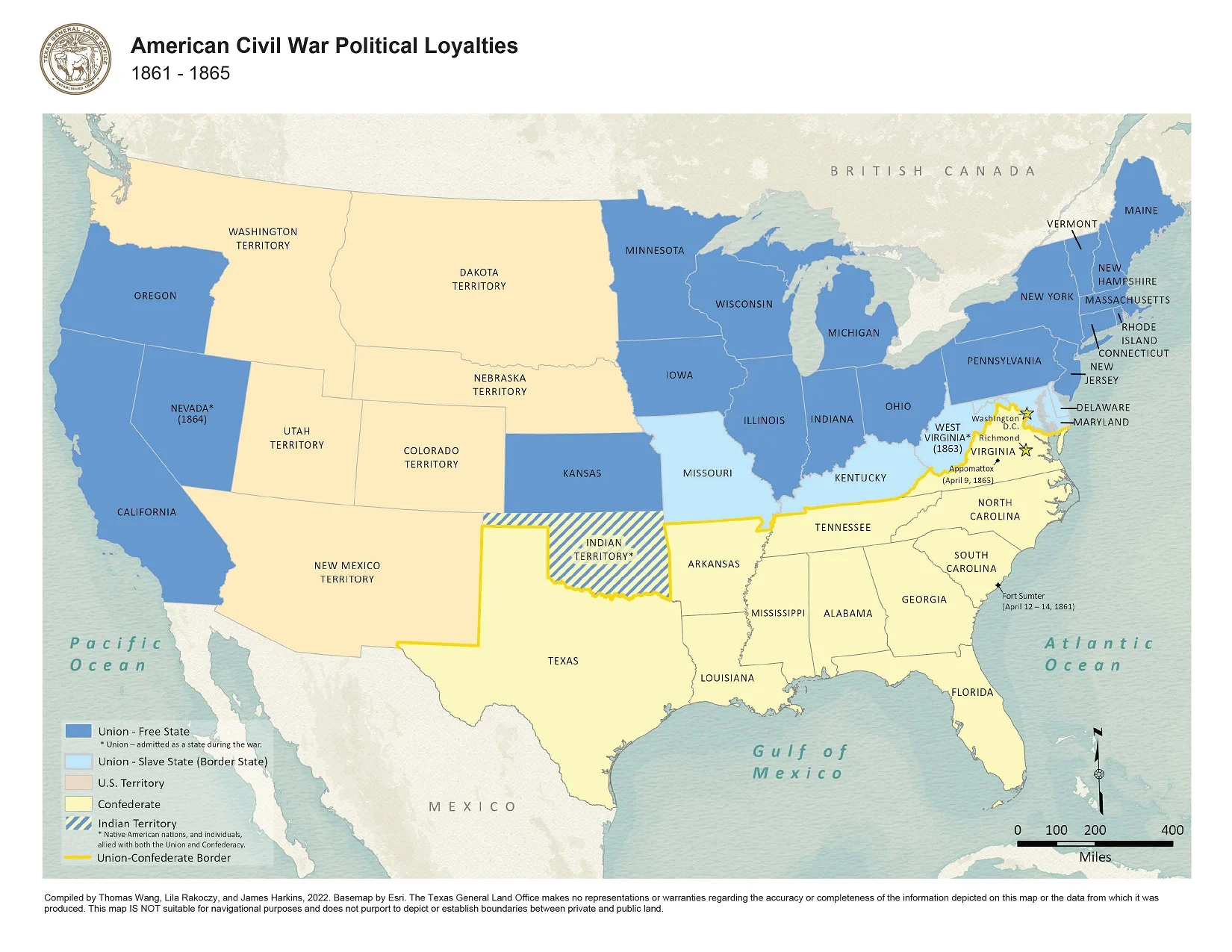

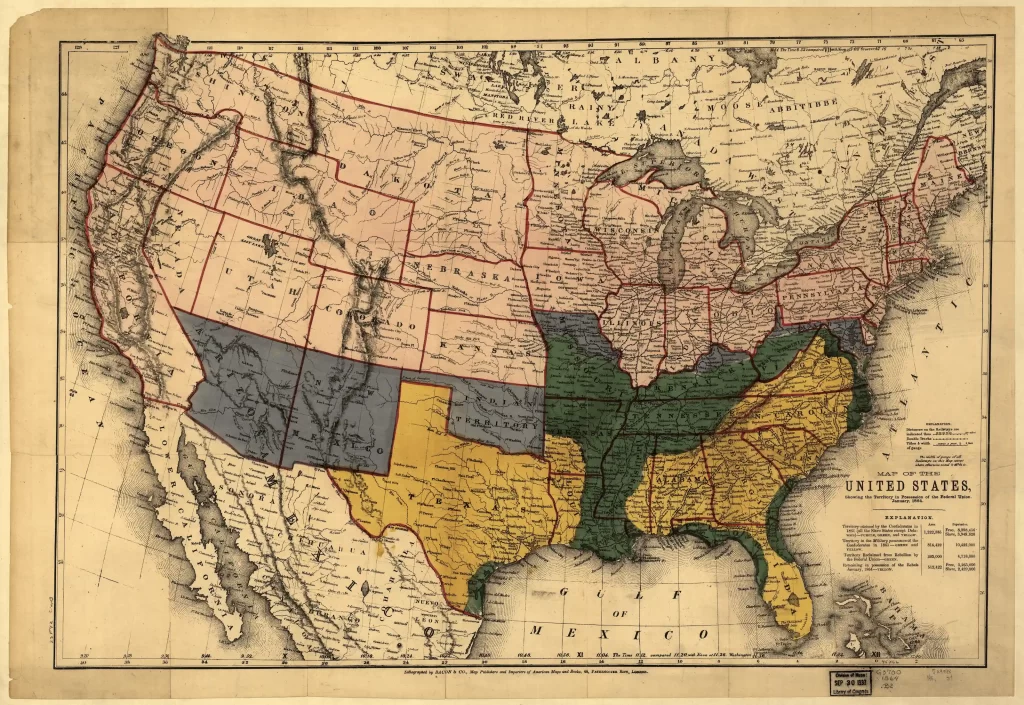

Texas stood at the political and geographic periphery of the American Civil War (1861-1865), and though it witnessed only a handful of military engagements on its own soil, its role in the conflict was far from marginal. As one of the largest Confederate states, Texas served as a critical supplier of men, horses, and resources to distant battlefronts. Tens of thousands of Texans fought in major campaigns in Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi—far more than ever saw combat within Texas itself.

What action the state did see was largely coastal or borderland in nature: a series of naval clashes, defensive battles, and cross-border skirmishes that underscored its vulnerability and value. Texas’s Civil War experience was shaped not by large-scale invasion, but by its role as a Confederate stronghold on the western frontier, its vital access to Mexican trade routes, and the divided loyalties of its civilian population.

Secession and Strategic Significance

Texas formally seceded from the Union on February 1, 1861, following a vote by the Secession Convention in Austin. The decision was later ratified by popular referendum. A new state constitution was adopted and Governor Sam Houston was removed from office after refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy. Despite Houston’s resistance, the state joined the Confederate States of America and began mobilizing its population and resources for war.

Strategically, Texas offered several advantages: its sheer size, relative insulation from early Union advances, abundant cattle and cotton, and a long border with Mexico. That international border—unlike the rest of the Confederacy’s perimeter—offered a potential lifeline for trade and diplomatic maneuvering as Union blockades tightened elsewhere.

