Revolutionary Sparks in Spanish Texas

By the early 1810s, Spain’s grip on its American colonies was weakening. The Peninsular War in Europe had disrupted royal authority, and revolts were spreading across New Spain. In Texas—a distant, underpopulated province—discontent simmered among Tejanos and others who resented centralized Spanish rule and the lack of local autonomy. Some saw the chaos as a chance to break free.

In the early 1810s, the Spanish Empire was under pressure across the Americas. Revolutionary uprisings in Mexico—led by figures like Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos—stirred unrest among border populations in Texas.

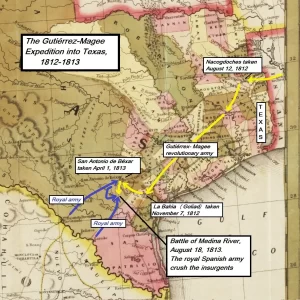

In 1812, a coalition of Mexican revolutionaries and filibusteros (mercenary soldiers or adventurers) crossed into Spanish Texas with the goal of ousting royalist forces and establishing a republican government. Their efforts, known collectively as the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition, would briefly upend Spanish control but ultimately end in disaster at the Battle of Medina, the bloodiest engagement ever fought on Texas soil.

The expedition was named after its two original leaders: José Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, a Mexican insurgent and diplomat aligned with independence forces in northern Mexico, and Augustus Magee, a former U.S. Army lieutenant.

U.S. Involvement and Cross-Border Origins

Though part of the Mexican independence effort, the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition was organized in the United States. In 1811, Gutiérrez traveled to Washington, D.C., to request American aid in Mexico’s independence war but was unsuccessful. Instead, he turned to private American citizens in Louisiana who were sympathetic to his anti-royalist cause.

He found allies among U.S. frontiersmen and adventurers—many of whom had military experience from the War of 1812 and saw opportunity in the political instability of New Spain. Magee, frustrated with the U.S. Army and inspired by revolutionary ideals, agreed to lead the military campaign into Texas.

Gutiérrez’s partnership with former U.S. Army officer gave the campaign its military structure. Together, they organized a force of Anglo-American volunteers and Tejano sympathizers in Natchitoches, Louisiana, and launched the invasion from the U.S. side of the Sabine River. Although the United States government maintained formal neutrality, its enforcement was inconsistent. Local officials often looked the other way, and some Americans openly viewed the expedition as a way to encourage the spread of republican ideals—or American influence—into Spanish Texas.

The expedition’s origins on U.S. soil, combined with its makeup of both Anglo and Mexican fighters, gave it the character of a cross-border republican venture. This blending of causes would foreshadow the recurring entanglement between American filibusterers, frontiersmen, local Tejanos, and rebel Mexican politicians in the decades to come.

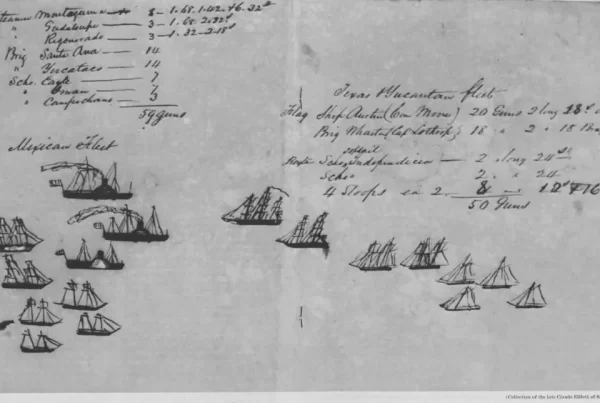

The Republican Army of the North

Crossing into Texas in August 1812, the expedition—calling itself the Republican Army of the North—captured Nacogdoches and then advanced through Goliad, taking the Presidio La Bahía after a prolonged siege.

After Magee died of illness early in the campaign, command passed to Samuel Kemper, another American adventurer. Royalist Spanish forces attempted to dislodge the insurgents in a prolonged siege at Goliad, but the Republicans held firm. The conflict escalated in early 1813 when the republican army advanced toward San Antonio and ousted Spanish officials from the city.

In April 1813, Gutiérrez issued a declaration of independence for Texas and a short-lived republican constitution, claiming sovereignty over the province in the name of Mexican independence. This moment marked one of the earliest attempts to establish an independent government in Texas—a precursor to the later Republic of Texas.

The new regime, however, was shaky from the start. Tensions flared when Spanish officials captured in San Antonio were executed, likely with Gutiérrez’s approval. The executions shocked many of the American volunteers, who soon withdrew from the expedition in protest or disillusionment.

Victory and Collapse at the Battle of Medina

In response to the rebellion, the Spanish government dispatched a royalist army under General Joaquín de Arredondo, a seasoned commander determined to crush the insurgents. In August 1813, the two forces met south of San Antonio near present-day Atascosa County in what became known as the Battle of Medina.

The Republican Army, now led by José Álvarez de Toledo y Dubois, had reorganized but remained disunited. Arredondo’s troops feigned retreat and lured the Republicans into a trap. What followed was a massacre: between 1,000 and 1,300 revolutionaries were killed, making it the bloodiest battle in Texas history. Survivors were hunted down, and Arredondo imposed a brutal campaign of retaliation that devastated local communities suspected of supporting the rebellion.

In the aftermath, Spanish control over Texas was restored with severe repression. Gutiérrez had already withdrawn from leadership, and the broader Mexican War of Independence would continue for another eight years without significant revolutionary activity in Texas.

Legacy in Texas Political Memory

Although the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition ultimately failed, its political and symbolic impact endured. It was the first organized military campaign to challenge Spanish rule in Texas with the goal of establishing a republican government. The short-lived Republic of the North, despite its collapse, set a precedent for the idea that Texas could exist as a self-governing territory—an idea that would reemerge in the 1830s.

The Battle of Medina, once little known, has received growing attention as a formative moment in Texas history. Commemorations and scholarly reassessments have emphasized both the scale of the conflict and the diverse composition of the Republican Army. Mexican revolutionaries, American filibusters, Tejanos, and African Americans fought side by side in an early and chaotic effort to redefine the political future of the region.

The expedition also exposed the limits of revolutionary cooperation in a frontier setting. While united in opposition to Spain, the participants held diverging views on governance, justice, and legitimacy. The internal fractures of the movement foreshadowed later tensions in Texas political life, including debates over slavery, loyalty, and military authority.

Though largely overshadowed by the better-known Texas Revolution of 1836, the events of 1812–1813 remain a foundational chapter in the state’s revolutionary tradition. The Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition showed that rebellion in Texas was possible—but also that premature revolution without unity or preparation could invite catastrophic defeat.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Forgotten Battlefield of the First Texas Revolution: The Battle of Medina, 1813

- The Mexican Wars for Independence: A History

- The Wars of Spanish American Independence 1809–29

- History of the American Frontier: 1763-1893

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.