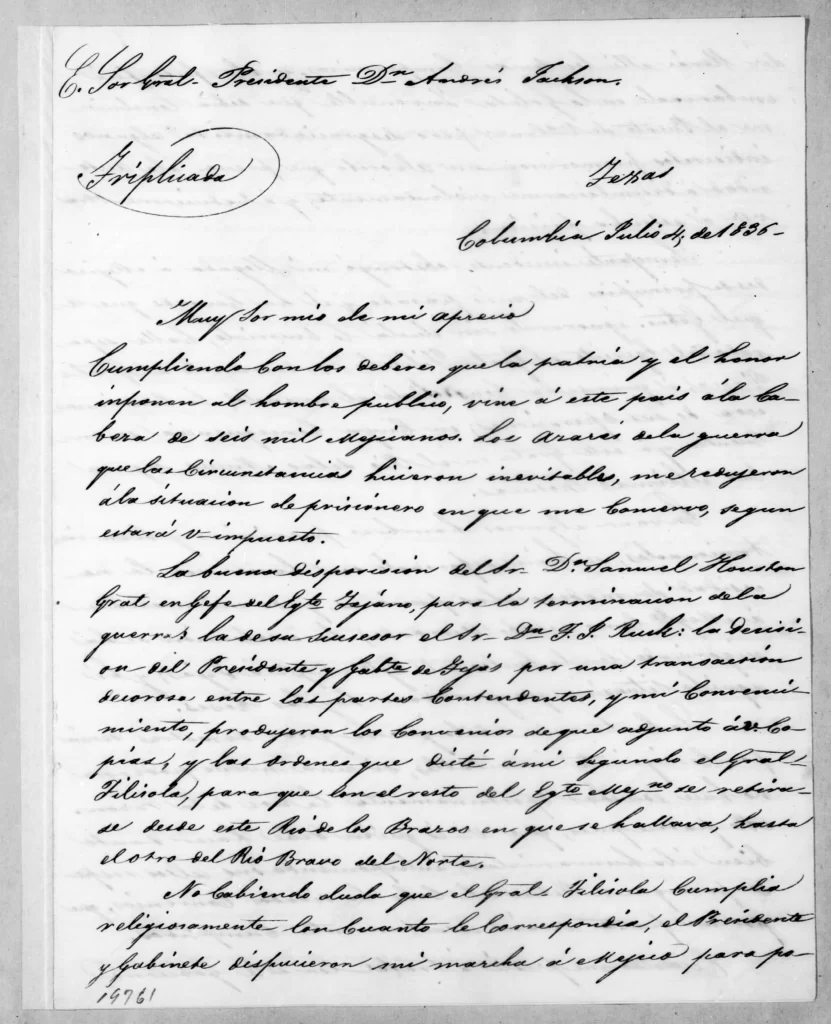

His Excellency the Hon. President Don Andrew Jackson

Columbia, Texas, July 4, 1836.

Regarded Sir, In fulfilment of the duties which a public man owes to his native country and to honor, I came to this soil at the head of six thousand mexicans. The disasters of war which circumstances rendered inevitable have reduced me to the situation of a prisoner, in which I still remain, as you will no doubt have been informed.

The good disposition manifested by Don Samuel Houston, Commander-in-chief of the Texian Army, for terminating the war, and by his successor, Don Thomas J. Rusk; the determination of the President and cabinet to make an honorable arrangement, between the contending parties, and my conviction; have given rise to the agreements, of which, I annex copies, as also of the orders issued by me to General [Vicente] Filisola, my second in command for him to retire with the remainder of the Mexican Army, from this river Brazos, where he then was, to the other side of the river Bravo del Norte.

As there was no doubt that General Filisola would scrupulously fulfill all that part, which related to him, the President and cabinet had taken measures for my return to Mexico, to enable me to complete the other stipulations, and I had, in consequence embarked on board the Schooner Invincible , which was to convey me to the Port of Vera Cruz, but it unfortunately happened that some indiscreet persons raised a tumult, which obliged the authorities forcibly to land me and again to place me in close confinement.

That incident prevented my arrival at Mexico, since the beginning of last month, which has induced that government, ignorant, no doubt of what had occurred, to take the command of the Army from General Filisola, ordering General [José] Urrea, to whom the command has been given, to go on with his operations, in virtue of which, the latter General is now at at the river Nueces, according to last accounts. In vain have some men of foresight and well-disposed, endeavoured to show the necessity of repressing the passions and of my return to Mexico, as it was agreed upon.