Texas and the Broader Confederate War Effort

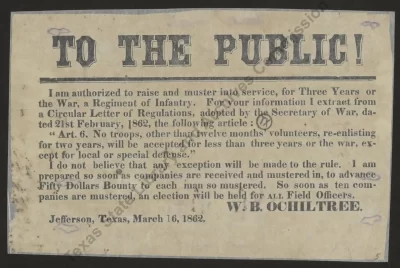

Although Texas was not a primary theater of Civil War combat, it was a primary source of manpower for the Confederate war machine. By the war’s end, more than 70,000 Texans had served in Confederate forces, with thousands more involved in militia units, frontier defense, or supply roles. These soldiers were disproportionately sent eastward, where the major battles of the war unfolded.

Perhaps the most famous of these units was Hood’s Texas Brigade, an elite infantry unit that fought under Generals Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet in the Eastern Theater. The brigade participated in many of the war’s most consequential battles, including Antietam, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga, earning a reputation for discipline, aggression, and high casualty rates. Lee himself is said to have remarked, “The Texans always move them.”

Other units, such as Terry’s Texas Rangers (the 8th Texas Cavalry), fought with distinction in the Western Theater, participating in campaigns from Kentucky to Georgia. Texas cavalry units were especially prized for their riding skill and effectiveness in mobile warfare.

While many Southern states were ravaged by Union occupation, much of Texas remained under Confederate control throughout the war. This geographic insulation allowed Texas to serve as a training ground and supply depot, even as the Confederate heartland crumbled. It also made the state a source of steady reinforcements, even late in the conflict.

