Arrest and booking are the first formal steps in a Texas criminal case. Governed by statutes and constitutional principles, these procedures determine how an individual enters the system and what legal safeguards apply from the moment of custody.

What Constitutes an Arrest?

An arrest in Texas occurs when a law enforcement officer takes a person into custody under the authority of law, typically based on probable cause that a criminal offense has been committed. Arrests may occur with a warrant issued by a magistrate or, under certain conditions, without a warrant—such as when the offense is committed in the officer’s presence or when there is a risk that evidence will be destroyed.1

At the moment of arrest, the individual is entitled to know the reason for their detention. Officers must advise the individual of their Miranda rights before conducting a custodial interrogation, including the right to remain silent and the right to legal counsel. These protections stem from the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as well as Article I, Section 10 of the Texas Constitution, which protects against self-incrimination.

What Happens During Booking?

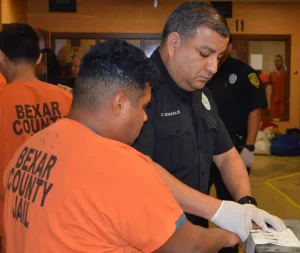

Following arrest, the individual is transported to a county jail, municipal holding facility, or detention center for booking. This is the process by which the person is formally entered into the criminal justice system. Although the procedures vary slightly by jurisdiction, certain core steps are nearly universal.

First, law enforcement officers collect identifying information, such as the arrestee’s name, date of birth, and address. The arresting agency records the alleged offense(s) and documents the circumstances of the arrest. Fingerprinting and photographing—commonly referred to as taking a “mugshot”—are standard practice and serve to link the arrestee to official criminal records.2

The individual is searched for weapons and contraband, and any personal belongings are confiscated, inventoried, and held by the facility until release. Authorities also check for outstanding warrants, which may impact the person’s detention status. Some counties perform a basic health and mental health screening at this stage, including suicide risk assessments, consistent with standards for jail operations under Texas law.3

The accused remains in custody until release or judicial review, typically in a holding cell or general population area of the jail. Importantly, under Article I, Section 11 of the Texas Constitution, individuals are generally entitled to bail unless charged with certain capital or violent offenses. Although the specific procedures for setting bail vary, the constitutional presumption favors pretrial liberty.

This article is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The laws and procedures discussed herein reflect Texas statutes and legal norms as of the time of writing and may be subject to change. Individuals facing arrest or criminal charges should consult a licensed attorney for guidance specific to their situation. Texapedia is a privately maintained encyclopedia and does not provide legal representation or services.

Initial Appearance Before a Magistrate

Texas law requires that any person arrested without a warrant be brought before a magistrate “without unnecessary delay,” and in all cases within 48 hours of arrest.4 This initial appearance, often referred to as a magistrate warning or Article 15.17 hearing, serves several critical functions.

The magistrate must verify the identity of the arrestee, inform them of the charges, and explain their constitutional rights, including the right to counsel, the right to remain silent, and the right to an examining trial in felony cases. If the individual cannot afford an attorney, the court must begin the process of appointing one.5

The magistrate also sets bail or determines conditions of release, subject to constitutional and statutory limits. For some misdemeanors or low-level offenses, release on personal bond may be considered. In felony or higher-risk cases, the court may require surety bonds or impose conditions such as GPS monitoring or protective orders.

Reform and Legislative Developments

In recent years, Texas has seen increased scrutiny of the arrest and pretrial detention process, particularly concerning fairness, equity, and public safety. Many arrestees—especially those charged with low-level, nonviolent offenses—may spend days in jail not because they pose a flight risk, but because they cannot afford to post bail. This dynamic has led to calls for reform and litigation over the constitutionality of cash-based detention systems.

The Texas Legislature continues to consider changes to improve the efficiency and fairness of the arrest-to-booking pipeline, including proposals to expand cite-and-release authority, improve data transparency, and standardize procedures for early release. Reform efforts also aim to better identify individuals who pose a genuine risk to public safety—ensuring that dangerous arrestees can be lawfully held without bail, while others are not jailed simply due to inability to pay.

Due Process Rights

Throughout the arrest and booking process, individuals retain core protections under the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These include the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, the right against self-incrimination, the right to counsel, and the right to due process of law. The Texas Constitution mirrors many of these safeguards in Article I, particularly Sections 9 through 13.

Any deviation from these protections—such as prolonged detention without a magistrate hearing, coercive questioning without counsel, or failure to notify the accused of their rights—may result in dismissal of charges, suppression of evidence, or civil liability.

Next Steps After Booking

After booking and a magistrate hearing, the individual may be released—on bond, personal recognizance, or other terms—or remain in jail awaiting further proceedings, depending on the charges and the court’s assessment of risk and flight potential.

While many constitutional protections are actively exercised during the arrest and booking stages, others—such as the presumption of innocence—remain in effect but are not yet visible in practice. Under both the U.S. Constitution (5th and 14th Amendments) and Texas Constitution (Article I, § 19), every person accused of a crime is presumed innocent unless and until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. This presumption shapes how prosecutors must present evidence and how juries are instructed, but it does not prevent temporary detention or the filing of charges.

Similarly, while individuals have the right to confront witnesses and compel evidence in their favor, those rights are primarily exercised later in the process—during trial or formal hearings. Arrest and booking are merely the entry point into the legal system; at this stage, the accused does not have the opportunity to contest the evidence or assert a defense—they are required to comply with lawful commands. Yet even then, the presumption of innocence and the right to due process remain firmly in place, shaping all that follows.