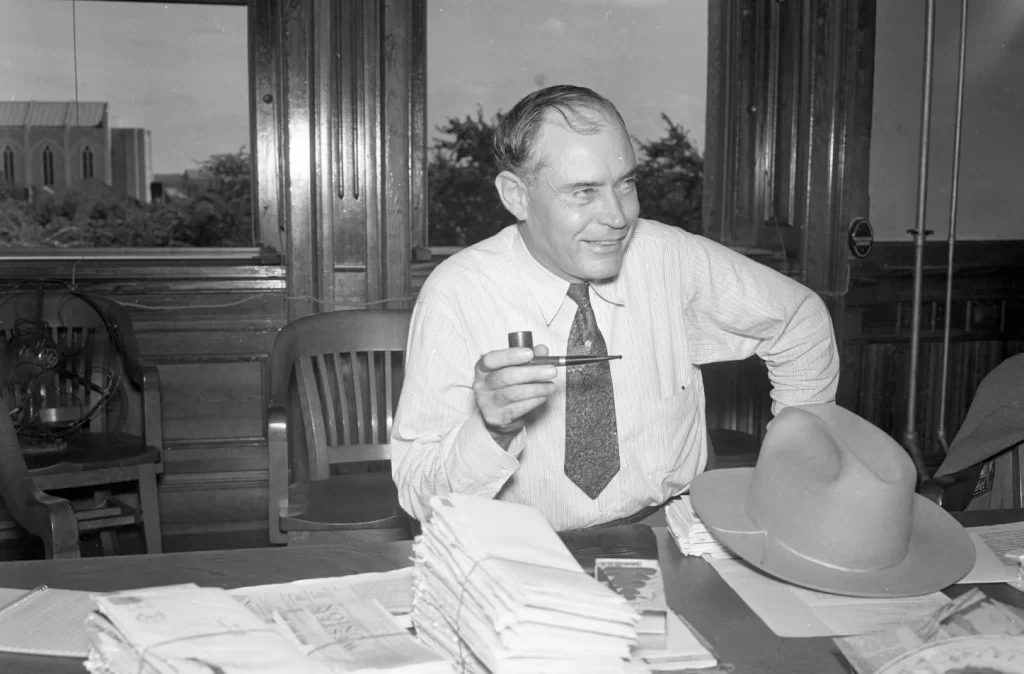

Coke R. Stevenson (1888–1975) served as the 35th Governor of Texas from 1941 to 1947, a period of national mobilization and federal expansion in response to World War II. A moderate to conservative Democrat, Stevenson emerged from the rural Hill Country to become Speaker of the Texas House, Lieutenant Governor, and finally governor.

Stevenson was neither a staunch New Deal liberal nor a states rights zealot of the later Dixiecrat variety. Instead, he occupied a middle ground between these two extremes. He supported the expansion of certain government programs and infrastructure spending, while advocating for strict fiscal discipline in the state budget.

A former bookkeeper and bank president, Stevenson began his administration with a state treasury deficit and ended with a surplus. His political career was marked by institutional and party loyalty. Generally, he backed the Roosevelt Administration throughout the war, despite occasional disagreements over federal policies.

Early Life and Legal Career

Coke Robert Stevenson was born on March 20, 1888, near Mason, Texas, the son of a former Confederate soldier and a deeply religious mother. He received minimal formal education and was largely self-taught. In his youth, Stevenson worked as a teamster, freight hauler, and bank janitor, gradually rising to become a bank president by his early 30s. Without attending law school, he studied independently and passed the bar exam in 1913. That same year, he was elected county attorney of Kimble County, launching a public career that would span more than three decades.

Stevenson later served as county judge and district attorney before winning a seat in the Texas House of Representatives in 1928. During the tumultuous years of the Great Depression, he gained a reputation as a quiet, businesslike legislator with a deep knowledge of procedure and a belief in fiscal conservatism. However, he supported spending increases to expand the state highway system, increase teacher salaries, and improve the state universities.

By 1933, Stevenson was Speaker of the House, and in 1938, he was elected Lieutenant Governor under W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, an unconventional populist with whom Stevenson shared few political instincts but maintained a working relationship.

Governorship During World War II

Stevenson became governor on August 4, 1941, when O’Daniel resigned after winning a seat in the U.S. Senate. Less than four months later, the United States entered World War II. Stevenson’s tenure as governor thus coincided almost exactly with the launch of the American war effort. While Texas was distant from the battlefront, the state became a critical site for military training, industrial expansion, and agricultural production.

Stevenson’s wartime leadership style was marked by restraint and administrative competence. He expanded state cooperation with federal agencies to accommodate the surge in military bases, airfields, and defense plants across Texas. Cities like San Antonio, Fort Worth, and Houston saw rapid wartime growth, while rural areas experienced labor shortages and migration to war-related industries.

At the state level, Stevenson supported wartime rationing, civil defense, and military service programs, but he resisted federal involvement in certain policy areas and maintained strong control over state finances. A staunch opponent of deficit spending, he refused to raise taxes and insisted on paying down state debt, even during wartime mobilization. His approach reflected Depression-era skepticism of centralized authority and an older tradition of Texas fiscal caution.

Despite the scale of wartime transformation, Stevenson avoided major political confrontation. He did not pursue headline-grabbing reforms or seek to reshape state government. Instead, he prioritized continuity, law and order, and efficient administration. His low-key style, in sharp contrast to the populist theatrics of his predecessor, earned him broad respect across party lines.

He was elected in his own right in 1942 and reelected in 1944 without serious opposition—an unusual feat in the faction-ridden politics of Texas Democrats. During these years, the state government saw modest investment in infrastructure and education, but Stevenson remained wary of expanding public programs.

