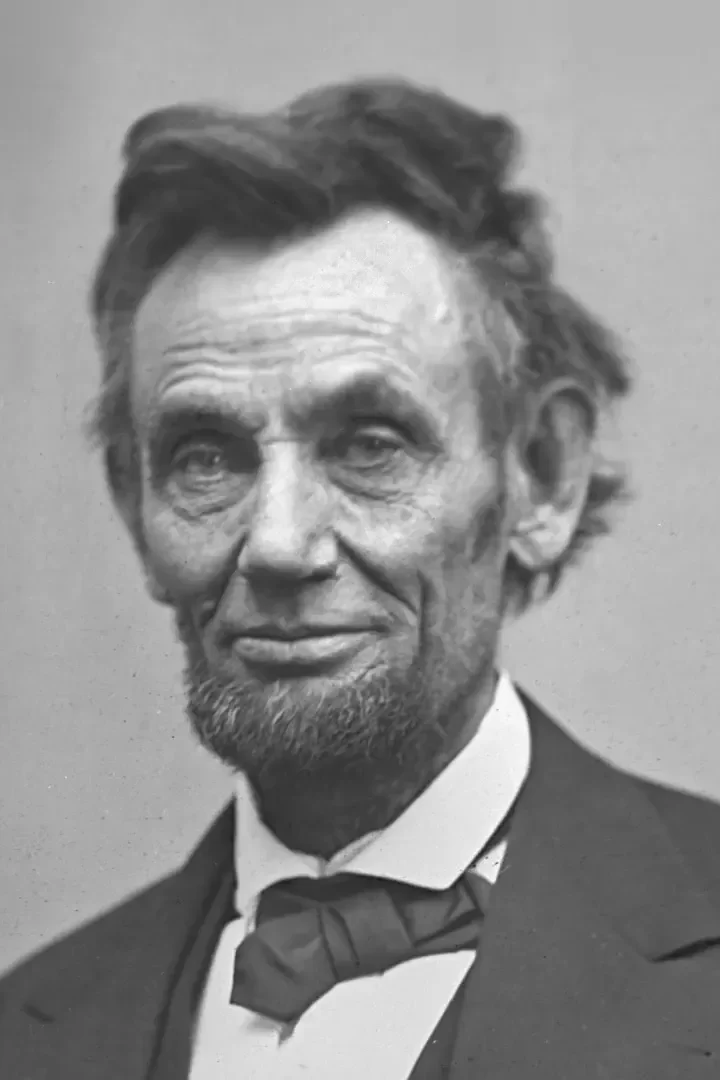

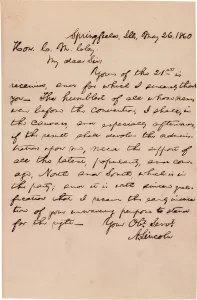

Buried in the archives of the Library of Congress is a forgotten memo in Abraham Lincoln’s own hand—one that outlines a sweeping plan for postwar Texas that might have set the state on a radically different course, had Lincoln not been assassinated in April 1865.