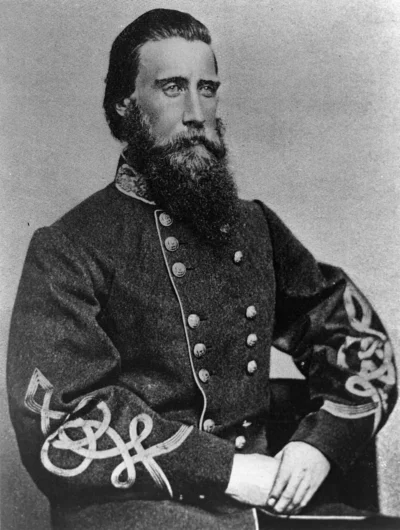

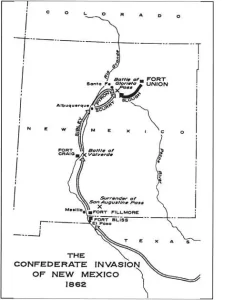

The New Mexico Campaign

Texas saw relatively few major land battles, but the engagements that did occur were often tactically creative or symbolically potent. In one of the Confederacy’s most ambitious western offensives, a force of about 2,500 Texas troops under General Henry Sibley invaded New Mexico Territory in early 1862. The goal was to seize Union forts and secure a Confederate corridor to the Pacific.

Sibley’s force, known as the Army of New Mexico, captured several key settlements, including Albuquerque and Santa Fe. The campaign culminated in the Battle of Glorieta Pass in March 1862. Though Confederate forces initially pushed back Union troops, their supply train was destroyed in a daring flanking maneuver. This logistical loss forced Sibley to retreat across the desert, ending Confederate ambitions in the Southwest.

Though fought outside Texas, the campaign was led by and largely manned by Texans. For many of the Texans involved, the long retreat from New Mexico through arid land marked one of the most grueling episodes of the war.

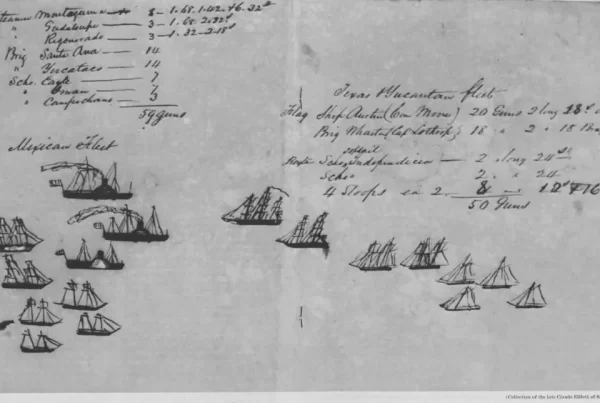

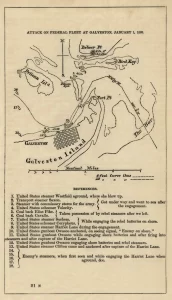

The Battle of Galveston

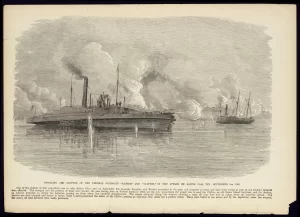

After Union forces captured the strategic port city of Galveston in the fall of 1862, Confederate General John B. Magruder launched a daring counterattack on New Year’s Day 1863. The operation involved a two-pronged assault: Confederate infantry advanced across a narrow railroad causeway from the mainland, while Confederate naval forces attacked Union warships in the harbor using “cottonclads”—steamboats armored with tightly packed bales of cotton.

.

Though outgunned, the Confederate vessels managed to ram and board Union ships in close combat, while the land forces pushed back the occupying troops on the island.

The combined assault succeeded in forcing the Union garrison to surrender or retreat, and Galveston was retaken. The victory offered a significant morale boost to the Confederacy and reopened a limited channel for trade and blockade-running. Galveston remained in Confederate hands for the rest of the Civil War, making it one of the few major ports in the South to do so.

The Battle of Sabine Pass

One of the war’s most improbable Confederate victories unfolded in September 1863, when a Union flotilla attempted to force its way through the Sabine River. The operation aimed to seize Sabine Pass as a gateway for a deeper advance into eastern Texas, ultimately capturing Beaumont and disrupting Confederate control along the Gulf Coast.

Fewer than 50 Confederate defenders under Lieutenant Richard Dowling stood in their way. Many of Dowling’s men were Irish immigrants who had settled in the Gulf Coast region in the 1840s and 1850s; their knowledge of the waterways, combined with rigorous artillery drills, allowed them to fire with deadly precision from Fort Griffin. In a short but decisive engagement, their gunners sank two Union gunboats and captured more than 300 prisoners.

