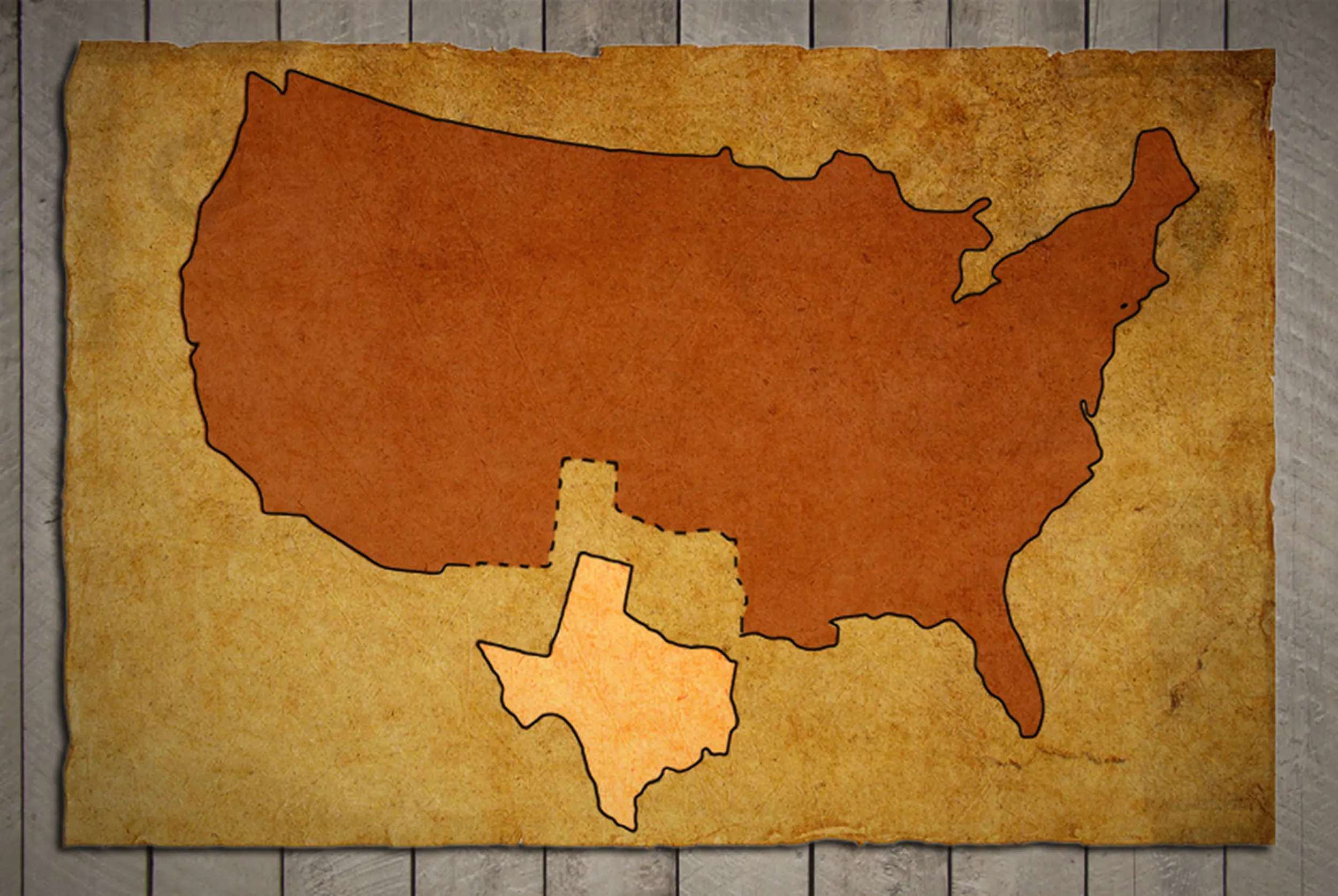

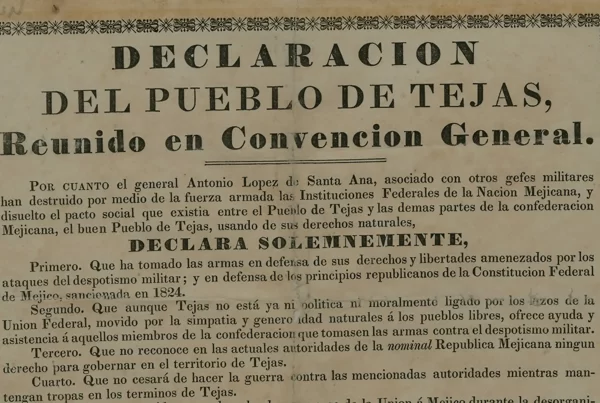

In the fevered months leading up to the Civil War, Texas stood on the threshold of secession. The state had only recently joined the Union in 1845. Now, as Southern states began breaking away in response to Abraham Lincoln’s election, Texans faced a volatile and deeply contested question: Should Texas remain in the Union, or secede and join the Confederacy?

By the time Texans began formally debating secession in January 1861, six states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana—had already voted to leave the Union. These early secessions, all in the Deep South, intensified pressure on Texas to follow suit. Advocates of disunion cited solidarity with neighboring slaveholding states, while opponents warned that the momentum of the movement should not substitute for reasoned judgment.

In the end, Texas voted to secede, and it is remembered as a firmly Confederate state. Yet the decision was anything but unanimous. Political meetings, private arguments, and newspaper editorials reflected a cacophony of viewpoints. One of the most revealing contemporary sources comes from Thomas North, a Northern-born merchant and observer who lived in Texas and Mexico from 1861 to 1866. In his memoir, Five Years in Texas, North identifies five distinct factions that shaped the secession debate.

These factions ranged from hardcore Southern nationalists to quiet Unionists. Their arguments illuminate the tangled loyalties and urgent fears of the moment—and remind us that history, especially in moments of crisis, is never simple.

The Fire-Eaters

North begins with the radicals: those who had favored secession for years, regardless of immediate circumstances. These were the ideological descendants of John C. Calhoun—the so-called nullifiers and hardline Southern nationalists. Though “fewest in numbers,” North notes that this group “embraced in its ranks, most of the talent, wealth, and fashion of the South.” It included the planter elite, such as ex-Governor H.R. Runnels as well as the merchants, professionals, and editors whose fortunes and status were tied to the plantation economy.

This faction, in North’s words, “believed in secession per se, for its own sake,” and had been “plotting and planning for long years to make it an accomplished fact.” To them, Abraham Lincoln’s election was not a threat to be feared, but a long-awaited pretext.

They seized on deep-rooted regional prejudices and cultural resentments—portraying the North as alien, industrial, irreligious, and hostile to the Southern way of life. The Republican Party was cast not just as anti-slavery, but as a vehicle for Northern domination.

“They could now fire the public heart,” North wrote, “through the medium of slavery, and win the prize of Southern independence.” For these men, there was no need to wait for federal encroachment. The moment to break away had arrived.

The Conditional Secessionists

The second group, more numerous than the first, adopted a cautious but ultimately pliable position. They accepted secession only as a last resort, believing that “the rights of the South could not otherwise be preserved inviolate.” As North summarizes their reasoning:

“Wait till the commission of an overt act by the new Administration—Congressional or Executive interference—then will be time enough, and better excuse in the face of the nation and of mankind, for secession.”

This was the rhetoric of conditional loyalty—committed to Southern rights but hesitant to take the plunge. It allowed many Texans to posture as defenders of moderation while still positioning themselves to join the Confederacy when tensions escalated. North saw this faction as more practical than principled, vulnerable to manipulation by the more radical Fire-Eaters.

In practice, when the momentum for secession reached its peak in January 1861, many in this group joined the disunion cause, persuaded that Lincoln’s election or imagined federal interference constituted enough of an “overt act” to justify departure.

The Southern Unionists

A third faction believed that Southern rights could be protected without destroying the Union. North writes:

“A third party believed in preserving the Union at almost all hazards; even with the loss of the peculiar rights of the South. They argued and urged that Southern rights could be maintained by fighting for them, if need be, ‘in the Union and under the old flag.’ This party was quite numerous.”

This group included conservatives, old Whigs, and many who had served in the U.S. military or held federal office. They viewed the Constitution as a strong enough framework to resolve disputes without bloodshed. Their stance was loyalist but not necessarily abolitionist.

To North, their voices were pragmatic but ultimately drowned out. They lacked the fervor of the secessionists and failed to command the same emotional response from the public. Their defense of the Union was rooted in precedent and principle—but not in firebrand rhetoric. As events moved rapidly toward disunion, this group was unable to prevent the tide.

The Reluctant Emancipationists

The fourth group, though small, held the most morally striking position—one that North viewed with some sympathy.

“A fourth party said, but dare not say it very loud, ‘Let slavery slide, if need be—it is not worth shedding blood over, but let us have the Union. Besides, the sentiment of all mankind is against our servile system, and history will dig its grave at last.’ This party was in the minority of all.”

This quote captures the marginalized position of anti-slavery sentiment in Texas. North characterizes it as “weak, maudlin, and mawkish anti-slaveryism,” present “here and there, through the South; but it had no bowels of effective demonstration; no inherent potency of melting mercy and just indignation, to stem the counter current.”

Still, these quiet dissidents offered a prophetic voice. They recognized that slavery’s time was limited—and that war to preserve it was a tragic miscalculation. Many of these men and women would later support emancipation or quietly resist Confederate authority.

The Anti-Secessionists

The final faction North describes consisted of those who opposed secession on grounds of policy, prudence, and survival. They were not abolitionists, nor were they driven by love for the North. Rather, they saw secession as a self-defeating course that would bring devastation to the South. Their most prominent voice was General Sam Houston, the sitting Governor of Texas and former president of the Republic.

North explains their reasoning in blunt and memorable terms:

“Still a fifth party opposed secession under any circumstances, on the ground of bad policy, and inexpediency. They said, secession is suicide, the very course to pursue by which to swamp and lose our rights. Secession will be a stupendous failure, and we shall lose by it the very thing we propose thereby to defend and save.”

Houston’s message was clear and consistent: disunion meant war. The North, with its superior industry, population, and infrastructure, would not allow the Union to be dismembered without a fight. He predicted that the Confederacy would be isolated diplomatically, crushed militarily, and impoverished economically. What’s more, he believed that secession would give rise to internal tyranny—an unaccountable wartime government that would trample liberty in the name of preserving it.

This wasn’t merely rhetoric. Houston had years of experience in both state and national politics, and he had no illusions about the strength of the federal government. He warned that secession would break down trade, invite military occupation, and end in defeat and humiliation.

In North’s account, this faction was in the minority but far from insignificant. It included “large and respectable masses of the people” who preferred Union to disunion, even if they disliked the direction of national politics. Their stance reflected not moral awakening but calculated foresight.

Ultimately, however, these warnings went unheeded. Texas held a referendum in February 1861, and a clear majority voted for secession. Houston refused to swear loyalty to the Confederacy and was removed from office shortly after. He retired from public life, deeply grieved by what he saw as a tragic mistake.

The war that followed would validate much of what he and his allies had predicted. Texas, though spared many major battles, suffered deeply from blockade, inflation, conscription, internal dissent, and postwar occupation. As North wrote with some vindication, “Prophetic words, which subsequent events literally fulfilled.”

What Followed

Texas officially seceded from the Union on March 2, 1861. The disunionists prevailed. In the years that followed, the United States was engulfed in a civil war that claimed over 750,000 lives—the bloodiest conflict in American history. While Texas saw fewer battles than states east of the Mississippi, its people did not escape the toll. Thousands of Texans were killed in battle or died from disease. Families were separated, communities fractured, and supply lines strained to the breaking point.

The Union naval blockade strangled the Texas coastline, cutting off trade and contributing to widespread shortages of food, medicine, and manufactured goods. Prices soared. Confederate currency collapsed.

Enslaved people fled plantations in growing numbers, and White families who had once considered themselves secure were plunged into uncertainty. Desertion rates increased as the war dragged on and morale faltered. Internal dissent—particularly among Unionist pockets in German settlements and the Hill Country—led to vigilante violence, arrests, and executions.

By 1865, Texas was defeated alongside the rest of the Confederacy. The enslaved population was emancipated by military order and the Thirteenth Amendment, though freedom brought with it few protections and immense hardship. Union troops occupied key parts of the state for years to come. Political power shifted abruptly, and the former ruling class was temporarily disenfranchised. Reconstruction would bring its own turmoil, as new struggles emerged over rights, power, and memory.

The path chosen in 1861 led not to independence or glory, but to death, destruction, and lasting upheaval. The warnings offered by the few who counseled restraint—men like Sam Houston—had not been enough to change the course of events. Yet if the war hadn’t happened, slavery might have persisted in Texas for generations longer.

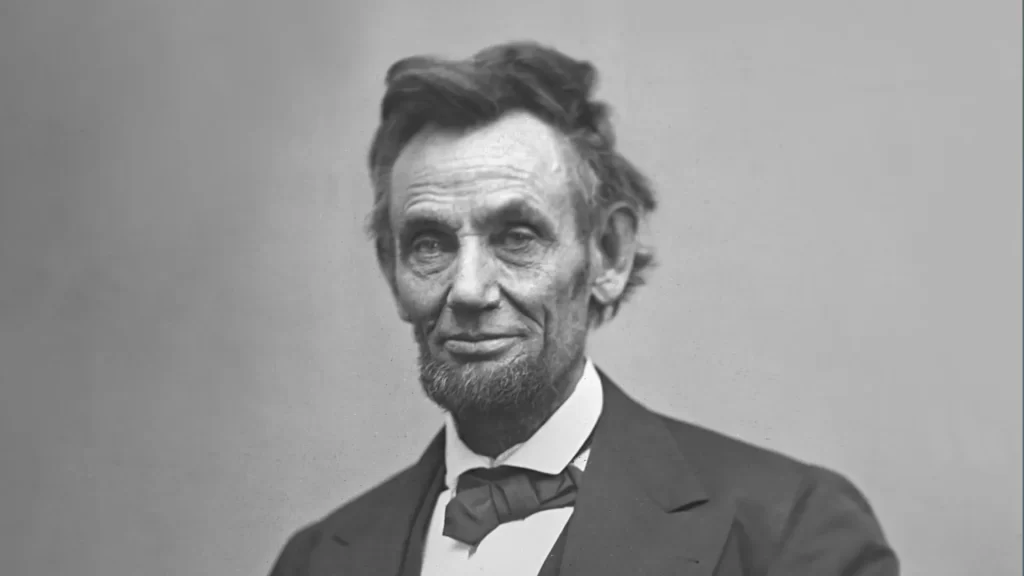

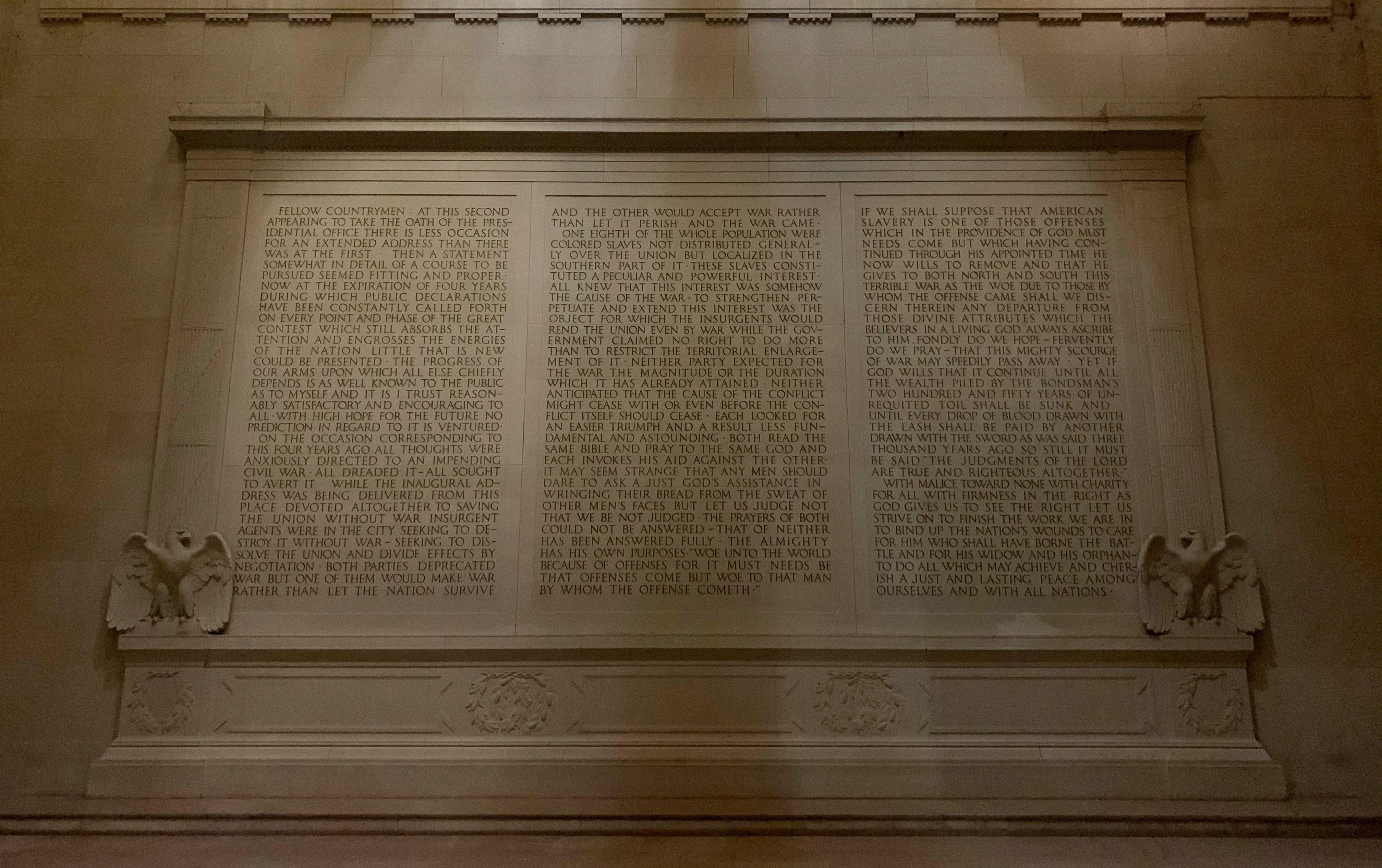

Some Americans, including President Lincoln, came to see the war itself as a kind of divine reckoning—a national punishment for the sin of slavery. He expressed this view with solemn clarity in his Second Inaugural Address, delivered on March 4, 1865, as the war neared its end:

“Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained… Each looked for an [easy] triumph… Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God and each invokes His aid against the other… The prayers of both could not be answered—that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. ‘Woe unto the world because of offenses for it must needs be that offenses come but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.'”

“If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses, which in the providence of God must needs come, but which having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?”

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago; so, still it must be said,

‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.'”

The secessionists had won the argument in 1861. But by 1865, the war they had unleashed had consumed everything they claimed to defend. And even Lincoln, who despised slavery, celebrated the Union’s victory with grieving and humility—and declared the war to have been a punishment that scarred every corner of the nation, even as it brought emancipation.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War

- A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy

- Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848-1865

- Colossal Ambitions: Confederate Planning for a Post–Civil War World

- The Texas Lowcountry: Slavery and Freedom on the Gulf Coast, 1822–1895

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.