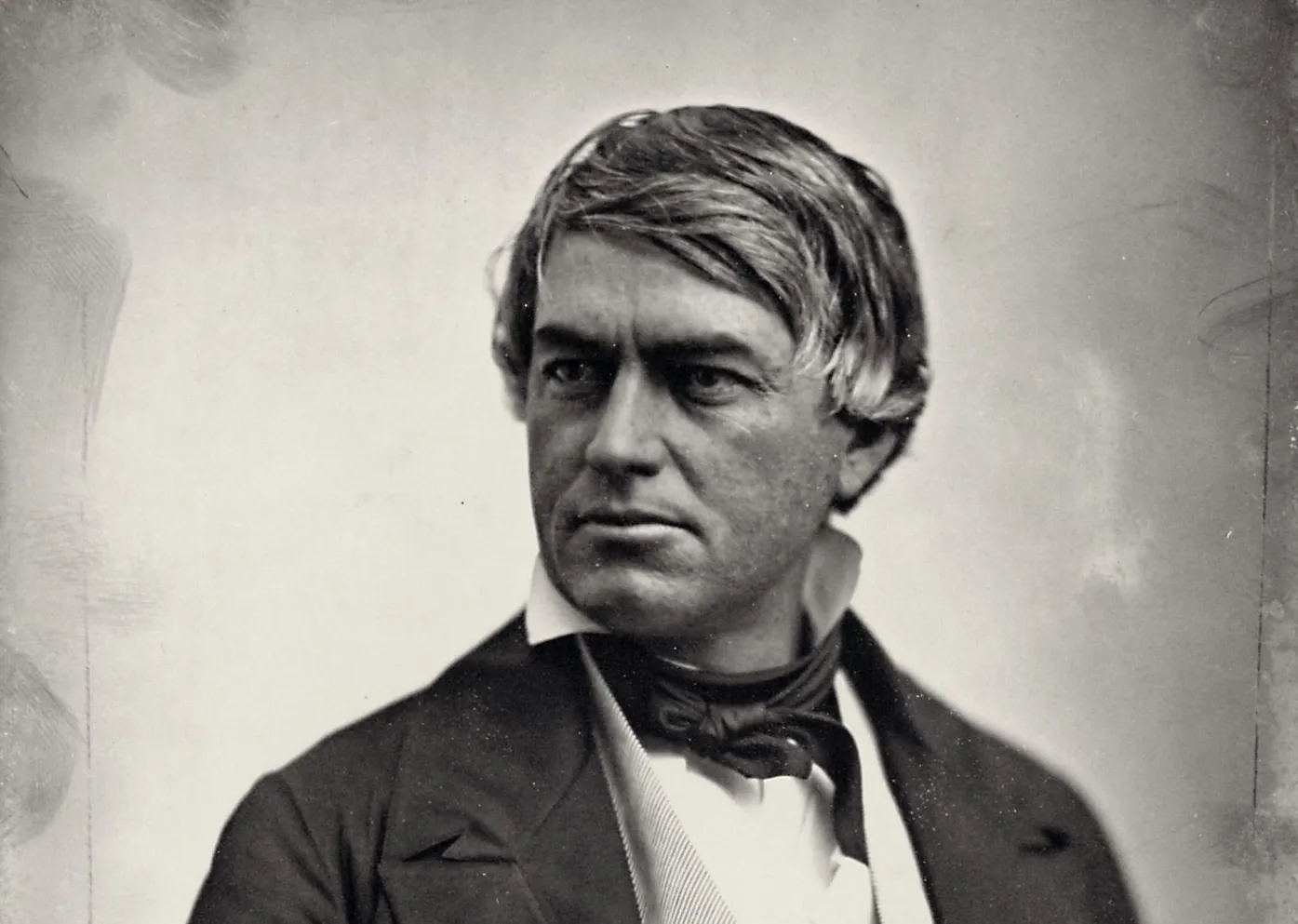

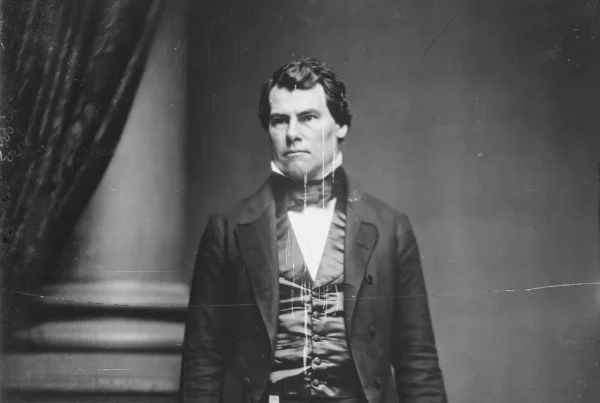

In March 1864, as the Civil War entered its final phases, Lincoln penned a short but striking memo outlining plans “to make Texas a free Union state.” The note, digitized by the Library of Congress but hitherto ignored by historians, was discovered and analyzed by the Texapedia team. It reveals that Lincoln planned to appoint Cassius Marcellus Clay, his ambassador to Russia and a fiery Kentucky abolitionist, to oversee the military occupation of Texas.

Lincoln further contemplated mass land confiscation, a loyalist-led civil government, and the resettlement of New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians en masse to Texas to quell potential resistance, shift the political demographics, and ensure the reintegration of Texas into the Union as a loyal state, cleansed of the social and economic vestiges of slavery.