The excitement has gathered strength with the return of the Mexican Army to Texas. Such is the present state of affairs. The duration of the war and its disasters are therefore necessarily inevitable, unless a powerful hand interpose to cause the voice of reason to be opportunely listened to. It appears to me, then, that it is you who can render so great a service to humanity, by using your high influence to have the aforesaid agreements carried into effect; which, on my part, shall be punctually fulfilled.

When I agreed to treat with this government, it was under the conviction, that for Mexico to continue the war was unnecessary. I have acquired correct information of this country, of which, I was ignorant four months back. I am sufficiently zealous of the interests of my country, not to wish for her, that which is most suitable. Always ready to sacrifice myself for her glory and welfare, I would not have hesitated to prefer suffering torments or death, rather than consent to any arrangement whatever, if by such conduct an advantage had accrued to Mexico. My full conviction that it is more expedient to settle the present question by political negotiations, is, finally, the sole motive, which induces me to agree sincerely to what has been stipulated. In the same manner, do I make to you this frank declaration.

Be pleased then to favor me with like confidence, afford me the satisfaction of preventing evils near at hand, and of contributing to do the good, which my heart dictated. Let us establish mutual relations, to the end that your nation and the Mexican, may strengthen their friendly ties, and both engage amicably in giving existence and stability to a people that wish to figure in the political world, in which they will succeed, within a few years, with the protection of the two nations.

The Mexicans are magnanimous when treated with consideration. I will make known to them, with purity of intentions, the reasons of conveniency and humanity, which require a frank and noble conduct, and I do not doubt they will adopt it, when conviction has worked upon their minds. This manifestation will convince you of the sentiments, which animate me, and of those with which I have the honor to be

Your very devoted, obt. servt. [Signed] Antonio López de Santa Anna

A true translation, Velasco, 8th July 1836 [Signed] Edward Gritten.

Source: Andrew Jackson Papers, Library of Congress Manuscript Division

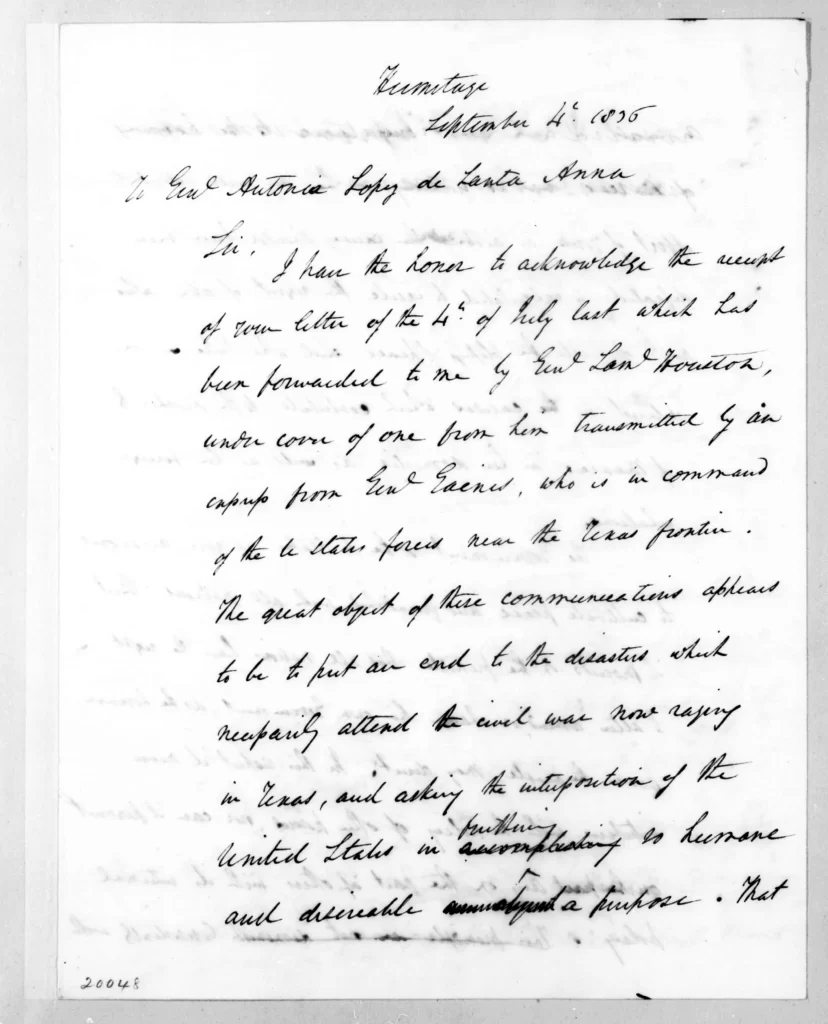

September 4, 1836 — The Hermitage, Tennessee

Sir,

I have the honor of acknowledging the receipt of your letter of the 4th of July last, forwarded by Genl. Samuel Houston, Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Republic of Texas, under cover of one from him, and transmitted by Genl. Gaines by express. The great object of these communications, on both sides, appears to be to put an end to the disastrous cruelties of the civil war now raging between Mexico and Texas, and asking the interference of the United States to aid in the accomplishment of so humane and desirable an object.