The defeat abruptly ended the Union’s planned advance, securing the Texas–Louisiana border for the remainder of the war and preserving a vital Confederate supply corridor. Sabine Pass became a celebrated victory and an enduring symbol of outnumbered defense in the Trans-Mississippi theater.

The Red River Campaign

After the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863, Union armies gained momentum, threatening wider parts of the South, even as heavy fighting continued in Virginia. At the start of 1864, Union commanders developed a plan for a major offensive aimed at penetrating deep into Confederate-held Louisiana and eastern Texas. Commanded by Union General Nathaniel P. Banks and supported by Admiral David Porter’s naval forces, the operation’s immediate objective was Shreveport, the Confederate headquarters in the Trans-Mississippi.

The campaign was part of a broader strategy to disrupt Confederate logistics, destroy plantations, and deter the French — who had intervened in Mexico — from aiding the South.

Thousands of Texans fought on both sides of the campaign, including Confederate troops under General Richard Taylor who mounted a fierce defense against the Union advance. Both Confederate military authorities and the civil government of Texas, led by Governor Pendleton Murrah, viewed the offensive as a serious threat and responded accordingly, forcibly recruiting and thereby worsening an already serious manpower shortage in Texas itself. Historian B.P. Gallaway, a professor at Abilene Christian University, explains:

“When [General Nathanial] Banks launched the Red River campaign in Louisiana… all available troops, not essential for holding the enemy at bay in [coastal] Texas, were ordered to Arkansas and Louisiana. Texas African Americans were pressed into military service to build barricades and repair railroads and highways, but they were not trusted with firearms… Governor Murrah transferred all troops detailed to noncombatant jobs to combat duty and initiated an impressment program which forced old men, beardless boys, bushwhackers, deserters, and all types of shirkers into military service.”1

The campaign’s major clashes—including the battles of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill—took place in Louisiana but involved numerous Texas regiments. These engagements resulted in heavy casualties and logistical setbacks for the Union. At Mansfield in particular, Taylor’s outnumbered forces inflicted a sharp defeat on Banks, derailing the Union timetable and forcing a chaotic retreat down the Red River.

Though the campaign never crossed into Texas, its impact in the state was significant. Thereafter, Confederate authorities feared an incursion into the state’s northeast, and troops continued to be needed to secure Shreveport and other gateways to the state. Union troops stationed on the Texas coast faced less resistance and moved more freely, launching patrols deep into eastern Texas in the final year of the war.

Additionally, the forced recruitment of Texans to fight in the Red River Campaign worsened mounting problems of internal dissent and resentment toward Confederate authorities. For communities in East Texas, the Red River Campaign brought shortages of able-bodied men, livestock, and laborers. Small farms were left to widows, children, and the elderly.

Although the Red River Campaign ultimately failed to achieve its objectives, it exposed vulnerabilities in Texas’s defenses and weakened the already fragile Confederate government.

The Battle of Palmito Ranch

The final land battle of the Civil War was fought on Texas soil—ironically, after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Union troops under Colonel Theodore Barrett attempted to occupy Brownsville but were driven back by Confederate forces under Colonel John S. Ford. Though strategically pointless, the Confederate victory at Palmito Ranch is often cited as the war’s last battle.

Other Engagements and Skirmishes

Lesser-known confrontations included the Battle of Laredo (March 1864), in which Confederate Colonel Santos Benavides repelled Union forces attempting to burn cotton stores near the border, and numerous raids in Central and West Texas. Although these engagements were small, they demonstrated the persistence of conflict even in remote regions.

Naval Warfare and Blockades on the Texas Coast

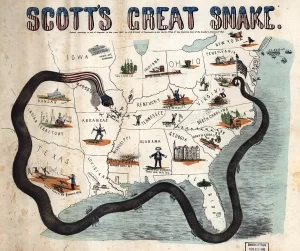

While land battles were rare, Texas played a more consistent role in naval warfare. The Union Navy sought to enforce its “Anaconda Plan” by blockading Southern ports, and Texas’s coastline—stretching over 350 miles—was a prime target.

In response, Confederate agents and merchants turned to blockade running. Merchant ships sometimes were able to slip past the Union patrols. Additionally, bales of cotton and other goods were smuggled out of Texas and across the Rio Grande to Matamoros. From there, cotton could be exported legally by neutral European vessels, bypassing the blockade. Ships then returned carrying weapons, medicine, and luxury goods.