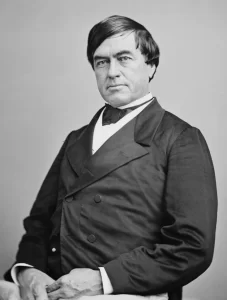

Lincoln’s plan was ambitious, radical, and politically risky. Clay was a veteran of the Mexican-American war, a brawler, dueler, and expert in handling a Bowie knife. Lincoln once remarked that Clay had “a great deal of conceit and very little sense.” Though the two men were political allies, their temperaments could not have been more different. Lincoln was calm, contemplative, and melancholy, whereas Clay was vain, melodramatic, and intemperate.

Lincoln had declined to appoint Clay to his cabinet and had considered—but ultimately rejected—him for a field command in the army. Even so, Lincoln viewed Clay as a man whom he could use to his purposes. In 1862, he dispatched him to Kentucky as his personal political observer to Kentucky, tasked with gauging the potential public reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1863, he sent him back to Russia. And in 1864, as the Civil War entered its cataclysmic final phase, Lincoln looked to the brash, obstinate Kentuckian as just the man to carry out a hardline postwar crackdown in Confederate Texas.

Because Lincoln was killed while Clay was still in Russia, the Kentucky abolitionist likely never learned that the president intended to appoint him to such a prominent post-war position. The memo was written in the privacy of Lincoln’s executive office and subsequently forgotten to history.

Lincoln often used short, undated memoranda like this one to sketch out ideas, test assumptions, or explore possible policies in draft form. The reverse of the page is marked simply: “C. M. Clay, [Military], Texas”—a concise annotation that suggests the memo was filed for reference rather than immediate action. Though it may have been shown to senior aides or members of the cabinet, it likely was never discussed with Clay, who does not mention the matter in his memoirs.

After the war, Clay continued serving as a diplomat, helping to negotiate the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. He never returned to Texas. As a result, the name “Cassius Clay” is virtually unknown in the state—except perhaps among boxing fans, who may recognize it as the birth name of Muhammad Ali. The legendary boxer was named after his father, who in turn was named for the prominent abolitionist.

Had Lincoln’s plan been realized, however, the name Cassius Clay might be far more familiar in Texas today—celebrated by some, perhaps reviled by others. This article examines a lost chapter in Texas history: the story behind Lincoln’s memo, the turbulent political context of the time, and the career of the man who would have headed the first Reconstruction government of Texas.

