The impeachment of Governor James E. Ferguson in 1917 marked a dramatic fall from power for one of Texas’s most polarizing political figures. A two-term Democrat known for his populist appeal among rural voters, Ferguson was removed from office by the Texas Senate after being convicted on multiple charges, including misapplication of public funds and attempts to coerce the University of Texas.

Nicknamed “Pa,” or “Governor Jim,” Ferguson later staged a political comeback when his wife Miriam (or “Ma” Ferguson) was elected and served two terms as governor, during which he exercised considerable influence.

The episode remains the only successful impeachment of a Texas governor and stands as a significant case study in the constitutional limits of executive authority and the role of legislative oversight (Texas Constitution art. XV, § 1).

Background and Political Rise

James E. Ferguson emerged as a prominent figure in Texas politics during the Progressive Era, though his appeal was more populist than reformist. Born in 1871 near Salado, Texas, Ferguson worked as a lawyer and banker before entering politics. He gained notoriety as an advocate for tenant farmers and small landowners, positioning himself as a champion of rural Texans against the economic and political dominance of urban elites and large corporations.

Elected governor in 1914 and reelected in 1916, Ferguson promised fiscal restraint, increased aid to rural schools, and resistance to centralized power. His administration coincided with growing tensions between conservative institutions and the expanding role of government amid World War I mobilization and changing social dynamics. Though popular with his base, Ferguson often clashed with other centers of influence—including the press, state agencies, and the University of Texas.

Conflict with the University of Texas

The seeds of Ferguson’s impeachment were sown in his escalating dispute with the University of Texas. In 1916, Ferguson sought to have several faculty members removed, allegedly for political disloyalty and personal opposition to his administration. When the university’s regents, supported by President Robert Vinson, refused to dismiss the targeted professors, Ferguson retaliated by vetoing the entire appropriation for the university in the 1917 budget.

This move provoked immediate backlash, not only from academic and business leaders but also from within the legislature. Critics accused Ferguson of abusing the line-item veto for personal and political reasons, undermining the state’s educational institutions. Ferguson defended his actions by arguing that public universities should be subject to executive oversight and reflect the values of taxpayers and elected officials.

While this conflict alone did not constitute grounds for impeachment, it galvanized opposition and brought broader scrutiny to Ferguson’s conduct in office. Legislators began to question his management of public funds and his relationship with state agencies, particularly regarding financial irregularities tied to the Governor’s Mansion account and state banking regulations.

More broadly, Ferguson faced growing opposition to his governorship from Prohibitionists and Suffragists—both causes that he opposed. The triumph of both of these causes in 1919 illustrates that Ferguson was swimming against the political tide, so to speak.

Impeachment Charges and Trial

On July 21, 1917, the Texas House of Representatives voted to impeach Governor Ferguson, citing 21 separate charges. These ranged from misapplication of public funds to coercion of university officials and improper use of gubernatorial influence in the banking sector. The central legal basis for impeachment lay in Article XV of the Texas Constitution, which permits removal of executive officials for “willful neglect of duty, incompetency, habitual drunkenness, oppression in office, or other reasonable cause” (Texas Constitution art. XV, § 1).

After his impeachment, Ferguson was suspended from office pending the outcome of the Senate trial. The Senate convened as a court of impeachment in August 1917, with the Lieutenant Governor presiding. Of the 21 charges, the Senate sustained 10, including allegations that Ferguson had misused state funds and deposited public money in banks where he held personal interest—violating the principles of public trust and financial propriety.

Ferguson did not attend the Senate trial, arguing that the proceedings were unconstitutional and that the legislature lacked authority to question his policy decisions.

