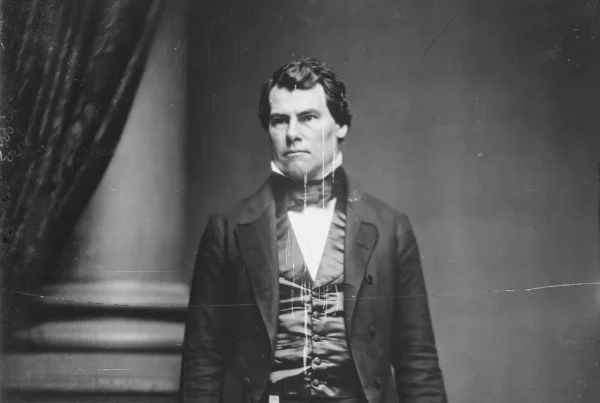

William Pettus Hobby served as the 27th governor of Texas from 1917 to 1921, steering the state through the final years of World War I, the ratification of Prohibition, and the suffrage movement that redefined women’s participation in politics. His administration reflected the reformist impulses of the Progressive Era while remaining grounded in the conservative political traditions of the state’s one-party government at the time.

Early Life and Career

Hobby was born on March 26, 1878, in Moscow, Polk County, Texas, to Edwin E. Hobby and Dora Pettus Hobby. His father was a lawyer, state senator and appellate judge, who wrote A Treatise on Texas Land Law (1883). The family’s relative prominence provided Hobby with access to educational and professional opportunities. He attended high school in Houston, where the family moved when he was a teenager, but did not pursue a formal college degree. Instead, he gravitated toward the world of newspapers, which at the time offered both professional advancement and a platform in public life.

By his twenties, Hobby was working as a journalist in Houston. He joined the staff of the Houston Post in 1895 and rose steadily through its ranks. In 1907, he became president of the paper, a role that brought him lasting influence in civic and political affairs. He later left the post and became manager and owner of the Beaumont Enterprise.

Entry into Politics

Hobby’s growing stature in Houston led to political opportunities within the dominant Democratic Party. Hobby’s path to power was similar to that of O.B. Colquitt a few years earlier. Both were newspapermen and Democrats, though their politics differed substantially; Hobby occupied a place within the urban Progressive wing of the party, while Colquitt was more closely tied with rural interests and the saloon lobby.

In 1914, Hobby was nominated for lieutenant governor of Texas on a ticket headed by James E. Ferguson, despite never having held political office. Ferguson, a populist outsider, won the governorship, while Hobby secured the lieutenant governorship.

As lieutenant governor, Hobby presided over the Texas Senate, managing legislative duties with an even-handedness that earned him respect. His opportunity for higher office came unexpectedly in 1917 when Ferguson was impeached and removed from office for misapplication of public funds and conflicts with the University of Texas.

Hobby, as lieutenant governor, constitutionally succeeded Ferguson. Taking office at age 39, he was (and remains) the youngest person to serve as Governor of Texas.

