Background

After winning independence in 1836, the Republic of Texas remained in a state of uneasy tension with Mexico. The Mexican government refused to recognize Texas’s sovereignty and repeatedly threatened to reclaim its former province. By late 1841, Antonio López de Santa Anna had returned to power in Mexico and adopted a strategy of sending armed incursions to harass the Texas frontier.

Santa Anna‘s objective was not reconquest — a goal considered too far out of reach, given the financial cost and military risk of mounting a full-scale invasion. Rather, he intended to deter foreign investment and immigration to Texas, while demonstrating that Mexico still claimed the rebellious province.

In March 1842, General Rafael Vásquez led a force that briefly occupied San Antonio (raising the Mexican flag there) before withdrawing back across the Rio Grande. This raid caused panic among Texans and underscored the young republic’s vulnerability. Although President Sam Houston declared an emergency during the crisis, he was cautious about launching any counter-invasion. Vásquez’s withdrawal ended the immediate threat, but the episode set the stage for a larger Mexican invasion later that year.

The Capture of San Antonio

Determined to strike a more decisive blow, Santa Anna dispatched General Adrián Woll to Texas in the late summer of 1842. Woll led approximately 1,400 Mexican troops – including infantry, cavalry, and artillery – with orders to seize San Antonio de Béxar and hold it. Advancing by an unexpected route to avoid Texan scouts, Woll’s column crossed the Rio Grande and approached San Antonio from the west. At dawn on September 11, 1842, the Mexican force achieved complete surprise. They surrounded San Antonio and swiftly stormed into the town, overpowering the small Texan garrison after a brief skirmish. Within hours, San Antonio was under Mexican control. Woll’s men took dozens of Texans prisoner, including a district judge and two congressmen who were in town for court business.

The fall of San Antonio – for the second time that year – sent shockwaves through Texas. Woll’s invasion also inflamed distrust between Anglo-Texans and Tejanos; notably, former Texas revolutionary Juan N. Seguín rode with Woll’s forces, heading a militia company, an act viewed by Anglo settlers as proof of Tejano disloyalty. Seguín later claimed that Mexican authorities had forced him to take up arms, by threatening to imprison him for his role in the Texas Revolution.

Woll fortified the town and awaited reinforcements that ultimately never arrived. His presence deep in Texas spurred an urgent Texan military response.

Battle of Salado Creek

Within days, Texan volunteers gathered to confront Woll. About 200 militia and Rangers, under captains Mathew “Old Paint” Caldwell and John C. “Jack” Hays, assembled east of San Antonio. Rather than attack the Mexican positions head-on, the Texans planned to lure Woll’s army into the open. On September 18, Hays led a small mounted party to feign an attack near San Antonio and then retreated toward a prepared Texan position along Salado Creek. The ruse worked: Woll dispatched a large portion of his forces out of the town in pursuit of what he thought was a fleeing enemy. Several miles from San Antonio, the Mexican troops rode straight into an ambush.

Caldwell’s men, concealed along the creek bed and behind trees, poured deadly fire into the exposed Mexican columns. The Battle of Salado Creek raged for several hours as the Mexicans made repeated attempts to overrun the Texan line. However, the Texans’ superior marksmanship and advantageous defensive terrain repelled every charge. Mexican casualties mounted (scores of soldiers killed or wounded) while Texan losses were very light. By late afternoon, General Woll realized his situation was untenable. He broke off the attack and pulled his battered troops back toward San Antonio. The Texans had won a decisive victory, stalling the Mexican invasion.

Dawson Massacre

On that same day, a separate confrontation proved disastrous for a group of Texan reinforcements. Captain Nicholas Dawson had raised a company of 53 volunteers from Fayette County and marched to aid in the fight. As Dawson’s men approached the area on September 18, they were intercepted by a much larger force of irregular Mexican cavalry detached from Woll’s main body.

