From 1919 to 1935, the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages were illegal in Texas under a combination of federal and state laws. Though the state had long been a stronghold of the temperance movement, Prohibition exposed deep divisions in Texas politics and society—between urban and rural voters, immigrants and native-born Texans, and reformers and lawmen on one side, bootleggers and drinkers on the other. The period saw the expansion of state police power, the erosion of public trust in enforcement, and the eventual collapse of the idealistic promise of a sober society.

Roots of Reform

By the time national Prohibition arrived, Texas already had a long history of regulating alcohol. As early as the 1840s, local-option laws allowed counties and municipalities to vote themselves dry. These measures expanded in the 1880s and 1890s, propelled by Baptist and Methodist activism, women’s organizations, and rural reformers. By 1910, more than 200 counties in Texas had banned saloons through local elections.

The state came close to full prohibition in 1911, when voters narrowly rejected a constitutional amendment to ban alcohol statewide. That defeat, however, energized the temperance movement. In 1918, amid wartime patriotism and growing support for national reform, Texas ratified the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transport of intoxicating liquors.

Texas Joins the National Ban

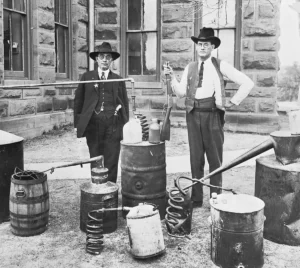

National Prohibition took effect in January 1920, enabled by the federal Volstead Act. But Texas had already passed its own enabling statute—often called the Dean Act—which took effect in 1919 and prefigured the national ban. These laws empowered both state and federal officers to arrest violators and seize property used in the production or sale of alcohol. The Texas law imposed stricter penalties than the federal one, tearing violations as felonies rather than misdemeanors. However, it defined intoxicating liquors less strictly, as those having one percent or less of alcohol, rather than the 0.5 percent threshold in the federal law.

Governor William P. Hobby and the Texas Legislature supported Prohibition strongly in its early years. Enforcement responsibilities were divided among local sheriffs, Texas Rangers, and newly assigned federal agents. In 1923, the state created the Texas Liquor Control Board to coordinate enforcement, though it remained poorly funded and politically vulnerable.

Enforcement and Resistance

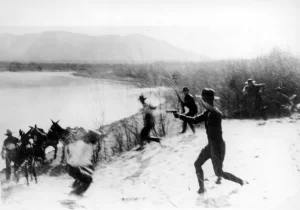

The letter of the law stood in stark contrast to public behavior. Moonshine operations flourished in East Texas and the Hill Country, while organized smuggling rings operated along the Gulf Coast and the Rio Grande. Speakeasies and private clubs emerged in major cities such as Houston, Dallas, and Galveston. Though arrests were common, convictions were not. Juries were often sympathetic to defendants, and local officials frequently looked the other way.

Corruption became endemic. Some law enforcement officers, including Texas Rangers, were implicated in taking bribes or participating in illegal alcohol distribution. In response, temperance groups pushed for stricter penalties, while critics called for a reevaluation of the entire system.

The period also saw a disproportionate impact on immigrants and minority communities. Ethnic Germans and Mexican Americans were more likely to brew or consume alcohol as part of cultural traditions and were often targeted in raids. Non-compliance in the Rio Grande Valley was widespread, and much smuggling took place across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Political Fallout

Prohibition became a defining issue in Texas politics during the 1920s and early 1930s. “Dry” candidates aligned with evangelical churches and rural populism, while “wet” factions gained support in urban areas and among business interests. The state’s Democratic Party remained officially dry through most of this period, though internal divisions widened as enforcement faltered and public support declined.

By the early 1930s, Texans—like much of the country—had grown disillusioned. The Great Depression intensified calls for repeal, both to reduce government spending on enforcement and to allow taxation of alcohol sales. Legalizing alcohol was seen not only as a social correction but an economic recovery measure.

Repeal and the Aftermath

The national Prohibition regime ended with the ratification of the 21st Amendment in December 1933. Texas voters supported repeal, and the state convened a special convention to formally approve the amendment.

Even so, alcohol remained illegal in Texas under state law until 1935, when voters passed a constitutional amendment repealing statewide prohibition. The Legislature then created the Texas Liquor Control Board (now the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission) to regulate and license alcohol sales moving forward.

Texas retained a patchwork of local-option laws. Many counties and towns chose to remain dry, and even today, remnants of that system persist in local ordinances and zoning restrictions across the state.

Legacy

Prohibition in Texas left behind a mixed legacy. It reflected a strong current of moral reform that had long animated state politics, particularly in rural and religious communities. But it also revealed the limits of law when public sentiment diverges from official policy. The era expanded state regulatory power while undermining respect for it, setting the stage for later debates over personal liberty, criminal justice, and public order.

Though officially ended in 1935, the political and cultural arguments that fueled Prohibition in Texas continued to shape debates over alcohol, drugs, and government enforcement well into the modern era.