A Lost Memo from a Critical Moment

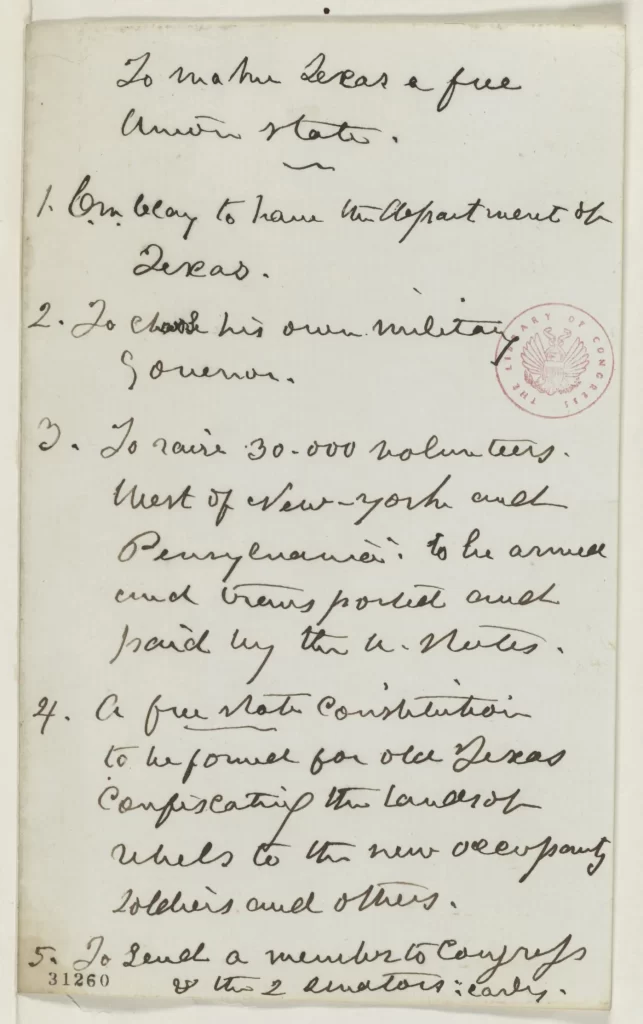

Written on March 4, 1864, Lincoln’s one-page memo consists of five bullet points under the heading “To make Texas a free Union State.” The memo’s first line proposes: “C.M. Clay to have Department of Texas,” referring to Cassius Marcellus Clay. Though Clay’s name is nearly illegible in the memo itself, the handwriting matches Lincoln’s spelling of “C.M. Clay” in other extant correspondence.

In Civil War terminology, a “department” referred to a geographic military command, overseen by a general officer with broad authority over both military operations and wartime civil governance. Thus it appears that Lincoln envisioned appointing Clay as the senior federal authority in Texas—a commanding figure empowered to oversee the transition from Confederate rule to loyal Union statehood.

The second line says, “To choose his own military Governor,” indicating that Clay would have sweeping influence over both military and civil affairs in Texas, though not necessarily direct command of the occupying troops, which would be left to a more professional military man.

The heads of federal military departments in occupied Confederate territories typically were military officers, not civilians, so Lincoln’s memo implies that he intended to grant Clay a temporary military commission. Previously, Lincoln had given Clay a commission as a major-general, but had not given him a field command.

The third point in Lincoln’s memo says, “To raise 30,000 volunteers, [from] west of New York and Pennsylvania; to be armed and transported and paid by the U. States.” The fourth point says, “A free state Constitution to be formed for old Texas—confiscating the lands of rebels to the new occupying soldiers and others.”

Read together, these two points imply plans not just to send occupying soldiers to Texas, but to resettle New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians en masse, with federal backing. Lincoln envisioned a Reconstruction-era constitution for Texas that abolished slavery and redistributed land seized from Confederate sympathizers. The land would go to Union soldiers and loyal settlers, aligning with Radical Republican ideas about punishment and reform.

The fifth point says, “To send a member to Congress & the 2 senators early.” By seating a Congressional delegation, the new government in Texas would help accomplish Lincoln’s plans for restoring a national government that was nationally representative.

For the healing of the nation, Lincoln wanted to ensure that the Southern states sent Congressmen to Washington as soon as possible. This plan differed from that of certain other Republicans, who wanted to punish the Confederate States by excluding them from national political for a long time. For these so-called “Radical Republican,” key goals included purging the South of slavery, punishing it for rebellion, and preventing any Confederate resurgence.

While Lincoln shared these goals, he also wanted to prioritize national unity and healing. By appointing a strong-willed abolitionist to head the military occupation in Texas, he foresaw a difficult struggle for the postwar future of Texas, in which Confederate elites would fight to retain power. To prevent this, he picked a trusted political ally and known firebrand, who was not afraid of a fight, to oversee political developments in the state, with the backing of federal military power.

Lincoln proved to be far-seeing. After his death, the Reconstruction policies of his successors, though forceful at times, failed to prevent former Confederate politicians from returning to power in 1874, inaugurating a century of Jim Crow segregation.

The Man Who Might Have Governed Texas

The man whom Lincoln picked to oversee the military occupation of Texas was a political ally, albeit a volatile and difficult one. Clay and Lincoln were nearly exactly the same age, and they had risen to prominence in the Republican Party at the same time. By some accounts, they were friends.

Although the pair were both Kentucky natives, they were from very different social strata. While Lincoln grew up in poverty, the son of an orphan, Clay belonged to the slave-holding planter class. Despite this, Clay repudiated slavery and became an ardent abolitionist, winning election to the Kentucky legislature three times, and publishing the anti-slavery newspaper True American.

During his career in Kentucky, Clay survived a number of brawls, duels, and assassination attempts His newspaper, which received death threats, was barricaded with iron doors and guarded with two four-pounder cannons. Clay was shot during a political debate in 1843, allegedly by a hired gunman. Fortunately for him, the bullet struck the silver scabbard of his Bowie knife, sparing him. Clay tackled the would-be assassin and slashed at him with his knife, putting out an eye and taking an ear.