The Texans hastily took up a defensive position in a small grove on the prairie. A brief but brutal fight ensued. Vastly outnumbered and under cannon fire, Dawson’s company was overwhelmed. About 36 Texans, including Dawson, were killed, and 15 survivors were taken prisoner after surrendering. Only a couple of men escaped. This incident, remembered as the Dawson Massacre, shocked the Texas community and intensified calls for retribution against the Mexicans.

Retreat and Aftermath

With his offensive blunted, General Woll decided to retreat. On September 20 – little more than a week after his arrival – Woll evacuated San Antonio and began a withdrawal towards the Rio Grande, taking along the captured Texans (approximately 60 prisoners in total). A number of San Antonio’s Tejano families who had assisted the Mexicans or feared reprisals also left with the departing army.

Texan forces pursued the retreating invaders for several days. A skirmish at the Hondo River occurred when Texas Rangers caught up to Woll’s rear guard, but the Mexicans managed to fend off the pursuers and continue south. Hampered by muddy terrain and the swift Mexican retreat, the Texans eventually abandoned the chase. By the end of September, Woll’s expedition had recrossed the Rio Grande into Mexico, effectively ending Mexico’s last incursion into the Republic of Texas.

The dramatic events of September 1842 had significant political fallout. The ease with which Mexican troops had taken San Antonio (twice in one year) and the losses at the ‘Dawson Massacre’ inflamed public outrage in Texas. President Houston’s administration, pressured to respond, authorized a counteroffensive later that winter. In November 1842, a Texan volunteer force under General Alexander Somervell marched to the Rio Grande intending to punish Mexico, but it accomplished little and eventually turned back. Some dissident volunteers continued into Mexico without official sanction, launching the ill-fated Mier Expedition in December.

The Mier force was defeated and captured, leading to further loss of Texan lives and a new group of prisoners sent to Mexican jails. Ultimately, most of the Texans captured during the Woll invasion and the subsequent expeditions were held in Perote Prison until 1843–44, when diplomatic efforts and changes in the Mexican government secured their release.

Political Fallout in Texas

Though short-lived, the Woll invasion achieved Santa Anna’s objective of weakening the Republic of Texas financially. It affected the currency and worsened government indebtedness. The invasion also intensified internal political tensions. At the time, two major factions dominated Texas politics: a conciliatory faction led by Sam Houston, which sought peace with Mexico and annexation by the United States; and an expansionist faction led by Mirabeau Lamar, who pursued a military policy.

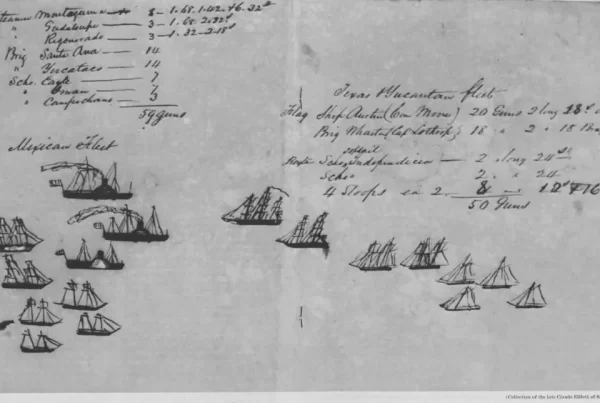

Politically, the invasion had mixed results. In the short term, it inflamed public sentiment against Mexico and stirred Texan nationalism. This weakened Houston politically and strengthened the war party. The Mier Expedition and the Yucatán Campaign — a naval campaign that Houston tried and failed to prevent — demonstrated the limits of Houston’s control, and the military ambitions of the Texan people.

However, in the longer term, the Woll invasion bolstered the case for annexation — the opposite of what Santa Anna intended. Many prominent Texans were businessmen and planters who stood to profit from peace and political stability. Though willing to fight to repel Mexican incursions, they did not necessarily favor imperial adventures and counter-raids. The surest way to prevent Mexican re-annexation — and to solve the problems of the currency and government indebtedness — was to join the United States.

The events of 1842 also contributed to long-term racial tensions within Texas. Tejanos, who had been part of the Texas Revolution, found themselves distrusted and politically excluded during the remaining years of the Republic and in the early Statehood period.