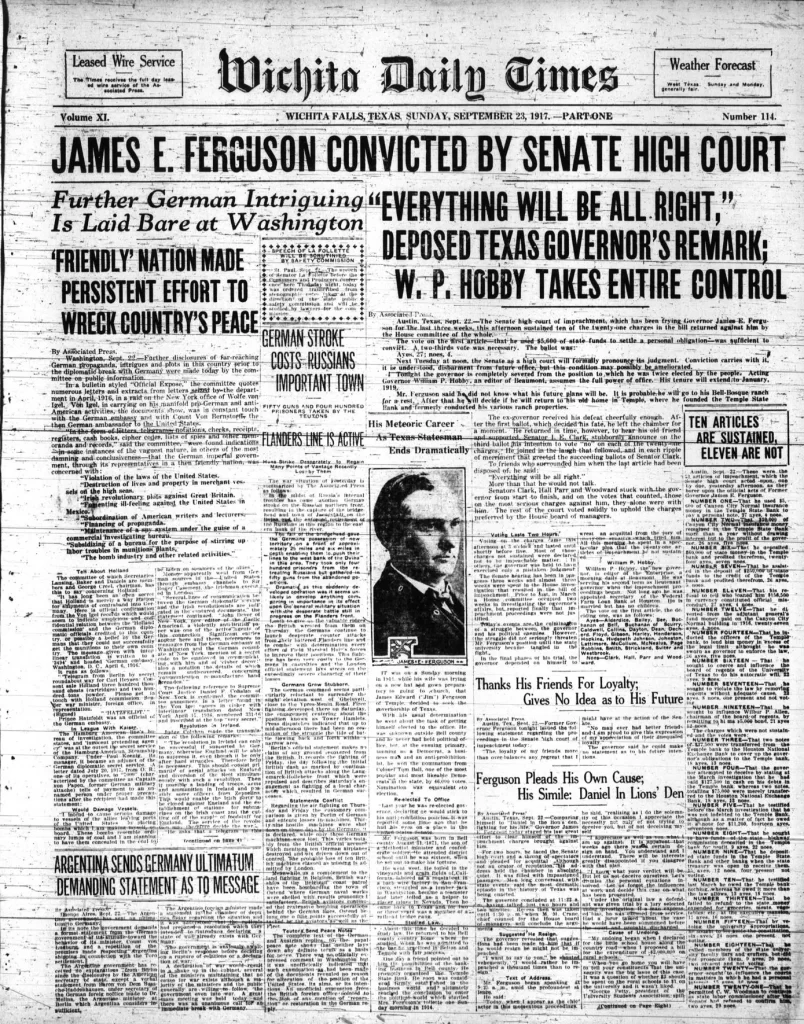

When it became clear that he would be convicted in the Senate, Ferguson resigned from office in an attempt to preempt the formal judgment and avoid the constitutional penalty of disqualification. He maintained that his resignation rendered the proceedings moot and that the Senate no longer had jurisdiction to bar him from future office. Nevertheless, the Senate proceeded with its vote, convicting him on ten counts on September 22, 1917, removing him from office, and declaring him ineligible to hold public office in Texas.

Ferguson challenged the outcome in court, but the judgment of the Court of Impeachment was upheld, establishing that resignation did not nullify the legislature’s authority to complete the impeachment process and impose sanctions.

Contemporary observers were divided on the impeachment’s legitimacy. Supporters of Ferguson claimed the charges were politically motivated, rooted in elite resistance to his anti-establishment agenda and rural appeal. Critics countered that the evidence of financial misconduct was clear and that Ferguson’s attack on the University of Texas demonstrated a disregard for the principles of limited government and institutional independence.

Aftermath and Legacy

Following Ferguson’s removal, Lieutenant Governor William P. Hobby succeeded him and was later elected in his own right. The impeachment and its resolution helped reassert the legislature’s constitutional authority to check executive power and underscored the accountability mechanisms embedded in Texas government. It also marked one of the few times in U.S. history when a sitting state governor was formally removed from office.

Despite his disqualification, Ferguson remained a potent political force. In 1924, his wife, Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, ran for governor with James serving as her chief advisor and campaign strategist. Presenting herself as a surrogate for her husband’s populist ideals, she won the Democratic primary and the general election, becoming Texas’s first female governor. She would serve two non-consecutive terms, in 1925–1927 and again in 1933–1935.

This political comeback raised further questions about the effectiveness of constitutional sanctions and the blurred lines between formal eligibility and de facto power. Though legally barred, Ferguson’s continued influence in state politics suggested that impeachment could not always neutralize a popular leader or political movement.

Nonetheless, Ferguson’s removal illustrated the power of the Texas Legislature and the constitutional tools available to it during conflicts with the executive branch. The case is a reminder of the risks of executive overreach and politicizing public institutions.