The Texas House of Representatives is one of two parts, or chambers, of the Texas Legislature. Together with the Texas Senate, it makes laws and approves the state budget.

The Texas House of Representatives meets at the Capitol building in Austin. Though it is co-equal with the Texas Senate in many respects, the House is called the “lower chamber.”

The Texas House consists of 150 elected members. Each member serves a two-year term and the entire membership is up for reelection in even-numbered years.

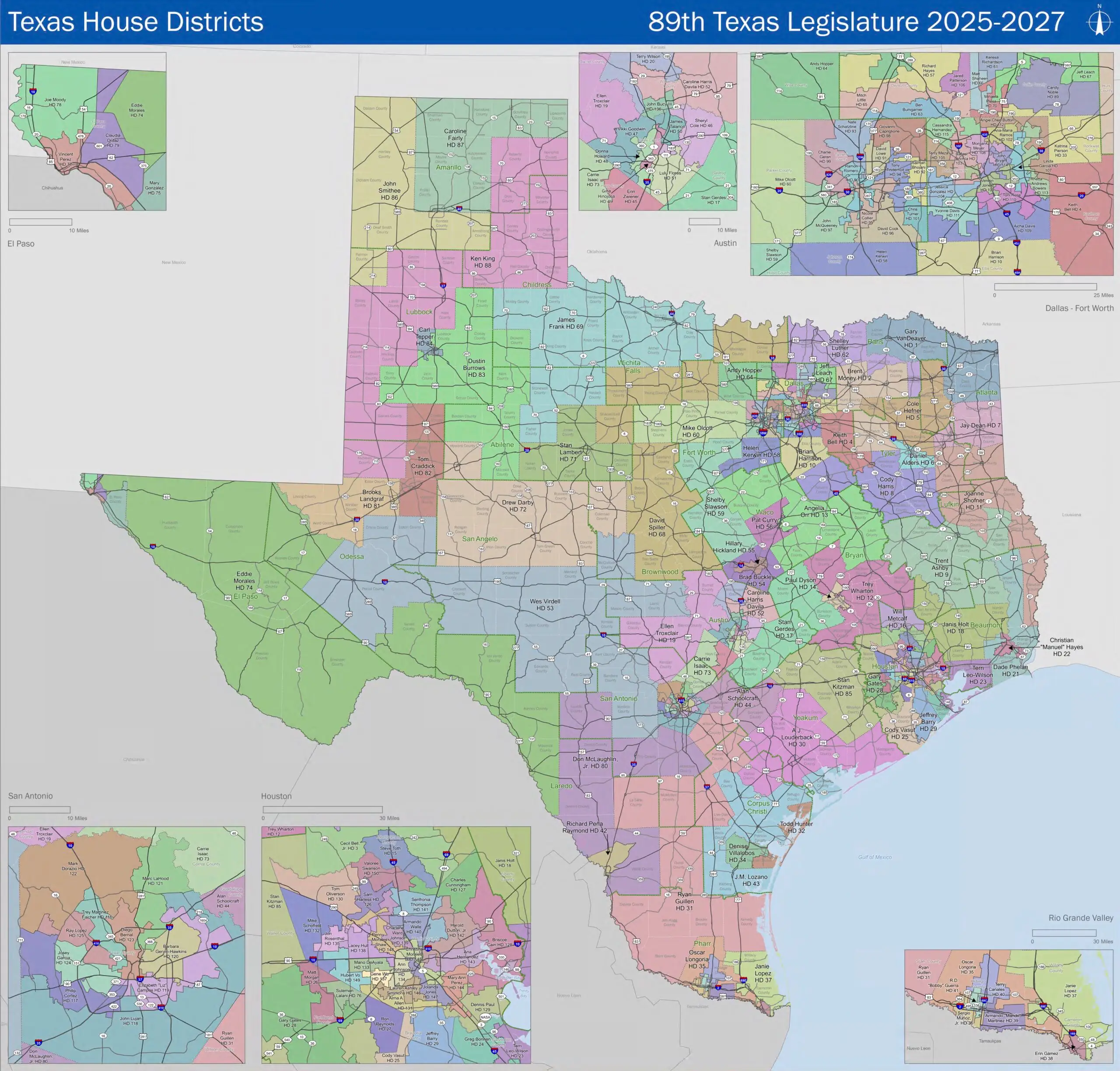

Members of the Texas House of Representatives are elected from geographic districts, the boundaries of which are drawn by the legislature itself.

- Term of Office: 2 years

- Constituents: Each member represents about 200,000 people.

- Last Election: November 5, 2024

- Next Election: March 3, 2026 (primary), November 3, 2026 (general)

Redistricting takes place every 10 years, adjusting the geographic boundaries of the districts to correspond with population changes.