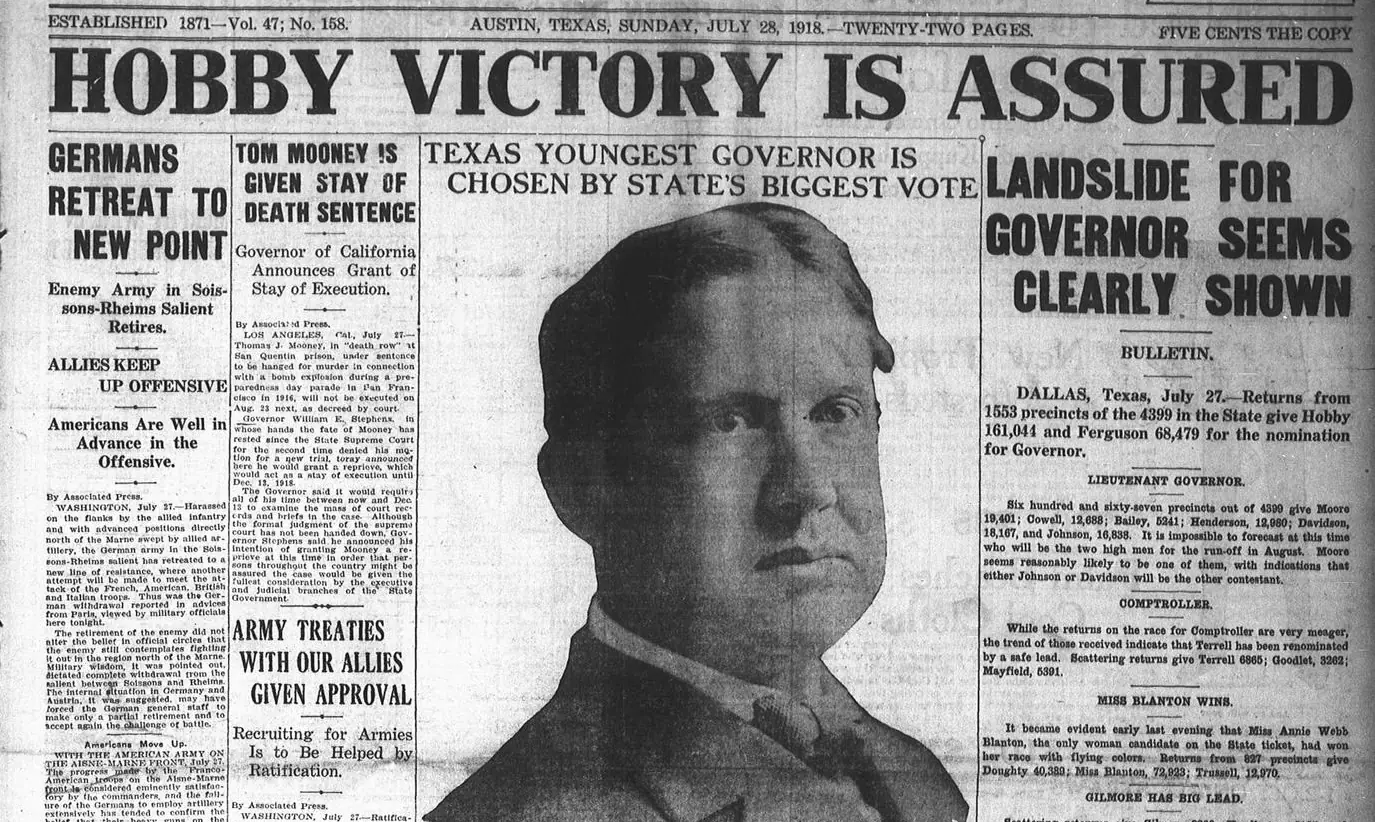

Election of 1918

After serving out the remainder of Ferguson’s term of office, Hobby was elected to a full term of his own in 1918, defeating Ferguson, who attempted a political comeback. His victory was decisive and reflected the electorate’s desire for stability during a period of war and domestic reform. Ferguson campaigned aggressively against the impeachment verdict, casting himself as a champion of the common man, but many voters still associated him with corruption and scandal.

Hobby, by contrast, drew support from business leaders, reformers, and women’s suffrage advocates, who saw him as a steady hand at a critical moment. The campaign became a referendum not only on Ferguson’s record but also on the broader Progressive-era reforms that were reshaping Texas politics.

World War I Context

Texas was deeply affected by World War I. The state served as a training ground for tens of thousands of soldiers at newly established military installations such as Camp Logan and Camp Bowie. Hobby’s administration coordinated with federal authorities to ensure the mobilization of resources, infrastructure, and labor for the war effort. He also oversaw programs to boost agricultural production and promote war bond campaigns, emphasizing civic duty and loyalty at a time of heightened national sentiment.

In his inaugural address, delivered January 17, 1919, Hobby celebrated the Allied victory in Europe, striking a patriotic and optimistic tone that deflected attention from the state’s recent political turmoil and characterized the future as brighter than the past. His remarks were at times florid and even comical; he boasted:

“Before [our] mighty and glorious army crossed four thousand miles of a turbulent sea to carry freedom to the Old World, the Emperor of Germany proudly and vainly boasted that he would eat his ham and eggs in the city of Paris; but after the Sammy boys [U.S. troops]… we soon found the Emperor of Germany boiling his sauerkraut from a dilapidated old castle in Holland.”1

Progressive Reforms

Hobby’s tenure coincided with the broader Progressive Era, which emphasized efficiency in government, regulation of industry, and social reform. He endorsed a state minimum wage, new laws to protect tenants, and measures to improve state administration, including reforms to the prison system and enhancements in public health programs. Tuberculosis prevention campaigns and maternal health initiatives gained momentum under his leadership, reflecting growing public health awareness in Texas.