Views on Race and Segregation

Coke Stevenson governed Texas during the Jim Crow era, when segregation in schools, public facilities, and elections was state policy. Several historians have described Stevenson as a racist, pointing to certain comments and policy views, and noting his close ties to the segregationist wing of the Texas Democratic Party.

For example, while serving in the Texas House in 1929, he said, “Certainly I disapprove of social equality between the White and Negro races. I disapprove of any recognition of a negro which has a tendency to promote social equality.”1 Stevenson reaffirmed these views in an interview nearly 40 years later.2

However, at the height of Ku Klux Klan power in the 1920s, Stevenson opposed the group. He once noted that he had voted against the Klan candidate in the 1924 Democratic gubernatorial primary, preferring T.W. Davidson, a foe of the Klan, and in the primary runoff he voted for Miriam Ferguson, another outspoken opponent of the Klan. He said,

“When the run-off came about, it was between Mrs. Miriam A. Ferguson and Felix Robertson of Dallas. Robertson was widely known throughout this country as a member of the Ku Klux Klan, or at least they said he was being supported by the Klan. The people of Kimble County had never been identified with the Klan in any way. So I went with Mrs. Ferguson in that run-off.”3

During Stevenson’s years in office, issues of race were not at the forefront of political debate, as they were in the 1950s and 1960s, and the governor seldom addressed racial matters directly. His most direct involvement in race issues came in connection with U.S.-Mexico relations and the treatment of Mexicans in Texas. In 1943, at the urging of President Franklin Roosevelt, Stevenson visited Mexico and created a “Good Neighbor Commission,” which was charged with investigating discrimination and mistreatment of migrant laborers. It ended up carrying out anti-discrimination work until the 1970s.

“I think it did a great deal of good,” Stevenson later reflected. “I heard of instances all the way from Brownsville to El Paso—up and down the Rio Grande—where [the commission] effected reconciliations and turned misunderstandings between the citizens of Mexico and our people into good arrangements.”4

“I received fine reports from the Good Neighbor Commission—so much so that, as you know, the Legislature subsequently authorized it as an agency of the state government and gave it official status, which up to that time it had held only by executive order from the governor’s office. A good many able men have served on that commission since. I think it’s been really worthwhile in promoting good relations with our neighbors across the Rio Grande.”

The Good Neighbor Commission was connected with a broader wartime effort by the Roosevelt Administration to maintain diplomatic goodwill with Latin American countries, amid fears that the Axis powers could exploit anti-American sentiment in this region.

Stevenson recalled the circumstances of its creation:

“As you know, when we got into the war, there was some alarm that maybe Mexico might give us some trouble. [President Roosevelt] called me and asked me to go down to Mexico City and, as he expressed it, ‘keep them from sticking a knife in our back.’ So I went and stayed a week. Nelson Rockefeller came down and spent some time with me and General George Marshall. We got along nicely with the Mexican authorities—never had any more trouble with them. In order to carry out a policy that had been expressed orally to the Mexican authorities, I created, without any legislative authority, the Good Neighbor Commission in Texas.”5

Overall, this episode reflected wartime pressures more than a commitment to civil rights. It stands as a rare example of civil rights success in Texas before the 1950s.

Postwar Challenges and Transition

By the end of the war in 1945, Texas faced a new set of challenges: inflation, returning veterans, housing shortages, and labor unrest. Stevenson approached these postwar issues with the same cautious, fiscally conservative mindset that had defined his wartime governance.

He supported the continued segregation of public facilities and opposed federal efforts to intervene in state racial policies. Stevenson also resisted calls for expansive social programs or labor protections, believing such matters should remain local and limited in scope. He navigated growing tensions within the Democratic Party between conservatives and liberal New Dealers. Stevenson firmly identified with the former group.

Having served more than five years as governor, Stevenson declined to run for another term in 1946 and retired from state office. At the time of his departure, he was the longest-serving governor in Texas history—a record that reflected not flamboyant leadership, but consistent administrative stewardship during a demanding time.

In 1948, Coke Stevenson ran for the U.S. Senate in a hotly contested Democratic primary against Congressman Lyndon B. Johnson. Initially the frontrunner, Stevenson led the first round of voting and appeared to have narrowly won the runoff, but late returns—particularly from Jim Wells County’s infamous Box 13—shifted the outcome in Johnson’s favor by just 87 votes. Stevenson alleged widespread fraud and sought legal intervention, but the Democratic State Central Committee certified Johnson’s victory amid national scrutiny. Though Stevenson appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, his challenge failed, and Johnson secured the nomination—effectively winning the seat in one-party Texas. The episode became one of the most controversial elections in Texas history and marked a turning point in Johnson’s rise to national power.

After the 1948 Senate race, Stevenson withdrew from public life, disillusioned by what he viewed as the corruption of modern politics. He returned to his ranch in Junction, Texas, and resumed his work in banking and cattle ranching, remaining active in local civic affairs but refusing to reenter the political arena.

Though he received occasional encouragement to seek office again, he declined, insisting that the political climate no longer reflected the principles of honesty and restraint he had long championed. In later years, he was often visited by journalists, historians, and political observers seeking his perspective on Texas politics, but he remained largely private. He died on June 28, 1975, at the age of 87.

Sources Cited

- Journal of the House of Representatives of the Second and Third Called Sessions of the Forty-First Legislature of the State of Texas, pg. 211 (Austin: Von Boeckmann-Jones Co., 1929). ↩︎

- Governor Coke R. Stevenson, interview by North Texas State University Oral History Collection, no. 293, May 13, 1979, pg. 33. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 7. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg 89. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg 88. ↩︎