Slavery was a foundational institution of Texas from the establishment of the Austin Colony in 1821 until the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865. Slavery underpinned a plantation economy centered on cotton and sugar cane, and was justified ideologically by entrenched beliefs about the racial inferiority of people of African descent.

American settlers began bringing slaves into Texas while it was still part of Mexico, importing them primarily from Southern states such as Louisiana and Arkansas. Though the Mexican government banned the practice of slavery nationally in 1829, it tolerated it among the American settlers in Texas.

The 1836 independence of Texas and formation of the Republic accelerated the growth of slavery. By the time Texas joined the United States in 1845, slavery was firmly embedded in its economy, laws, and political identity—an alignment that deepened in the years leading up to the Civil War.

The rebellion of Texas and the other Southern states—intended to preserve slavery—ultimately led to its demise, following the military defeat of the Confederacy in 1865. If not for that fatal miscalculation, slavery might have lasted far longer.

Though Texans actively practiced slavery for only about 40 years, the legacy of slavery endured for another 100 years or more in the form of discriminatory Jim Crow laws, prevalent racist attitudes, and revisionist history about the supposed beneficence of the institution.

Slavery Under Spanish Rule

Under Spanish rule, slavery was legally permitted, but it operated within a different legal and moral framework than in the American South. Spanish law—including the Siete Partidas and later colonial ordinances—recognized slavery but also afforded certain limited rights to enslaved persons, including legal personhood, the right to marry, to own some property, and to purchase freedom.

Racial relations and concepts in colonial New Spain differed substantially from American ones. Although there were definite racial castes, associated loosely with social status, the caste system was never stable or totalizing; intermarriage was common, and there was no strict racial segregation of the kind later practiced by American settlers. Homogenizing influences in pre-independence Mexican society worked against racial stratification and segregation. In a study of neighboring New Mexico, Adrian Bustamante wrote,

“Colonial society possessed a mitigating element, acculturation, that worked against the [caste] system’s efficiency. Spain required every individual in the society to acculturate, i.e., speak the Spanish language, obey the same laws, adhere to Catholic beliefs, fight the same enemies, and exhibit other culturally standardizing behavior. As a consequence the real or ascribed cultural characteristics of each group (casta) were not sufficiently stable to persist in the close inter-ethnic contact that occurred on the frontier. As in other areas of New Spain, ethnic boundaries in New Mexico [and Texas] became blurred, causing the system to become muddled and largely ineffective. In fact… ecclesiastic and other officials had trouble in using the casta-categorizing nomenclature that gradually evolved.”1

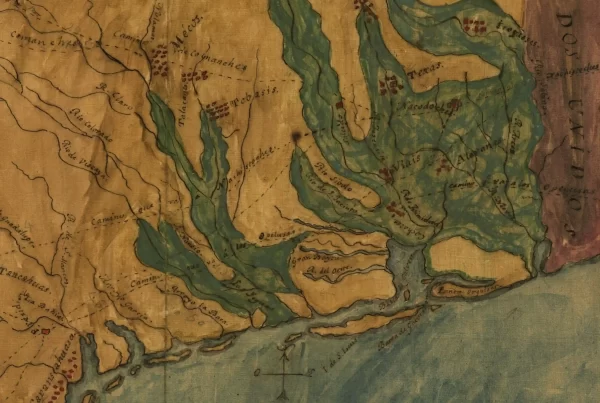

The Spanish census of 1777 reported only 20 Blacks in Texas (0.69% of the population), a figure that rose only to 42 (2.25%) by 1793.2 These figures may be an undercount, since mixed race residents were sometimes misclassified. One example of this is Antonio Gil Ibarvo, the founder and lieutenant governor of Nacogdoches, who is mentioned in census reports as a “Spaniard,” but was widely considered to be a “mulatto.” His racial status “did not prevent his becoming the most powerful person on the eastern frontier, or his accumulating considerable wealth.”3

Some Blacks arrived in Spanish Texas as slaves, while others came as escapees from French Louisiana or the United States. Still others were married to Frenchmen from Louisiana who had immigrated to East Texas after Louisiana came under Spanish rule in 1763.

“Most of the slaves were bought in New Orleans or in the French settlements along the Louisiana border by Texan cattlemen, who often used them as barter currency in their cattle business. Many fugitive slaves from Louisiana came as freemen to Texas… The census sheets frequently report Frenchmen married to or living with Indian, mestizo, mulatto, or Negro women.”

