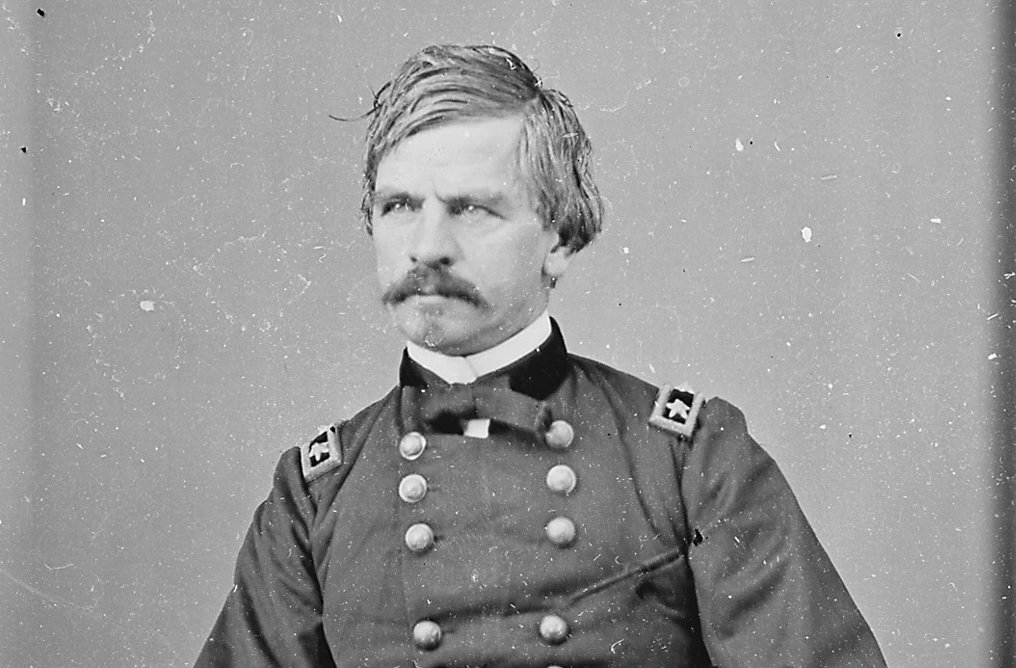

Soon after he became commanding general of the U.S. Army in 1864, Ulysses Grant ordered Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks, commander of the Department of the Gulf, to “abandon Texas entirely, with the exception of your hold upon the Rio Grande.”1