For this, he was arrested and tried, but acquitted. Six years later, Clay was attacked by the six sons of a pro-slavery politician. They clubbed him, stabbed him, and fired a gun at his head, but it misfired. Clay fought back, stabbing to death one of the brothers and scattering the others. Though he survived the fight, Clay was so severely wounded that he passed out afterwards.

Clay is rumored to have fought other duels and he was always spoiling for a fight. He joined a company of volunteer cavalry during the Mexican-American War, despite having opposed the recent annexation of Texas, which was admitted to the Union as a slave state.

Clay and his Kentucky volunteers traveled overland through Arkansas and Texas en route to the front. His memoirs recount vividly a bison-hunting expedition that he undertook, ostensibly to provision his troops, among other experiences in Texas. His service in the Mexican-American War thus gave him firsthand, if brief, experience within Texas—a factor that might have influenced Lincoln’s decision.

Clay saw action at the Battle of Buena Vista. He was captured and imprisoned in Mexico, then released at the end of the war.

The Defense of Washington

Clay returned to politics after the war, becoming a founding member of the Republican Party. At the party’s 1860 convention, he was one of several contenders against Lincoln for the presidential nomination, and a runner-up for the vice presidential nomination, which went to Hannibal Hamlin.

Perhaps as a consolation prize, and to maintain unity within the party, Lincoln appointed Clay as his ambassador to Spain. Having coveted a cabinet position, Clay was offended by this. In his memoirs, he wrote, “I went directly to Lincoln and told him I would not accept the mission to an old, effete government like Spain.” He asked instead for a posting to London or Paris. These appointments were taken, so Lincoln offered him instead the ambassadorship to Russia, which Clay accepted.

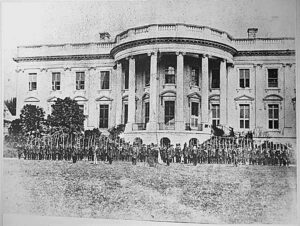

Shortly thereafter, while Clay was still in Washington, the Civil War erupted. The national capital, wedged between the two slave states of Virginia and Maryland, was in peril. Because there were few federal troops in the city at the time, Clay organized a volunteer militia to protect the White House from potential Confederate attack, until federal regiments arrived on the scene.

At the time, Clay was staying at the Willard Hotel, near the White House, with his family. He recalled in his memoirs, “Willard’s was full of guests, from top to bottom, most of them Southerners. There were rumors of the capture of Washington from the beginning… The possession of the capital would have given the South at once the recognition by foreign governments; most of whom were more than willing to see the overthrow of free institutions.”

“That very night I began the enlistment of volunteers for the defense of Washington. The troops of the government were but a fragment of the force necessary to defend the city against traitors in and out of the army; and Col. McGruder, who commanded the largest force, the artillery, was a traitor, and soon went over to the enemy. General Scott, then in command in Washington, was old, and not up to the political fires at work.”

“I occupied a parlor and bedroom, and kept a fine pair of Colt’s revolvers loaded in the latter, whilst I wore my accustomed Bowie knife. As the names of the volunteers were enlisted, I gave the pass-word; and no person whatsoever was entered on the roll whose loyalty was not sustained by our several friends… when the force was sufficient, the companies were organized, and I was made the commander.”

Clay’s boldness and decisiveness in defense of the capital impressed Lincoln, and it put him in the good graces of the War Department and Secretary of State William Seward, who had been cool toward him previously. Thus, before even departing for Moscow, he had put himself in the running for a promotion or a senior military appointment, which is what he desired. In recognition of this service, Lincoln awarded him a Colt revolver, according to Clay’s memoirs.

Wartime Political Service

After helping to secure Washington, Clay departed for St. Petersburg, the capital of Russia at the time. Though he would have preferred to stay statewide to fight the slave-holding Confederates, whom he despised, Clay ultimately ended up playing a crucial diplomatic role in Russia, both before and after the war. Despite his lack of tact, Clay won over the Russian government, which viewed the United States as a potential counterweight to its French and British imperial rivals.

Emperor Alexander II sent warships to U.S. ports in a show of solidarity. This encouraged the U.S. government at the time, and may have helped deter France or Britain from entering the war on the side of the Confederacy.

Lincoln recalled Clay in 1862 and commissioned him a major-general in the army. He soon came to regret this decision. The abolitionist publicly refused to take a field command unless Lincoln agreed to free the slaves in Union-occupied Confederate territories.

Lincoln refused, relegating Clay to a staff position as major-general of volunteers. However, he also found a political use for Clay, sending him to Kentucky to gauge the potential reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation, which he issued in January 1863.

In his memoirs, Clay recalled this exchange with the president in 1862: “Soon Lincoln sent for me, and said, ‘I have been thinking of what you said to me, but I fear if such proclamation of emancipation was made Kentucky would go against us; and we have now as much as we can carry.”

“I replied: ‘You are mistaken… Those who intend to stand by slavery have already joined the rebel army; and those who remain will stand by the Union at all events. Not a man of intelligence will change his ground.’ Lincoln then said: ‘The Kentucky Legislature is now in session. Go down, and see how they stand, and report to me.'”

After accomplishing this mission in Kentucky, Clay lobbied Lincoln for a new assignment. The president wavered, annoyed and uncertain. An anecdote from Senator Orville Browning, who spent an evening with Lincoln on December 12, 1862, reveals Lincolns ambivalent relationship to Clay.

While the senator was with Lincoln, Clay and other gentlemen came calling. Lincoln declined to see them, saying he was engaged. Browning later wrote, “I asked him what he thought of Clay. He answered that he had a great deal of conceit and very little sense, and that he did not know what to do with him, for he could not give him a command—he was not fit for it.”

“He had asked to be permitted to come home from Russia to take part in the war… he consented, and appointed Clay a Major-General…. [but he] was not willing to take a command unless he could control every thing—conduct the war on his own plan, and run the entire machine of Government—That could not be allowed, and he was now urging to be sent back to Russia.”

Clay resigned his military commission on March 11, 1863, and Lincoln sent him back to Russia as ambassador.

Plans to Invade Texas

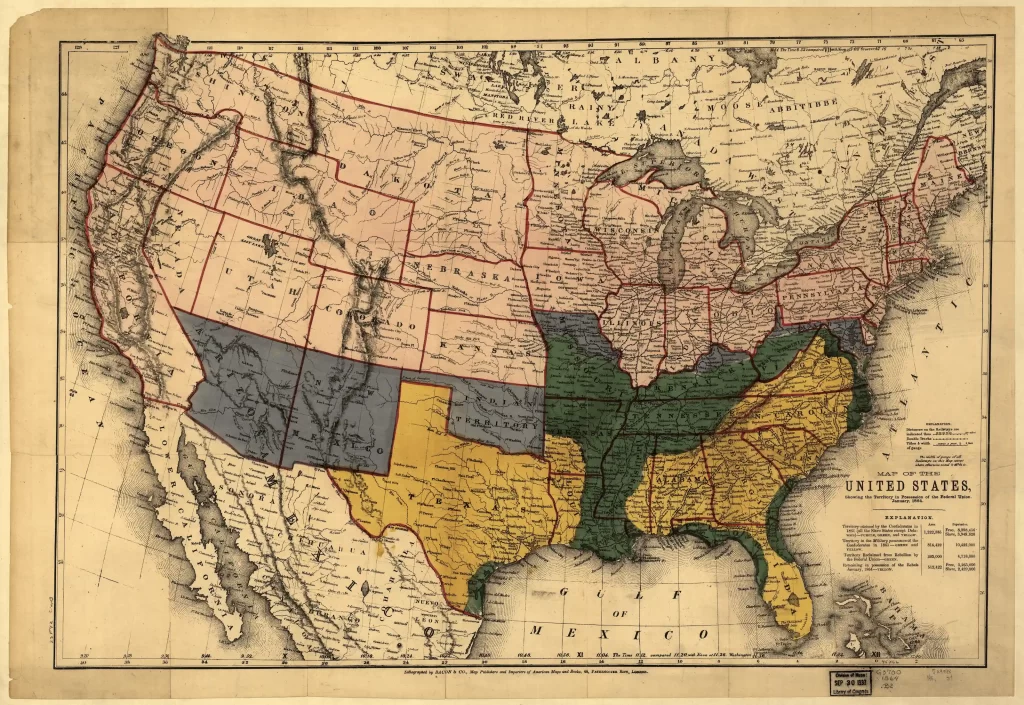

But a year later, Lincoln already was contemplating a new assignment for his volatile ally. His memo outlining plans “to make Texas a free Union state” was written amid preparations for a new Union offensive in Louisiana, which would open the way for an invasion of Texas.