Prohibition and Suffrage

Two of the defining issues of Hobby’s governorship were Prohibition and women’s suffrage. The movement for Prohibition had gained traction in Texas well before national ratification. Hobby, reflecting widespread support among the state’s voters, endorsed the Eighteenth Amendment, and state legislation soon mirrored the national ban on alcohol.

More consequential in shaping Texas politics was women’s suffrage. In 1918, Hobby signed a bill granting women the right to vote in primary elections, a measure that extended suffrage to a large segment of the population in practice, since Democratic primaries were the dominant electoral contests in the state. This development anticipated the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 and demonstrated the growing political influence of Texas women’s organizations. The partial suffrage reform is often remembered as one of Hobby’s key contributions.

Education and Economy

Economically, Texas in the late 1910s was shifting from a predominantly agrarian economy toward one increasingly influenced by oil discoveries and urban growth. The Spindletop oil field, discovered in 1901, had already begun to transform the state’s industrial profile. Hobby supported investment in infrastructure to facilitate growth, including road construction, which was becoming increasingly important with the rise of the automobile.

Public education remained a pressing issue, as the state grappled with rural-urban disparities and limited funding. Hobby supported modest increases in funding for public schools, though significant structural improvements would not emerge until later administrations. His efforts nonetheless reflected Progressive Era priorities of extending education as a means of civic uplift.

Marriage and Family

Hobby’s personal life was closely tied to his public career. In 1915 he married Willie Chapman Cooper, the daughter of a congressman. Their union connected him more firmly to the city’s business and social elite at a time when his political fortunes were ascending.

Willie Hobbie renovated the Governor’s Mansion and was politically and socially active. She won praise in the Texas press, with the Austin American-Statesman calling her a “brilliant, learned, well-poised and well minded woman,” and the Houston Press writing that she “made the Mansion at Austin a mecca for thousands. She reined there with a democracy that thrilled the most humble and brought equal praise from the most aristocratic.”

Willie Hobby died in 1929 after a long illness, leaving the ex-governor widowed during his fifties. In 1931, he married Oveta Culp, a rising figure in Houston journalism and public service who was 26 years his junior. Oveta Culp Hobby would later achieve national prominence as director of the Women’s Army Corps during World War II and as the first U.S. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Their marriage became one of the most visible partnerships in Texas public life, blending his established political reputation with her emerging career on the national stage.

The couple had two children, William Pettus Hobby Jr. and Jessica Hobby Catto. Their son, often known as Bill Hobby, pursued a political career of his own and served as lieutenant governor of Texas from 1973 to 1991, making him the state’s longest-serving holder of that office. The Hobby family thus remained a political dynasty in Texas across much of the twentieth century.

Later Life

Hobby chose not to seek another term in 1920, stepping away from active political office. He returned to his newspaper interests, resuming leadership of the Houston Post. His business acumen and political connections helped him maintain influence in Houston and Texas public life. He also engaged in banking and other civic enterprises, further consolidating his reputation as both a businessman and statesman.

Through the 1920s and beyond, Hobby remained active in Democratic Party affairs, though he never again sought elective office. His wife, Oveta Culp Hobby, carried the family name into national prominence, and together they became one of the most notable political couples in Texas. As he aged, Hobby progressively turned over control of his newspaper business to his son, William P. Hobby Jr., who would become lieutenant governor.

William Pettus Hobby died on June 7, 1964, in Houston at the age of eighty-six. He was survived by his wife, Oveta Culp Hobby, and their two children, William and Jessica Hobby Catto.

- Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated after the end of the war in November 1918 and went into exile in the Netherlands, where the Dutch government granted him political asylum. He settled initially at Amerongen Castle, to which Governor Hobby is referring. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with this recommended title: