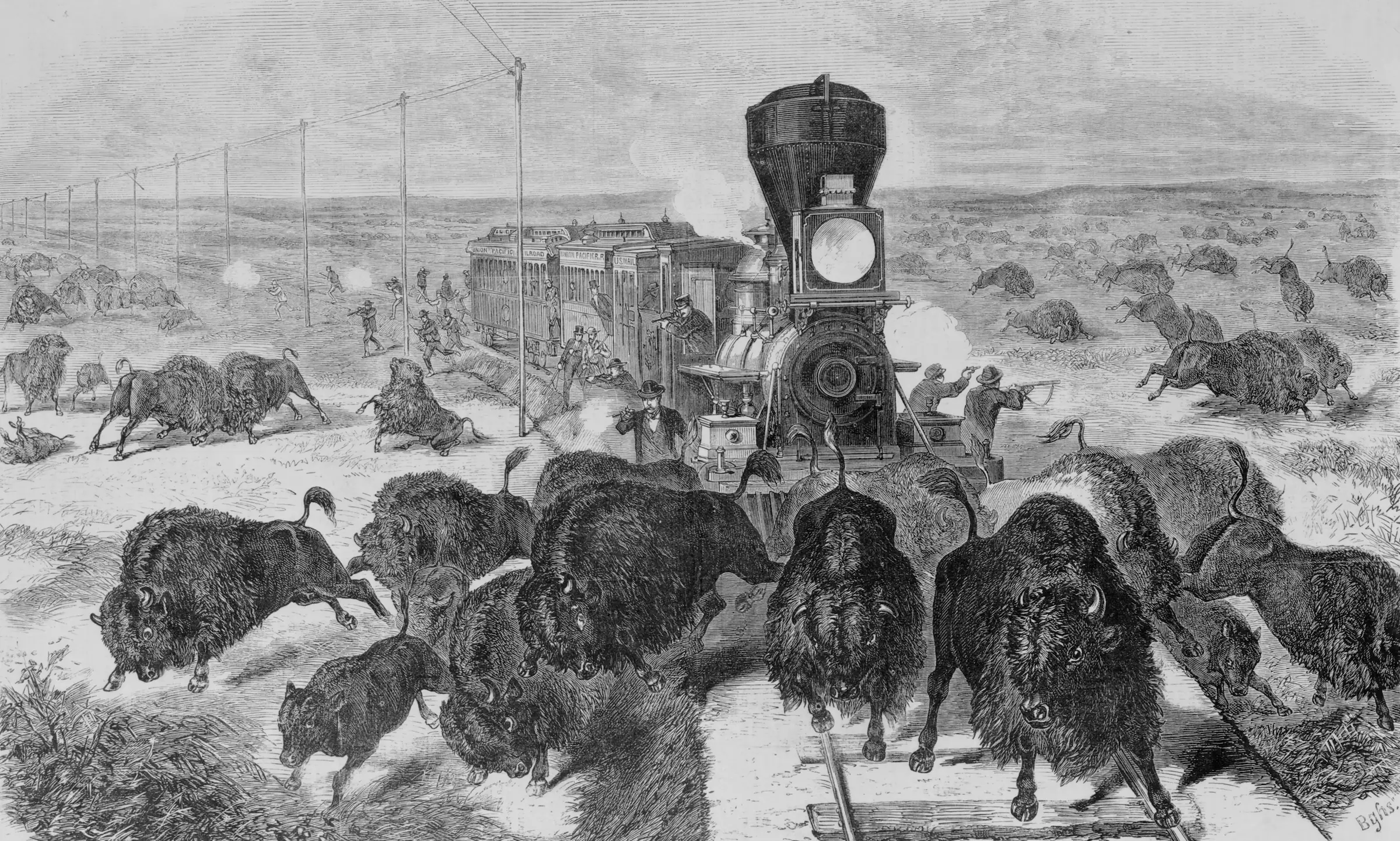

Hunters killed millions of bison across the Great Plains during the 1870s, bringing the species to the brink of extinction. In Texas, the killing intensified as railroads expanded and markets for hides and bones grew. The U.S. government promoted westward settlement, and some military leaders openly supported the killing as a way to force Indian tribes to abandon their traditional way of life. Ranchers, traders, and settlers saw the bison as both a resource to exploit and a barrier to development.

Commercial hunters, backed by rail access and a growing market for hides, bones, and meat, found a lucrative trade in the slaughter. But the scale and rapidity of the killing would not have been possible without tacit and explicit support from federal officials. Some policymakers saw extermination as a tool of conquest. General Philip Sheridan famously endorsed the hunters’ work, declaring that the destruction of the bison would do more to “settle the vexed Indian question” than the army could. By removing the primary food source of Plains tribes, officials hoped to force Indigenous communities onto reservations and into dependency.

Railroads and Hunters

At the center of the 1870s bison extermination was a new industrial landscape. The extension of the Texas & Pacific and other railroads into the western plains enabled rapid transport of hides to eastern markets. Buffalo hunters—many of them former soldiers or immigrants—set up temporary camps and moved in organized waves across the Llano Estacado and High Plains, using breech-loading rifles to kill hundreds of animals a day.

The bison were well adapted to fending off natural predators — mostly wolves — but they did not adapt well to the arrival of modern ranged weapons. Herding together, standing ground, and using sheer mass and numbers had always served them well against wolves, yet these very instincts left them exposed to hunters armed with powerful rifles. Gunfire from a distance did not trigger the same flight response as a wolf pack, and as animals fell, the rest often milled in confusion rather than scattering.

“The man I sold my .44 to killed 119 buffalo in one day with it,” recalled Kansas hunter R.W. Snyder. “That beats me with my Big .50, as 93 is the most that I ever killed in one day.” Such tallies illustrate how a survival strategy that had worked for millennia failed against modern technology.

The prime killing season was in the winter, when the hides were thickest and of the highest value, meaning that hunters struck the herds at their most vulnerable time of year. Bison also had relatively poor eyesight compared to other prey animals, relied more heavily on smell and hearing, and lacked natural cover on the open plains. Their bulk and slower running speed further limited escape once panic set in, sealing their fate.

Hunting became industrialized. Crews worked with assembly-line efficiency: shooters dropped bison from a distance while skinners harvested hides, leaving the carcasses to rot. Hunting teams usually consisted of four men or more, including one shooter, skinners, and sometimes a camp manager and teamster. Bones were later collected and sold for fertilizer and manufacturing. The hide trade alone generated millions of dollars annually, and the scale of the operation quickly overwhelmed any local or moral objections.

Texas lawmakers did nothing to intervene. Proposals to protect the bison were considered, and rejected. Unlike some northern Plains states, which began to discuss restrictions as early as the 1870s, Texas had no laws protecting bison, nor any wildlife policy infrastructure. In fact, the absence of regulation was a selling point in encouraging further settlement and economic exploitation.

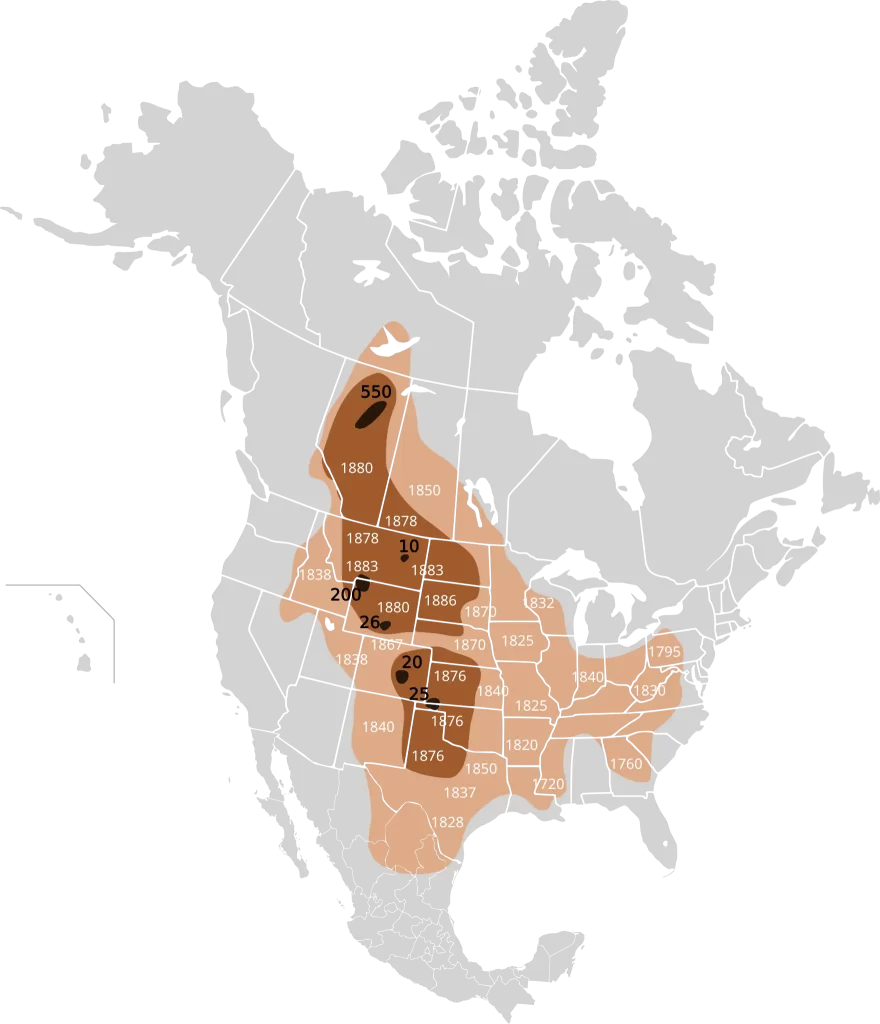

By the end of the decade, the Southern Herd—once the largest bison population on the continent—was functionally extinct. The Texas Plains, which had echoed for centuries with the thunder of migrating bison, fell silent.

Impact on the Plains Indians

The most immediate and devastating consequence of the bison extermination was borne by Indigenous peoples, including the Comanche and Kiowa of Texas. The collapse of the herds destroyed the economic and cultural foundations of their way of life, forcing a final reckoning with the reservation system imposed by the U.S. government.

The Red River War of 1874–75, which took place in the Texas Panhandle, was in many ways a direct response to the bison crisis. The fighting began when Comanche and allied Kiowa warriors attacked a camp of bison hunters at Adobe Wells. This triggered a U.S. Army offensive that ended a long era of Comanche dominance on the Llano Estacado. In the war’s aftermath, the U.S. Army rounded up the remaining bands and confined them to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

The Indians’ defeat in the Red River War opened up new regions to the hunters. Vast regions of north and west Texas where they had once feared to roam now became prime hunting grounds. In a book about the Texas frontier, historians Robert F. Pace and Donald S. Fraser explained,

“After the defeat of the Comanches and Kiowas, the destruction of the southern herd would be systematic and efficient. A building crescendo of hunting outfits jostled and scrambled to established the best base for the hunt, and clever businessmen were happy to assist. Hunters [moved out of] Dodge City [and Fort Elliot] within weeks of Quanah Parker’s surrender in the early summer of 1875… hunters prowled the grasslands, killing an astonishing number of animals and stripping them of their hides before heading back to base. Buyers also came, bidding on the best specimens before bundling them into bales and consigning them to shippers hauling on to Dodge City.”1

Native elders later remembered the 1870s not just as an era of military defeat but as a spiritual catastrophe—a loss of identity and place. Oral histories from Kiowa and Comanche descendants continue to speak of the bison slaughter in terms of trauma and betrayal.

