Historical Context

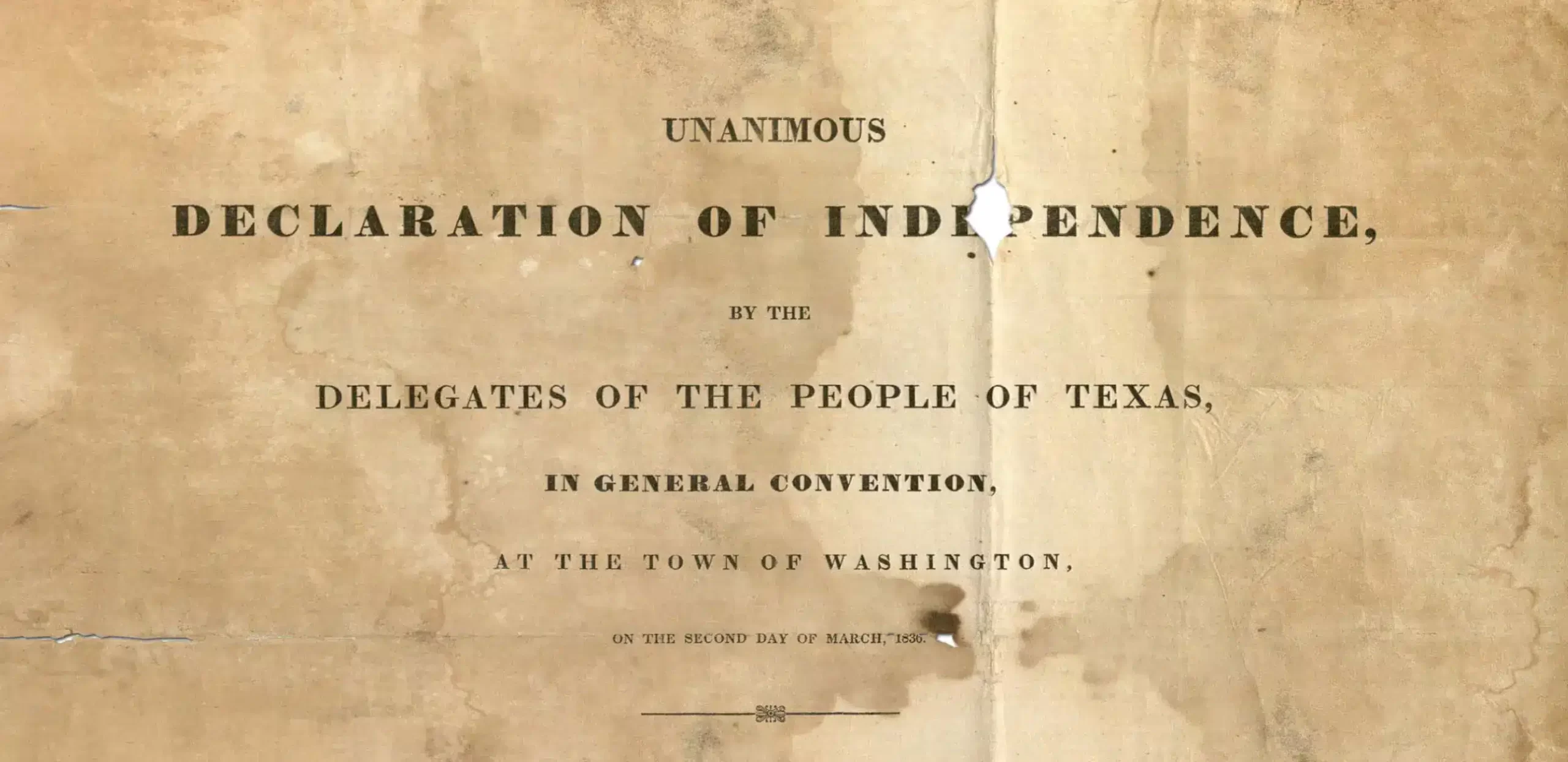

The Texas Declaration of Independence, adopted at Washington‑on‑the‑Brazos on March 2, 1836, formally severed ties with Mexico and proclaimed the creation of a sovereign Republic of Texas. The document drew heavily on the philosophical language of the United States Declaration of Independence, asserting the right of revolution in response to governmental tyranny. It accused the Mexican government under General Antonio López de Santa Anna of centralizing power, dismantling the federalist Constitution of 1824, and violating the political and civil rights of the Anglo-American settlers who had been encouraged to colonize Texas under earlier Mexican law.

Though adopted in the midst of military crisis—just days before the fall of the Alamo—it marked the birth of Texas as an independent republic. Within days, the same convention adopted the Republic’s constitution, establishing a new government that would last until Texas’ annexation by the United States a decade later.

The declaration was signed by sixty men. Most of the signatories were U.S.-born Anglo settlers, while three were Hispanics—two native-born Texans (José Antonio Navarro and José Francisco Ruiz) and one, future vice president Lorenzo de Zavala, who was born elsewhere in Mexico. This composition reflected the decade-long influx of Anglos into Mexican Texas, alongside an enduring Tejano political presence. Although outnumbered, the participation of these prominent Hispanic figures underscored that resistance to Santa Anna’s centralization was a shared concern, uniting diverse communities in support of independence.

Texans adopted the declaration only after months of debate over whether to declare independence or support the Federalist faction within Mexico. According to historian James K. Greer, “The winter of 1835-’36 saw public opinion in Texas crystallize toward the belief that the time had arrived for Texas to sever its relation with the Mexican government. Hope that the Mexican Liberals would assist the Texans in a future safeguarding of their rights had dwindled; a declaration on November 7, 1835, in favor of the Mexican constitution of 1824 had repelled Americans and failed to secure support from Mexico.”

“Even Stephen F. Austin, the colonist most loyal to the Mexican government in Texas, who had said in November, 1835, that Texas had ‘legal and equitable and just grounds to declare independence,’ but continued to insist on strict adherence to the Mexican Federal Union during the same period, finally said that he was now in favor of an immediate declaration of independence. Having arrived at this conclusion, Austin now threw all his influence (and it was of great weight with the people as a whole) to securing unity of the people in favor of a declaration of separation from the Mexican government.”1

On February 1, 1836 an election of delegates to the convention was held in the various municipalities of Texas. They assembled on March 1, 1836 and appointed a committee to draft a Declaration of Independence, consisting of George Childress of Milam, James Gaines of Sabine, Edwin Conrad of Refugio, Collin McKinney of Red River, and Bailey Hardeman of Matagorda.

Childress, a Nashville-trained lawyer and former newspaper editor, who had only recently arrived in Texas, is widely recognized as the principal author of the declaration. The drafting committee completed its work in a single day—strong evidence that Childress arrived at the convention with a draft already in hand. A newspaper memorial for his brother Wyatt even recounts that Childress composed the original draft in his brother’s blacksmith shop, lending a vivid, frontier-era detail to the declaration’s origins.

Full Text of the Texas Declaration of Independence

Note: Headings added for readability. The original document was written as a continuous statement without formal sections.

- James K. Greer, “The Committee on the Texas Declaration of Independence,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 30, no. 4 (April 1927): 239–40. ↩︎

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic by purchasing any of these handpicked titles:

- Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence

- Women and the Texas Revolution

- Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836

As an Amazon Associate, Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.