Lincoln, likely aware of the impending campaign, appears to have drafted this memo in anticipation of a Union breakthrough. If successful, Texas would have needed a new administration, to replace the ousted Confederate authorities. It was in this context that he concluded, “C.M. Clay to have Department of Texas.” He planned, evidently, to recall his ambassador from Russia to take on this role.

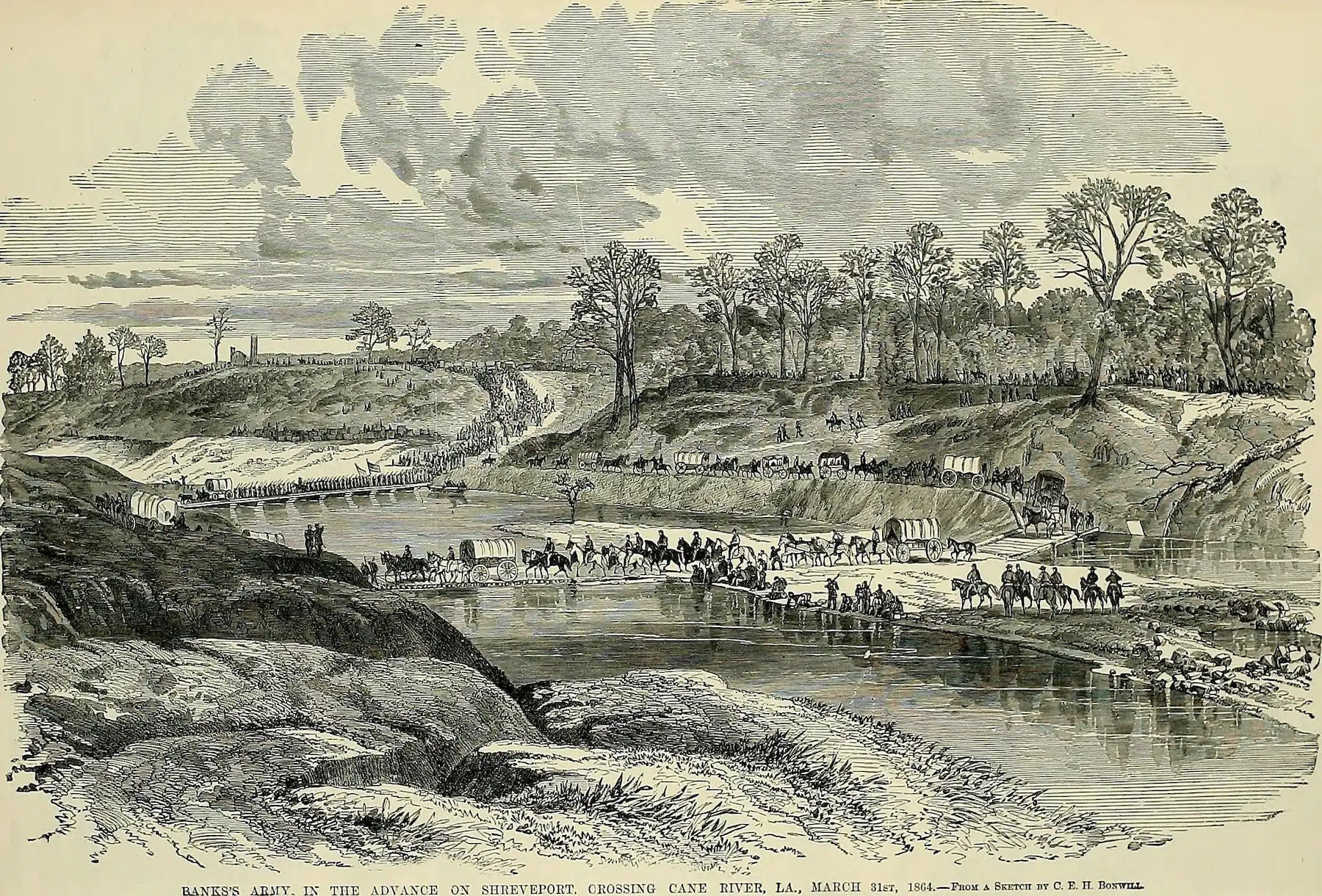

On March 10, 1864, just six days after Lincoln wrote the Clay memo, the Union launched the Red River Campaign, a major joint Army-Navy operation, aiming to capture large parts of Louisiana and push into eastern Texas. The campaign was coordinated by General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant, but its execution was entrusted to three field commanders:

- Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, commander of the Department of the Gulf, led the main Union army column advancing northwest from New Orleans along the Red River.

- Rear Admiral David D. Porter commanded a powerful Union naval flotilla, providing transport, artillery support, and river control along the same route.

- Major General William T. Sherman detached a column under General A.J. Smith from the Army of the Tennessee to move south from Arkansas, converging on Shreveport.

Together, these forces aimed to sweep through western Louisiana, seize Shreveport—the headquarters of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department—and open the path into Texas. But Confederate leaders anticipated the threat. Troops under General Richard Taylor received heavy reinforcements from Confederate forces stationed in Texas, which poured into Louisiana in the weeks before the fighting. Texas units formed a major part of Taylor’s strength, defending the region not only to protect Louisiana but to keep Union forces out of their home state.

The result was a disaster for the Union. On April 8, Banks’s advance was routed at the Battle of Mansfield. The next day’s Battle of Pleasant Hill produced a tactical stalemate. Admiral Porter’s fleet, meanwhile, became stranded upriver by falling water levels and faced constant attack. Union engineers eventually built an emergency dam at Alexandria to allow the flotilla to escape.

Poor coordination, overstretched supply lines, and the sheer size of the theater compounded Union difficulties. By late April, the Red River Campaign had collapsed, and Union forces were retreating. As a result, Texas remained firmly in Confederate hands until the end of the war.

Lincoln was killed on April 14, 1865. Federal troops didn’t occupy Texas until two months later, and his plans for the state never saw the light of day.

Lincoln’s Death and Johnson’s Policies

If Lincoln’s vision had been implemented, Texas history might have followed a dramatically different course. A federally controlled Reconstruction under Clay could have introduced widespread land redistribution, entrenched a civilian government composed of Union loyalists, and re-admitted Texas to the Union under far different terms. Former Confederate leaders might have been disempowered early, and Black civil rights might have been advanced sooner and more securely.

Instead, after Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, President Andrew Johnson pursued a much more lenient course, appointing Andrew J. Hamilton as provisional governor but allowing former Confederates to return to power. Congressional Reconstruction, beginning in 1867, took a firmer stance—requiring a new state constitution and civil rights guarantees—but it never enacted the kind of redistribution or military-led restructuring Lincoln’s memo envisioned.

Historiographical Significance: Rethinking Lincoln’s Reconstruction Vision

This memo may warrant a reevaluation of Lincoln’s views on postwar governance. While Lincoln is often remembered for his relatively lenient “10 Percent Plan” and his emphasis on reconciliation, this document reveals a more assertive, even radical imagination for specific Confederate states. His proposal for Texas included military occupation, property confiscation, and loyalist settlement—measures typically associated with later Radical Republican policies.

The fact that Lincoln drafted such a plan for Texas suggests he was willing to entertain Reconstruction strategies that went beyond voluntary oaths and minimal disruption of the antebellum social order. In this case, he envisioned a clean political break: new leaders, new institutions, and new beneficiaries. It complicates the idea that Lincoln’s approach was uniformly moderate and incremental.

Moreover, the memo demonstrates that Lincoln was planning not just in general terms, but state-by-state. Texas, because of its distance and intact Confederate infrastructure, represented both a challenge and an opportunity. That he assigned such a bold vision to Texas—and to a figure like Cassius Clay—signals that Lincoln may have seen Reconstruction as a flexible project, varying in severity based on local conditions.

The discovery of this memo adds a valuable document to the primary source base for understanding Lincoln’s evolving thinking in 1864. It provides concrete evidence that his vision for Reconstruction could have, under the right conditions, take a more transformative form.