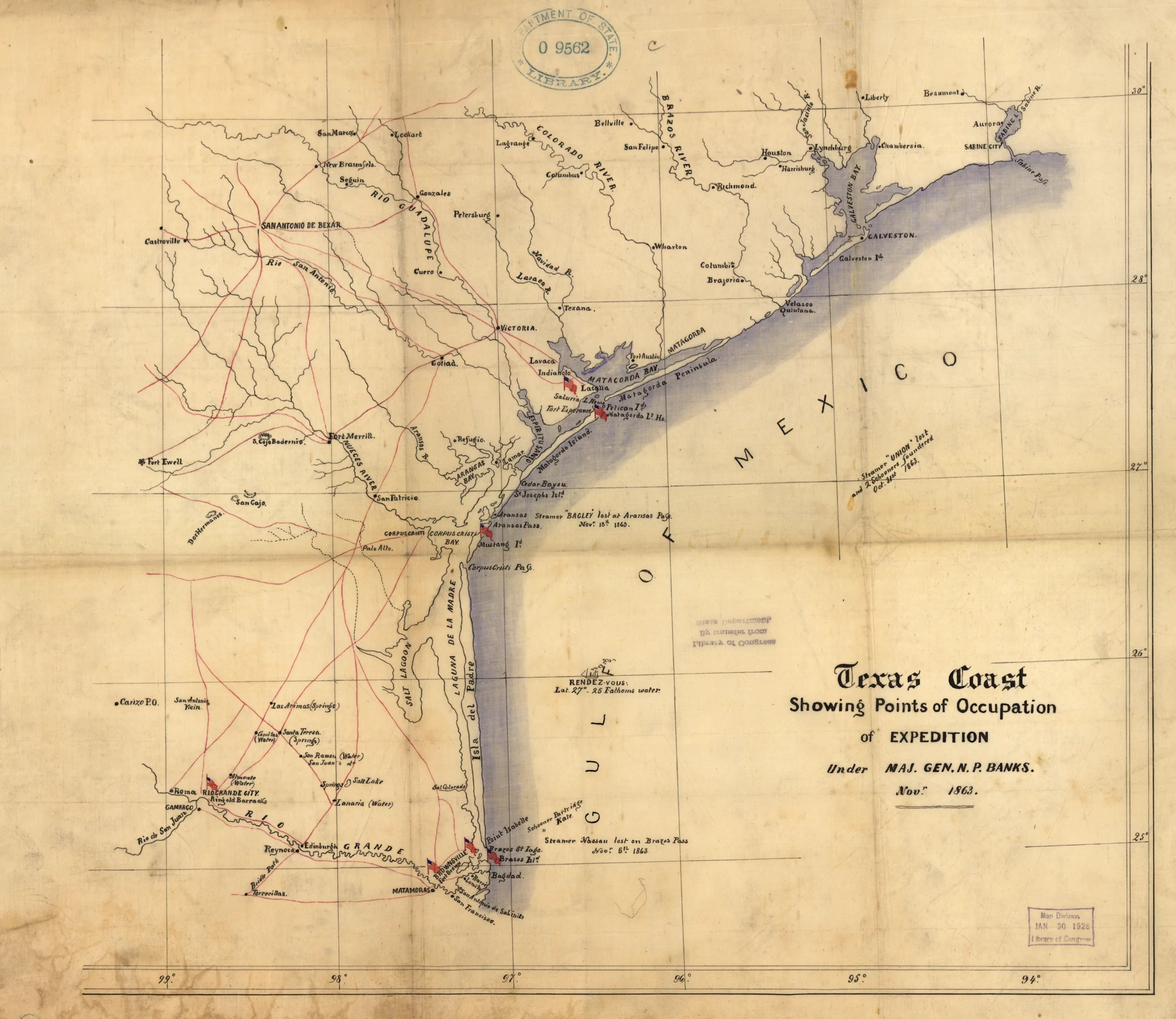

The order reflected Grant’s disapproval of the Texas campaign, which is seen here at its height in November 1863. Grant wanted to concentrate Union troops and direct them against the strongest Confederate cities and armies, which he aimed to find and destroy.

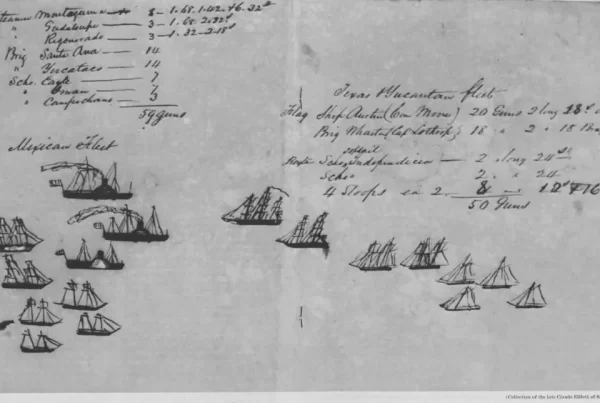

By contrast, Banks’ campaign had been based on a different strategic concept: strangling the Confederate economy through a naval blockade and the capture of key coastal strongholds and ports. Additionally, the campaign had a political objective, namely, White House concerns about a potential French intervention in Texas on behalf of the Confederates.

In the fall of 1863, President Abraham Lincoln and his Chief of Staff Henry Halleck asked Banks to draw up operations against the Texas coast. They feared that the French might send weapons and supplies to the Confederates in Texas, or send troops to Texas in connection with their ongoing campaign in Mexico — which would ultimately make it impossible for the United States to restore its authority in Texas without a confrontation with France.

(The French expedition was ostensibly about forcing Mexico to repay debts, but also represented an intervention on behalf of Mexican conservatives against the liberals of Benito Juárez. Further, it reflected the imperialist ambitions of Napoleon III, who yearned for military glory like his uncle Napoleon Bonaparte. The invasion installed Archduke Maximilian of Austria as Emperor of Mexico, until the withdrawal of French troops and the capture and execution of Maximilian in 1867).

As seen on this map, Banks’ campaign succeeded in capturing strongpoints controlling Matagorda Bay, Corpus Christi Bay, and the mouth of the Rio Grande. It was a combined Army-Navy operation launched from New Orleans, involving approximately 10,000 men.

But Banks failed to fully control the coast and lost a key battle at Sabine Pass. Despite the ongoing war, Many Texan planters succeeded in exporting their cotton through Mexican ports or through the use of “blockade runners” — swift ships that specialized in evading Union naval patrols.

Even so, the Union operations along the Texas coast seriously disrupted the Confederate Texas economy, worsened inflation, and gave the U.S. Army bases from which they planned to carry out raids deep into the Texas interior. Furthermore, Banks’ campaign worsened political tensions within Texas amid growing popular unrest over conscription and Confederate Army demands for troops in the east. At the time, Texan politicians faced competing demands to send more troops out of the state, or keep them at home to provide coastal defense and protect the frontier.

This map was produced by the War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General. Dated November 1863, it is titled “Texas Coast Showing Points of Occupation of Expedition Under Major General N.P. Banks.” The physical copy of this item is held by the National Archives in Washington, D.C. (National Archives Identifier 305823). Though this was a military map, it was also shared with the general public in the North as a means of boosting morale and showing progress of the war effort. It was published in The New York Herald on March 28, 1863.

Grant’s decision to abandon this campaign meant that Texas was eventually the last Confederate state to be occupied by Union troops at the end of the war in 1865.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, appendix, “Report of Lieutenant-General U. S. Grant, of the United States Armies, 1864–65,” July 22, 1865, Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5865/5865-h/5865-h.htm ↩︎