I sincerely regret to find from your letter that you have been prevented from carrying into effect the agreement with Texas by the indiscretion you have alluded to, when you had in view so desirable, humane, and beneficial results to both governments as the blessings of peace and a friendly intercourse between them, based upon the principles of a just reciprocity, so beneficial to both countries.

The Government of the United States are anxious to cultivate peace and friendship with all nations, and having adopted the principle that all nations have the right to alter, amend, and change their own government as the sovereign power—the people—choose, we never interfere with the policy of other nations nor permit them to interfere with our internal policy. But upon all occasions where our friendly interposition is asked to aid in restoring peace and tranquility to others, we freely yield it. But in the present case, we have been notified through the minister of Mexico that since your misfortune of being made prisoner, none of your agreements as President and commander of the Mexican government with the authorities of Texas would be recognized by the de facto government of Mexico, it being obvious your powers ceased with your capture.

Therefore, until the existing government of Mexico ask our friendly offices between the contending parties—Mexico and Texas—we cannot interfere. But should Mexico ask it, our friendly offices will, with pleasure, be afforded to restore peace and put an end to this inhuman warfare, whose acts of barbarity and massacre have occasioned every Christian people and humanity to shudder and condemn.

Your letter and that of Genl. Houston, Commander-in-Chief of the Texian Army, will be made the basis of an early interview with the Minister of Mexico at Washington. These communications will hasten my return to Washington, to which place I will set out in a few days and reach there by the first of October next. In the meantime, I hope Mexico and Texas will both find that war is one of the greatest evils, and will pause before another campaign can increase the evils which you were so anxious to avert.

I am respectfully yr. mo. obdt. servt.,

Andrew Jackson

Source: Andrew Jackson Papers, Library of Congress Manuscript Division

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| March 2, 1836 | Texas declares independence |

| April 21, 1836 | Battle of San Jacinto; Santa Anna captured |

| May 14, 1836 | Treaties of Velasco signed |

| July 4, 1836 | Santa Anna writes to President Jackson |

| September 4, 1836 | Jackson replies to Santa Anna |

| December 1836 | Jackson begins considering recognition of Texas |

| March 3, 1837 | U.S. formally recognizes Republic of Texas |

| May 1837 | Santa Anna released and returns to Mexico |

These letters, though diplomatic in form, reveal deeper currents at work. Santa Anna’s tone is calculated—he appeals to Jackson’s moral compass while preserving his own dignity, portraying himself as a reform-minded statesman rather than a defeated general. Jackson’s response, equally measured, maintains official neutrality but subtly signals support for peace on Texan terms.

At the time these letters were exchanged, Santa Anna’s fate remained deeply contested. A significant faction within the Texan leadership and public called for his execution, citing the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad as justification. Others, including Sam Houston, saw strategic value in keeping him alive—as a bargaining chip, a symbol of Texas’s military triumph, and a potential agent of de-escalation. The fact that Santa Anna was allowed to write Jackson at all, and that his letter was forwarded with Houston’s cooperation, reflects the influence of the latter view.

Behind the scenes, Jackson’s administration was already taking steps to encourage Santa Anna’s release and to lay the groundwork for recognizing the Republic of Texas. The language of both letters—focused on peace, reason, and humanitarian concern—disguises the geopolitical chess game unfolding just beneath the surface.

In effect, both men were using the language of diplomacy to shape outcomes far larger than themselves: the legitimacy of Texas, the stability of Mexico, and the trajectory of American expansion.

Santa Anna was ultimately released in February 1837 under orders from Texan authorities. He traveled to Washington, D.C., where he held a brief, symbolic meeting with President Jackson—carefully staged to avoid formal negotiations. Jackson reaffirmed his support for peace but maintained official neutrality. From there, Santa Anna departed for Havana and eventually returned to Mexico, where he re-entered national politics amid continuing turmoil. His captivity and this diplomatic exchange marked a turning point in both his career and the international status of Texas.

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.