Alicia V. Tjarks, “Comparative Demographic Analysis of Texas, 1777-1793”

Most enslaved individuals in Spanish Texas were used in domestic service, ranching, or artisanal trades rather than plantation agriculture. Thus the practice of slavery in Spanish Texas differed from the later Anglo practice of slavery both economically and racially.

Slavery After Mexican Independence

The transition from Spanish rule to Mexican independence did not immediately eliminate the system of racial castes within Mexican society, including in Texas, nor coercive systems of labor, which remained in place on large haciendas in parts of the republic. Nonetheless, revolutionary and liberal ideas circulated among the Mexican elite, and some early Mexican leaders tried to restrict the practice of slavery.

In 1821, the new Mexican Congress passed a law in 1824 prohibiting the slave trade, but not slavery itself. Lawyers interpreted the law as a ban on the importation of slaves for resale; immigrants bringing slaves for their own use (not resale) were not affected, nor were existing slaves in Mexico emancipated. The lack of clarity and clear enforcement of the ban allowed American settlers to import slaves to Texas from neighboring Louisiana.

In 1829, President Vicente R. Guerrero, who was of Afro-Mestizo descent, issued a decree abolishing slavery. However, other officials stymied its implementation and Guerrero soon fell from power—partly as a result of political opposition to this decree. In Texas, Political Chief Ramón Músquiz withheld publication of the decree, but Texans learned of it anyway. Subsequently, Secretary of Relations Agustín Viesca wrote a letter clarifying that no change would be made respecting the slaves in Texas.4

Guerrero was deposed in December 1829 and the Mexican Congress passed a law cancelling his decree. His abrupt fall from power undercut the abolition movement in Mexico. He was captured and executed in 1831, after a brief civil war. Historian Jan Bazant has explained this development partly in racial terms; the execution served as a warning by the creole elite against persons of Indigenous and African backgrounds:

“Guerrero was of mixed blood and that the opposition to his presidency came from the great landowners, generals, clerics and Spaniards resident in Mexico… Guerrero’s execution was perhaps a warning to men considered as socially and ethnically inferior not to dare to dream of becoming president.”5

The defeat of Guerrero in 1831 thus resulted in the de facto toleration of slavery in parts of the Republic of Mexico until its final abolition in 1837. Nonetheless, the uncertain policy of the Mexican government toward slavery greatly worried slave owners in Texas, and became a contributing cause of the Texas Revolution.

“There was much dissatisfaction [among slave owners] over the uncertainty of legislation on the slavery question,” recalled Noah Smithwick, an early Texas settler.6 Due to this unease with the legal situation, during the 1830s, Anglo slavers increasingly brought slave to Texas under the legal fiction of “indentured servant” contracts.

Growth of the Slave Population in the Republic Era

After Texas won its independence from Mexico, the Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836) forbade free people of African descent from residing in the country without legislative permission and barred Congress from emancipating enslaved persons or preventing immigrants from bringing them into Texas. Enslaved people were considered chattel property, and slaveowners were guaranteed protection of their “right of property in slaves.”7

During the Republic period (1836–1845), the enslaved population in Texas grew rapidly. In 1836, the estimated number of enslaved persons was fewer than 5,000. By the final year of the Republic, the number had exceeded 30,000. Many enslaved people labored in cotton or sugar cane production in East Texas, though some were used for domestic work or hired out in towns.