Confederates also adapted naval technology. Cottonclads—steamers reinforced with cotton bales—played crucial roles in the recapture of Galveston and other engagements. These improvised vessels reflected the state’s material constraints and innovative responses.

Ultimately, however, the dominance of the U.S. Navy played a major role in the defeat of the Confederacy. Lacking both a navy to protect its ports and manufacturing capacity, the Confederacy could not adequately equip and supply its troops in the field.

The Navy also facilitated amphibious operations that allowed the Union to seize parts of the Texas coast. Control was only temporary at times. For example, Indianola was occupied twice before being abandoned. Yet joint Navy-Army operations on the coast helped the Union to tighten the blockade and drew Confederate troops and resources away from the main theaters of battle.

Borderlands and the Mexican Connection

Perhaps the most geopolitically significant feature of Civil War-era Texas was its international border with Mexico. The 1,200-mile Rio Grande frontier offered the Confederacy a rare opening to world markets, especially after the Union blockade tightened.

The Mexican port of Bagdad, located just across the border from Brownsville, became a lifeline for Confederate commerce. Cotton was transported by wagon across South Texas, ferried into Mexico, and then exported to European buyers. In return, Confederate agents acquired arms, clothing, and other vital supplies.

Though officially neutral, Mexican President Benito Juárez tolerated this activity—partly for revenue, and partly to balance U.S. pressure during Mexico’s own internal conflict. The Union government viewed the trade as an obstacle to its blockade but avoided direct military conflict with Mexico.

In November 1863, Union General Nathaniel P. Banks launched an expedition to seize Brownsville, hoping to shut down the Confederate cotton route. Union troops occupied the city for several months but failed to hold it permanently. When they withdrew in 1864, Confederate forces quickly reoccupied the area. The episode highlighted the fragile and shifting control in border zones.

Civilian Experience and Divided Loyalties

Although spared the destruction suffered by much of the South, Texas civilians still endured hardship and political violence. The Confederate draft, economic dislocation, and shortages caused unrest. By 1863, imported goods like coffee, sugar, and shoes had become scarce luxuries. Families adapted by using parched corn or roasted acorns as coffee substitutes, weaving homespun clothing, and bartering for necessities. Confederate currency, plagued by inflation, was often refused in favor of gold, silver, or barter arrangements.

In German-settled areas such as the Hill Country, many residents remained loyal to the Union or adopted a stance of neutrality. This internal dissent led to harsh reprisals. The most infamous occurred in Gainesville in 1862, when Confederate officials hanged over 40 men suspected of Unionist sympathies—a mass execution now known as the Great Hanging.

In other regions, early enthusiasm for the Confederate cause gave way to disillusionment, desertion, and occasional acts of resistance. Forced recruitment deepened divides between ardent secessionists and reluctant participants in the Confederate cause.

Women took on greater responsibilities in managing farms, businesses, and households during the absence of men. Enslaved African Americans in Texas remained in bondage throughout the war—emancipation came belatedly, in June 1865 (Juneteenth), after the arrival of Union troops in Galveston.

Legacy and Commemoration

Although Texas did not witness the epic scale of Civil War combat, its battles, military contributions, and border politics remain important chapters in the war’s history. Sites such as Galveston, Sabine Pass, and Palmito Ranch are now preserved as historic landmarks, commemorated through plaques, interpretive markers, and periodic reenactments.

For generations, public memory in Texas emphasized Confederate valor and regional pride, often framed through the lens of the “Lost Cause”—a tradition that cast the Southern war effort in heroic terms while downplaying the central role of slavery and sidestepping the realities of defeat. This perspective shaped educational materials, public monuments, and civic rituals across much of the 20th century.

In recent decades, however, commemorative narratives have shifted. Historians and the broader public have increasingly turned their attention to the war’s lasting social consequences: the unfinished promise of emancipation, the fierce legal and political struggles of the Reconstruction period, and the systems of racial segregation that followed.

As a result, new historical interpretations have emphasized not only military service and battlefield strategy, but also dissent, civilian hardship, and the long arc of inequality that extended well into the 20th century.

- B.P. Galloway, Texas: The Dark Corner of the Confederacy (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), pg. 14. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Hood’s Texas Brigade: The Soldiers and Families of the Confederacy’s Most Celebrated Unit

- Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness

- A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy

- Decisions of the Red River Campaign: The 15 Critical Decisions That Defined the Operation

- Texas Coastal Defense in the Civil War

- Civil War Scoundrels and the Texas Cotton Trade

- The Texas Lowcountry: Slavery and Freedom on the Gulf Coast, 1822–1895

- Vicksburg: Grant’s Campaign That Broke the Confederacy

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.