The Texas House of Representatives has two principal officers: the Speaker, who is elected by the other members and wields considerable power, and the Speaker Pro Tempore, who fulfills a largely ceremonial function.

Unlike the U.S. House of Representatives, the Texas House does not formally recognize majority or minority leaders of different political parties, nor does it operate on a party-based system of committee chairs and ranking members. Instead, committee chairpersons and vice chairpersons may be appointed from either party.

The speaker’s duties include maintaining order within the House, recognizing members during debate, ruling on procedural matters, appointing members to the various committees and sending bills for committee review.

The administrative duties of the speaker include appointing chairpersons, vice-chairs, and members to each standing committee, appointing all conference committees, and directing committees to make interim studies.

The speaker pro tempore presides over the House during its consideration of local and consent bills, which are bills that generally are uncontroversial.

The chairpersons of committees preside over committee meetings where bills are considered at the early stage in the legislative process.

🟥 Republicans: 88 seats

🟦 Democrats: 62 seats

Republicans hold a 88-62 majority in the Texas House of Representatives, as of the 2025-2026 legislative session. There are no independent or third-party members.

Members are paid a salary of $600 per month, or $7,200 per year, plus a per diem of $221 for every day the legislature is in session. That adds up to $45,340 for a two-year term in which there is only one a regular session (140 days) and no special sessions. Legislators are eligible tor receive a pension after eight years, starting at age 60.

The members convene every two years for a five-month period, known as a regular session, plus for special sessions that may called by the governor during the interim between regular sessions. Because of the seasonal nature of this work, most members of the Texas House have another source of employment.

Under the state constitution, two-thirds of the members need to be present in the House chamber in order to conduct formal business.

If the House lacks quorum, a minority of members may vote for a ‘call of the House,’ a procedure that allows the sergeant-at-arms to lock the chamber doors and seek out and arrest absent members.

The constitution says, “Two-thirds of each House shall constitute a quorum to do business, but a smaller number may adjourn from day to day, and compel the attendance of absent members, in such manner and under such penalties as each House may provide.”

The Texas House employs staff in a variety of departments that serve the institution as a whole, including House Administration, House Business Operations, Legislative Operations, and the House Research Organization.

Additionally, each member of the Texas House typically hires several staff who work for that member alone, assisting the member in the performance of his or her duties. Staffers handle communications with constituents and stakeholders, help draft legislation, and give political advice. Common titles for legislative staff include chief of staff, legislative director, general counsel, policy aide, and district director.

House members who are committee chairpersons also supervise one or more committee aides who organize committee meetings, and who work for the committee as a whole.

Together with the Senate, the House oversees five external support agencies that are part of the legislative branch of government:

- Legislative Budget Board

- State Auditor

- Legislative Council

- Legislative Reference Library

- Sunset Advisory Commission

Administratively, these agencies are separate from the legislature itself but they work closely with legislators or their staff.

Redistricting in the Texas House of Representatives is a constitutionally required process conducted every ten years to adjust district boundaries in line with new U.S. Census data. The purpose is to maintain population equality among districts under the “one person, one vote” rule. The Texas Legislative Council, a nonpartisan support agency of the Legislature, plays a central role by supplying demographic analyses, legal guidance, and computerized mapping tools.

Once census data are delivered, the Legislature is responsible for enacting new maps during its regular session. If it fails to do so, the task shifts to the Legislative Redistricting Board, made up of five statewide officials: the lieutenant governor, speaker of the house, attorney general, comptroller, and land commissioner. The process operates under both state constitutional requirements and federal constraints such as the Voting Rights Act, which guards against the dilution of minority voting strength.

In recent decades, redistricting has been one of the most consequential and contentious exercises in Texas politics, dominated by the Republican majority since the early 2000s. GOP leaders have used control of the process to secure long-term partisan advantages, often drawing maps that consolidate suburban and rural districts while limiting the growing political influence of Texas’s expanding urban populations.

Courtroom showdowns defined past cycles but have yielded narrower remedies in recent years. After extensive 2011–2012 litigation that even forced interim court maps (Perry v. Perez), the U.S. Supreme Court in 2018 largely upheld Texas’s post-2010 plans, requiring changes to only one state House district (HD-90) while rejecting broader claims of intentional discrimination (Abbott v. Perez). And since 2019, the Court’s ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause has barred federal courts from policing partisan gerrymandering at all, pushing challenges to hinge mainly on race-based claims under the Voting Rights Act or the Constitution.

Litigation efforts have persisted in recent years, but they have not produced sweeping statewide changes to House lines. The cycle of high-stakes mapmaking, litigation, and political maneuvering has become a defining feature of the state’s legislative politics.