The transformation of the Texas Plains was swift. With bison gone, cattle ranching expanded rapidly. Grasslands once sustained by seasonal migrations were fenced, grazed, and gradually degraded. The region’s ecological balance shifted—from the intricate rhythms of nomadic hunting cultures to the demands of global commodity markets. Farming on the plains would later lead to the Dust Bowl ecological disaster of the 1930s.

Collapse and Near Extinction

The killing of the bison peaked in the winter of 1876-1877 with tens of thousands of bison slaughtered, or more. But the decline thereafter was precipitous.

“The 1877-1878 season started well, but by March 1878 yields were a third of what they had been. The age of the buffalo hunter was passing. By October of that year, journalists in the Fort Griffin Echo crowed that the next boom had arrived, and that ‘trail traffic’ [supplying and guiding settlers] was replacing the buffalo trade. Merchants and hunters alike, spoiled by the days of easy money, turned to other lines of work.”2

By 1883, the organized hide trade in Texas had effectively ceased. There were no more bison to kill. Observers reported entire regions where not a single animal remained. Commercial hunters, having exhausted the resource, moved north to finish off the remaining central and northern herds. Nationally, it is estimated that the population of bison dropped from 30 million in 1800 to fewer than 1,000 by the 1890s.

Incredibly, no laws were passed to protect the species during the period of most intense destruction. The only surviving bison in Texas by the mid-1880s were a few scattered animals kept in private hands or hiding in remote canyons and inaccessible grasslands. One of the most important surviving groups came from a small herd captured and preserved by famed Texas rancher Charles Goodnight, who, along with his wife Mary, maintained bison on their J.A. Ranch near the Palo Duro Canyon. This group, numbering fewer than a dozen animals at one point, would become critical to later preservation efforts.

The end of the great herds stirred a shift in public opinion. While earlier decades had treated the bison as an inexhaustible commodity or obstacle to development, the 1880s saw the emergence of regret, scientific curiosity, and the first hints of advocacy. Naturalists like William Temple Hornaday began documenting the bison’s decline in alarming terms. His 1889 report, The Extermination of the American Bison, shocked readers and helped galvanize elite support for limited recovery.

Still, it was too late to preserve the original wild herds of Texas. The extermination had been total, and its effects would last for generations. The survival of the species into the 20th century came not from state leadership or federal legislation, but from isolated acts of stewardship by private citizens and a small cadre of emerging conservationists.

Conservation Response

In the early 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt cited the bison’s near-extinction as a rallying cry for preservation. Captive breeding efforts and protected reserves such as Yellowstone National Park allowed small herds to survive, though never again at the scale of the pre-slaughter era.

In Texas, a few bison were eventually reintroduced in parks and ranches, including the Caprock Canyons State Park herd descended from animals preserved by rancher Charles Goodnight. Eventually, Texas built a regulatory framework for environmental protection through agencies like the Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission (established in 1907) and its successor, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Bison once roamed nearly all of Texas, from the High Plains and central prairies to parts of South Texas, avoiding only the dense eastern forests and coastal marshlands. Today, they can only be seen Caprock Canyons, San Angelo State Park, and at various private ranches and preserves, where they are maintained for conservation, tourism, or breeding programs.

Nationally, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, there are approximately 20,000 bison living in the wild and an additional 420,000 in commercial herds. Bison are no longer considered endangered, and their meat is marketed as a leaner alternative to beef.

Sources Cited

- Robert F. Pace and Donald S. Fraser, Frontier Texas: History of a Borderland to 1880 (Abilene: State House Press, 2012), 172-173. ↩︎

- Pace and Fraser, Frontier Texas, 182-183. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History

- Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo

- The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750–1920

- Return of the Bison: A Story of Survival, Restoration, and a Wilder World

- Comanches: The History of a People

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.