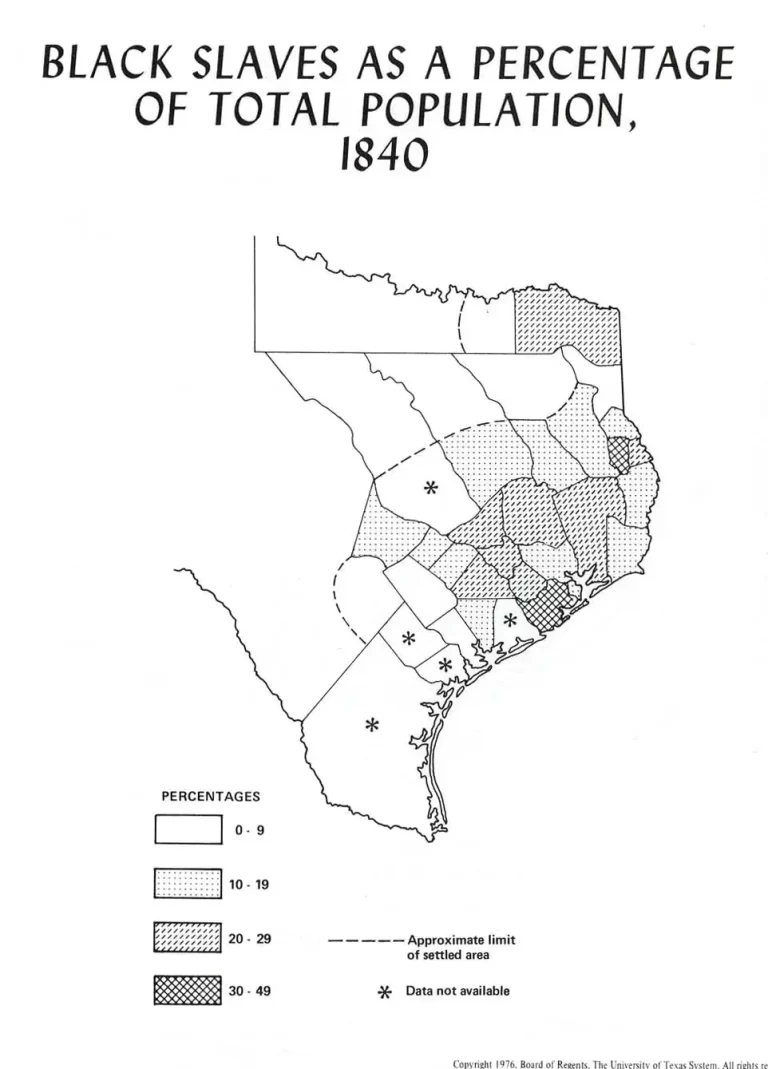

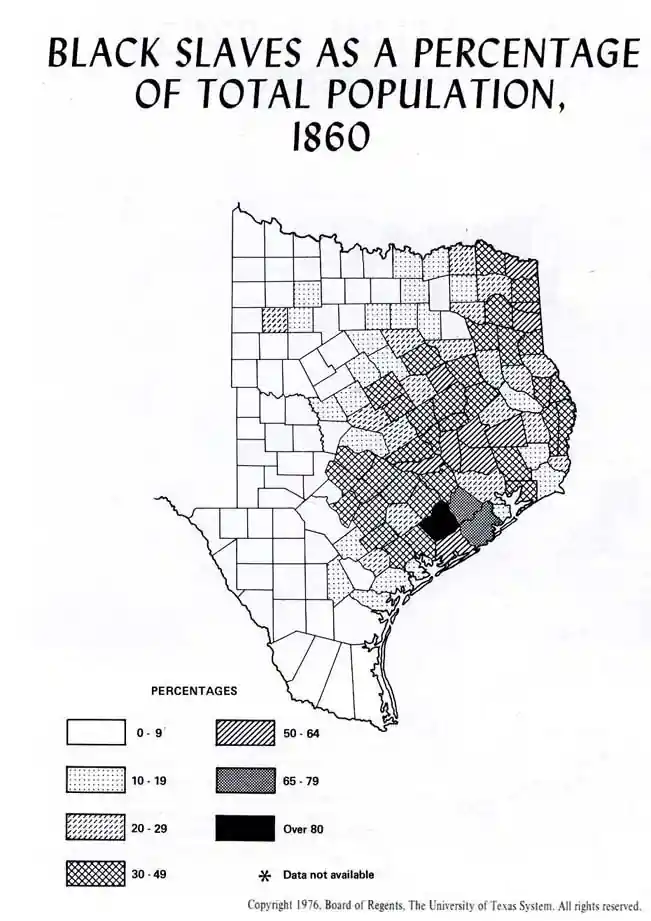

The proportion of slaves increased from about 12% of the total population in 1835 to about 27% in 1847, the year of the first census.8 The largest concentrations of slaves were on the plantations of the lower Colorado and Brazos rivers, and in scattered locations in East Texas. The annexation of Texas by the U.S. in 1846 accelerated the growth of the slave population:

“The slave plantation economy had a large expansion between 1835 and 1860, with the greatest increase coming in the first years of statehood. The older regions near the Gulf developed rapidly, as the existing planters spread out and took in more land, and new farmer-capitalists deserted already worn-out regions of the old South for Texas. The river bottoms of the entire coastal plains were devoted to cotton plantations.”

“The new area of expansion was in the deep northeast, along the Red [River]. Not gradually but explosively, like all American settlement of the last decades, the pine woods region was filled up with new plantations, and thousands more acres broken to the plot by black men. The farming, society, and outlook of this region, although it was rougher and had earmarks of a new frontier, were identical with the old South. Planters moved out of Mississippi and Georgia into east Texas without crossing any real frontier.”9

— T.R. Fehrenbach, historian and author of a bestselling 1968 history of Texas

As the planter class in Texas continued to grow in size and wealth in the 1840s and 1850s, they promoted racial ideas justifying the continuing enslavement of blacks. They drew on pseudo-scientific writings about race, passages of the Bible that mention slavery, classical literature, and other sources to counter abolitionist arguments circulating at the time. These ideas gained traction even among white Texans who did not own slaves.

Historian Carl H. Moneyhon sums up the prevailing view: “By 1860 most whites [in Texas] considered blacks to be an inferior people because of their race… By the time of the Civil War, most whites would have described blacks as lazy and shifty. At the same time, ironically, they viewed blacks as potentially violent. Such characteristics they considered as demanding that African Americans’ labor and behavior had to be controlled if they were to live in society with whites.”10

Conditions of Enslaved Persons

Though many enslaved Texans worked on large plantations, others lived on small to medium-sized farms, often with fewer than twenty enslaved people per owner. Field laborers typically rose before sunrise and worked long hours planting, tending, and harvesting cotton or corn. Meals consisted of simple fare—often cornbread, salt pork, and molasses—issued in rationed amounts by the owner. Clothing was coarse and issued seasonally, while medical care, when provided, was typically minimal and utilitarian.11

Despite harsh conditions, enslaved people in Texas sought to preserve family ties, spiritual traditions, and cultural practices. Many entered informal marriages, even though these had no legal standing. Children born to enslaved women were considered property of the owner, and family separations were common due to sales or inheritance.

Enslaved Texans developed religious communities that blended African spiritual traditions with Christian belief, often gathering secretly in woods or cabins for prayer meetings. Music, storytelling, and oral history played key roles in preserving collective identity and offering emotional resilience in the face of bondage.

Slavery in the 1845 State Constitution

Texas entered the Union in 1845 as a slave state. The U.S. annexation resolution explicitly allowed Texas to retain its public lands and guaranteed that slavery could continue unimpeded.12 The Constitution of 1845 echoed and expanded on the proslavery provisions of the earlier Republic charter. It prohibited the Legislature from passing laws emancipating enslaved people without the consent of owners and barred free Blacks from voting, holding office, or serving as jurors.

This constitutional entrenchment made Texas one of the most legally rigid slave states in the Union, reinforcing the role of slavery not just as an economic engine but as a defining legal norm.

The Political and Economic Role of Slavery

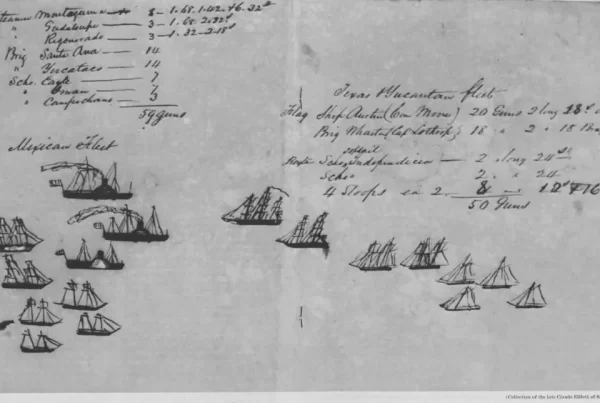

In the antebellum period, slavery became inseparable from Texas politics. Planters and slaveholders dominated the state legislature and used their power to ensure low taxes on slave property, strict patrol laws, and favorable land policies that encouraged the spread of cotton plantations. Slave labor fueled Texas’s entry into the global cotton market—particularly through ports like Galveston—and shaped settlement patterns in the fertile counties east of the Trinity River.

Efforts to expand slavery westward—particularly into the Hill Country and the Rio Grande valley—met with more resistance, both environmental and cultural. German immigrants in Central Texas, for example, often opposed slavery on moral and economic grounds, contributing to early divisions within the state.13

Even many American-born settlers farmed their own land, owned no slaves, and were “were alien, even hostile, to black servitude,” according to historian T.R. Fehrenbach. In his best-selling 1968 history of Texas, Fehrenbach explained how Texas was divided between a plantation society along the coast and in the east, and a small farm economy farther inland:

“Almost half the settled regions of Texas, extending beyond the river-bottom plantation belts, were populated by yeoman farmers, hill and forest men from the South. This area built a frontier farm economy and a frontier crop system very similar to that of the Midwest. The people who staked out their small farms along this great semicircle, reaching from Sherman-Denison in the north down to the vicinity of Austin, were alien, even hostile, to black servitude. The society was a rough, scattered one of distant small farms dotting the broad horizons… The people had a passion for the land and an everlasting bias against social organism.”

“Thus this region between the Sabine and the Gulf and the inland, rising plateau line, where antebellum settlement stopped, which was to become the heartland of the state, was already divided economically and socially between the two great divisions of the old South, the old plantation and the old frontier.”

“The coastal nucleus of Texas consisted of great plantations laid out among the moss-hung oaks along the broad, muddy rivers, where cotton grew splendidly in the mucky alluvial soils. Inland, where gently rolling post-oak belts and rich, blackland prairies began, the country was a series of log cabins and rough-hewed farm fences, enclosing fields of straggling corn.”

“Beyond the oak and prairie belt, where the horizons broadened into rising plateaus of low, flat, stony-soiled hills, and the enormous seas of grass began, the settlement dribbled out.”14

Census statistics confirm this geographic division: counties along the coast and river basins had thousands of slaves each, whereas counties situated in the inland plateaus, Hill Country, and prairies had only a few hundred or sometimes just a few dozens slaves.

Legal Framework and Policing

Slavery in Texas was regulated by a mix of state statutes and county-level enforcement. Enslaved persons could not legally marry, testify in court against White persons, own property, or leave their plantations without written permission. Resistance or escape attempts were punished with physical violence or sale to harsher conditions further east.

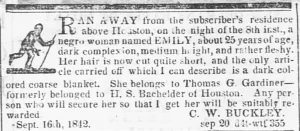

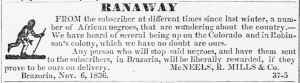

In many counties, “patrol laws” mandated that groups of White men regularly inspect enslaved quarters and suppress gatherings. Some counties issued formal rewards for the capture of runaways or published newspaper notices describing escaped persons in detail.

Texas law also required that manumissions—when permitted—occur only outside the state. Free persons of African descent were required to leave Texas within a specified time or face re-enslavement.

The Republic government levied a head tax on enslaved persons, and county-level censuses often counted them separately from free persons, reinforcing their legal status as property. Runaway slave laws were passed and enforced, and Texas negotiated fugitive slave treaties with nearby Indian nations.15

Resistance and Rebellion

Enslaved Texans engaged in quiet and overt forms of resistance, from work slowdowns and tool sabotage to escape and rebellion plots. One of the most notable fears among White Texans was the threat of a slave uprising. In 1860, amid sectional tensions, panic erupted in North Texas after a series of fires in Denton and other towns. White residents blamed abolitionists and enslaved people, leading to the execution of dozens of Black Texans without formal trial.16

Though often silenced in the historical record, the stories of resistance—of flight, rebellion, survival, and community formation—remain a crucial part of understanding slavery in early Texas.

Limits and Early Challenges to Slavery

Even in its heyday, slavery in Texas operated amid geographic limitations and cultural tensions. The state’s vastness and frontier conditions sometimes made enforcement difficult, giving slaves opportunities to escape or exercise limited freedoms.

Patrols were inconsistent beyond the river-bottom plantation belts, and many regions—especially in the post-oak uplands and blackland prairies—were settled by smallholding farmers who were indifferent or even hostile to Black servitude, favoring land ownership and personal independence over planter hierarchy. The resulting social landscape—log cabins and subsistence cornfields rather than great cotton estates—stood in contrast to the slaveholding society along the Gulf rivers.

Texas lacked a formal abolitionist movement, but antislavery ideas still circulated. German immigrants brought free-labor ideals, and some Tejano communities retained cultural opposition to slavery rooted in Mexican law. Northern newspapers and abolitionist literature also found their way into Texas despite legal prohibitions, subtly shaping attitudes in certain regions, particularly among literate, non-slaveholding Whites.

Geography itself undermined slavery’s hold. Mexico had abolished slavery in 1829, and slaves who could reach the Rio Grande sometimes found refuge. In practice, however, the journey to Mexico was arduous and dangerous, and few were willing to risk it. Noah Smithwick, an early Texas pioneer, recalled in his memoirs an incident in which a slave named Mose escaped to Mexico only to return voluntarily, saying he had “wearied of ‘husks’ [meager food].”17 He also related the story of a killing in connection with an attempted escape:

“The negroes soon became aware of the legal status of slavery in Mexican territory, and it was probably owing to their ignorance of the language [Spanish] and country that more of them did not leave. Jim, one of McNeal’s slaves, openly announced his determination to leave, and, acting on the impulse, threw down his hoe and started away. Pleasant McNeal, to whom he communicated his intention, ordered him to return to work, but Jim went on, whereupon Pleasant raised his rifle. ‘Jim,’ said he, ‘if you don’t come back I’ll shoot you!’ Jim, however, kept on and true to his threat McNeal shot him dead.”

The risks of death and destitution were enough to deter most slaves from leaving their masters.

Emancipation and the End of Slavery in Texas

At the height of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declaring all enslaved persons in Confederate territory to be free. In spite of this, Texas remained largely unaffected at the time due to its geographic isolation and continued Confederate control. In fact, the enslaved population in Texas actually grew during the war, as slaveholders from other Southern states drove tens of thousands of enslaved people westward to escape advancing Union troops.

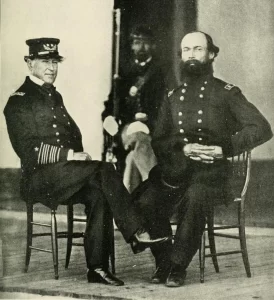

It was not until June 19, 1865, when Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston with federal troops, that emancipation was publicly enforced in Texas. Granger’s General Order No. 3 declared that “all slaves are free,” triggering celebrations among the Black population and the beginning of a long, uncertain transition to freedom. This date became known as Juneteenth, now observed as a state and federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery in Texas.

Full legal abolition came with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in December 1865, which formally outlawed slavery nationwide. For many formerly enslaved Texans, however, emancipation brought new forms of hardship, including Black Codes, forced labor contracts, and racial violence, shaping the difficult course of Reconstruction in the state. Economically, conditions changed only gradually, as many former slaveholders retained control of the same land and compelled freed people into sharecropping and tenant arrangements that perpetuated dependency and poverty well into the nineteenth century.

Sources Cited

- Adrian Bustamante, “The Matter Was Never Resolved: The Casta System in Colonial New Mexico, 1693–1823,” New Mexico Historical Review 66, no. 2 (April 1991): 144–145. ↩︎

- Alicia V. Tjarks, “Comparative Demographic Analysis of Texas, 1777-1793,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 77, no. 3 (January 1974): 291-338. ↩︎

- Tjarks, 326. ↩︎

- Robert Bruce Blake, “The Guerrero Decree: Abolishing Slavery in Mexico,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, first published 1952; last updated August 2, 2020, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/guerrero-decree. ↩︎

- Jan Bazant, “The Aftermath of Independence,” in Mexico Since Independence, ed. Leslie Bethell (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 12. Originally published in A Concise History of Mexico [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977]. ↩︎

- Noah Smithwick and Nanna Smithwick Donaldson, The Evolution of a State, or, Recollections of Old Texas Days (Austin, TX: Gammel Book Company, 1900), 37. ↩︎

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836), General Provisions ↩︎

- William Ransom Hogan, The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1946), pg. 20. ↩︎

- T. R. Fehrenbach, Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (1968; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 2000), pg. 285 ↩︎

- Carl H. Moneyhon, Texas after the Civil War: The Struggle of Reconstruction, vol. 14 of Texas A&M Southwestern Studies (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004), 15. ↩︎

- Randolph B. Campbell, An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821–1865 (Louisiana State University Press, 1989). ↩︎

- Joint Resolution for Annexing Texas to the United States, 28th U.S. Congress, 1845.

Constitution of the State of Texas (1845), Article VIII. ↩︎ - Terry G. Jordan, German Seed in Texas Soil: Immigrant Farmers in Nineteenth-Century Texas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1966). ↩︎

- T. R. Fehrenbach, Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (1968; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 2000), 286. ↩︎

- Texas Laws, Acts of the Republic, 1837–1845 ↩︎

- Carl H. Moneyhon, “The Texas Troubles of 1860,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 86 (1982). ↩︎

- Noah Smithwick and Nanna Smithwick Donaldson, The Evolution of a State, or, Recollections of Old Texas Days (Austin, TX: Gammel Book Company, 1900), 37. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands

- Texas Slave Narratives & Photographs

- The Laws of Slavery in Texas

- Slavery and Freedom in Texas: Stories from the Courtroom, 1821-1871

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.